The High Priestess of Soul at Her Height

1) There should be a Nobel Prize for music, embracing all genres; 2) If there were, Nina Simone would certainly have been a contender

A decade or so ago, in the mid-2010s, there was a resurgence of interest in the singer/pianist/songwriter Nina Simone, who died, aged 70, in 2003. I took note of this mini-renaissance, but was too tied up at the time to investigate the causes of this renewed flurry of interest in a great artist.

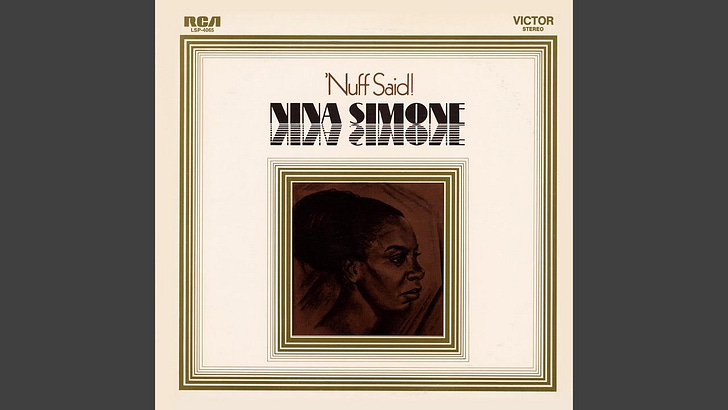

I did, however, enjoy frequent chats about Miss Simone with her younger brother, Sam Waymon, a gifted musician himself who lived for years in my hometown of Nyack, NY. Sam often collaborated with Nina, playing organ, for instance, on her 1968 album ‘Nuff Said, from which I’ve selected four of the eight small masterpieces that I am posting below, and will try to write intelligently about.

Eunice Waymon was born in 1933, the sixth of eight children in a poor family in Tryon, NC. She showed an early gift, if not genius, for the piano. Bach became a major, longtime presence in her musical life. With the help of hometown supporters, Eunice spent the summer of 1950 at New York’s Juilliard School, preparing for an audition to study at another prestigious school, the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where all students received full scholarships. The circumstances of the audition are unclear. Eunice was rejected. Discussing the episode with Sam, I asked him if racism had played a role in his sister’s rejection. Sam gave me a look. “Of course it did,” he said. The truth may not be that simple. Curtis had accepted Black piano students before. We don’t know why Eunice Waymon was rejected.

Whether out of disappointment at her failed audition or not, Miss Waymon switched her performing focus to jazz and pop, though she continued to study classical music on her own. In 1954, she chose the pseudonym “Nina Simone,” and started playing in bars and clubs. She had a breakthrough hit in 1959 with her rendition of the Gershwins’ “I Loves You Porgy,” sending it to #18 on Billboard’s Hot 100.

By the mid-1960s, Simone was an ardent civil rights activist, writing 1964’s “Mississippi Goddam” and 1969’s “To Be Young, Gifted and Black.” “Mississippi Goddam,” prompted largely by the murder of Medgar Evers, was, Simone said, “my first civil rights song,” which came to her “in a rush of fury, hatred and determination.” Writing the song, she said, “was like throwing ten bullets back at them,” ie. at white racists. In 1967, Simone released a very different, sweet-tempered civil rights song, “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free.” Years later, looking back on the mid-to-late Sixties, Simone said, “I felt more alive then than I feel now because I was needed, and I could sing something to help my people.” 1

In the late ‘60s, Simone altered her style again, generously incorporating the day’s rock, soul, and R&B into her repertoire: electric guitar and bass, electronic keyboards, drums high up in the mix. These were Nina Simone’s rock & soul years. Which is where I, essentially a rock guy, came in. I have two favorite Nina albums, ‘Nuff Said (1968) and To Love Somebody (1969). All but one of the songs below come from these two records.

Most of ‘Nuff Said was recorded at Long Island’s Westbury Music Fair on April 7, 1968, three days after the murder of Martin Luther King, an event which generated the moving soliloquy that Simone delivers at the beginning of ‘Nuff Said’s Sunday-goin’-to-meetin’ song “Sunday in Savannah.” Perhaps improbably (taste is mysterious),

Simone was a big fan of the Bee Gees, whose songs she often covered. The Gibb brothers’ “In the Morning” (originally titled “Morning of My Life”), “To Love Somebody,” “I Can’t See Nobody” and “Please Read Me” are all on either ‘Nuff Said or To Love Somebody. ‘Nuff Said opens with Simone’s reading of the obscure, off-puttingly wimpy (in the Bee Gees’ hands) “In the Morning.” It is my favorite Nina Simone song.

‘Nuff Said sounds live (all but the final track, “Do What You Gotta Do”), but it’s only partially so. A bit of detective work reveals that three of its 11 tracks—“In the Morning,” “Ain’t Got No (I Got Life”) and “Do What You Gotta Do”—were recorded not at the Westbury Music Fair, but at RCA Studios in Manhattan on May 13, 1968, more than a month after the Westbury show. The applause for “In the Morning” and “Ain’t Got No (I Got Life”), as well as the emcee’s opening greeting— “Ladies and gentlemen, the Westbury Music Fair takes great pride in presenting the High Priestess of Soul, Miss Nina Simone”—were similarly recorded at RCA Studios. For some reason, “Do What You Gotta Do,” also recorded at RCA Studios, has no canned applause. It’s allowed to stand naked, a studio recording tacked onto a “live” album. Why was ‘Nuff Said recorded half-live and half in the studio? Because artist and band screwed three songs up so badly that they couldn’t be mended with a few edits—"fixed in the mix,” as they say—but had to be completely re-recorded? That’s my guess. To my mind, moreover, “Do What You Gotta Do,” by the hit-making songwriter Jimmy Webb, was never part of the Westbury concert, but was recorded purely as an afterthought and tacked onto the end of the album. Why no dubbed applause? I have no idea. All I can say is that it’s amazing that ‘Nuff Said holds up under such a major cutting-and-pasting job. Actually, it doesn’t truly hold up. ‘Nuff Said sounds like a live album that ends, incongruously, with a studio-recorded song, “Do What You Gotta Do.”

From the mid-’60s through the ‘90s, Simone had a number of hit albums on Billboard’s R&B and jazz charts. ‘Nuff Said was a minor-to-mid-level R&B hit, reaching #44 on Billboard’s R&B chart, and a pop hit in Britain, where it climbed to #11. Simone never had a pop hit album in the USA. 1965’s Pastel Blues, which went all the way to #8 on Billboard’s R&B chart, made it only as far as #139 on the Top 200, Billboard’s all-important pop chart. She made her living on the road and from other artists’ covers of her compositions.

“Ain’t Got No (I Got Life)” is another song that I will never get tired of hearing; it’s ‘Nuff Said at its most infectious. Simone concocted it out of two songs, “Ain’t Got No” and “I Got Life,” from the trailblazing hippie musical Hair, which made it to Broadway in April, 1968 and ran for 1,750 performances. In a 2016 paper, the Yale musicologist Daphne Brooks hails Simone’s “Ain’t Got No (I Got Life)” as “a new black anthem,” a “wholly original” reimagining of the Hair medley (it’s not a medley in the musical; it’s two entirely different songs, with four songs intervening) “to create a ‘trademark’ racial protest song as powerful as Simone’s earlier ‘Mississippi Goddam.’” What bullshit! “Ain’t Got No (I Got Life)” is Simone’s own paean to the pleasure of owning, if nothing else, one’s own hair, head, brain, eyes, ears, boobs (Simone inserted “boobs” herself) heart, soul, and the rest of our natural birthright. If you’re a 21st-century Yale theorist who wants to read Simone’s medley as an ode to Blackness, go right ahead. You’re talking jive.

“Sunday in Savannah” was cut live, at Westbury, on April 7, 1968—three days, that is, after Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated. Hence Simone’s moving spoken tribute to King, in which she never mentions him by name, and which carries her into the song proper at 1:50. “We’re glad to see you,” she says, “and happily surprised to see so many of you. We really didn’t expect anybody tonight, and you know why.” In fact, a Nina Simone show was a better place to gather in the wake of such a gruesome, tragic incident, and to receive comfort from a great-souled woman, than just about anywhere else.

“Sunday in Savannah” is, on the face of it, a simple song about black communities not merely in Savannah, GA, but across the nation, the parson “hollering in the righteous way.” The song concludes with Simone offering one of the most powerful, protracted “Amen”s [5:28-5:42] that I’ve ever heard. I’ve listened to “Sunday in Savannah” many dozens, if not hundreds, of times since Simone recorded it in that terrible spring of 1968. I recall listening to it during a high-school lunch period in 1968. I’m listening to it now, with unalloyed pleasure.

Looking to cash in on ‘Nuff Said’s modest success, Simone’s label, RCA, packed To Love Somebody with covers of songs by big-name rock and folk-rock artists (see two paragraphs down). They should have realized that the innately idiosyncratic Ms. Simone was hit-resistant.

On To Love Somebody’s title song, Simone took the Gibbs’ second American single (the first was “New York Mining Disaster 1941”) and turned it into rock-solid rock & roll. She had help—joining Simone’s piano in the rhythm section were the top-tier bassist Chuck Rainey and guitarist Eric Gale and, most notably, Bernard Purdie, one of the great funk drummers of all time, and one of the pop music’s most-recorded drummers. Purdie propels the song mightily, taking the listener on a muscular, ultra-funky ride. RCA was paying a lot of money for session hands of this caliber—and the album failed to chart.

Regardless of her hitproof eccentricity, I think that Simone entertained hopes of making it as a rock star. For one thing, there are all of those big pop hits she covered on album after ‘60s and ‘70s album (I haven’t mentioned one-third of them. She covered Hall and Oates’s “Rich Girl”! She covered Melanie’s “What Have They Done to My Song, Ma”!) For another, consider To Love Somebody’s album-jacket illustration. Against an Eden-like backdrop of meadow and trees, a seraphic young white couple, wearing not a whole lot of clothes, gaze into each other’s eyes as if they’re about to fall into each other’s arms. The album cover is aimed straight at that big white market; it has zero to do with Nina Simone, avatar of Black Power. Unless RCA’s executives insisted on the cover over Simone’s objections, one suspects that she was eager indeed to reach the young white market. There’s also the album’s plentiful helping of songs by white countercultural heroes: the Bee Gees (apart from “To Love Somebody,” Simone sings their “I Can’t See Nobody”); Dylan (represented by “I Shall Be Released,” “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” and “The Times They Are a-Changing”); Leonard Cohen (“Suzanne”), and the Byrds (“Turn, Turn, Turn”). In any case, this whitebread album jacket is wholly atypical of Simone’s post-1965 album covers, which generally clothed her in turbans, dashikis, and other Afro-garb.

Simone was an ardent interpreter of Bob Dylan, especially on this album. She shifts her version of this, one of the Bard’s greatest songs, into 3/4 time, which, along with her chitlin’-style piano, gives her “I Shall Be Released” a bluesier feel than any of the many versions that exist, recorded by Dylan and others. Harmonically, “I Shall Be Released” is as simple as virtually every Dylan song. It’s just four chords, I-ii-IV-V (same as Dylan’s “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere”), into which Simone inserts a minor 6th for soulfulness’s sake. She sings “I Shall Be Released” with a stoic bluesiness (you know that her heart’s breaking underneath that impassive sung/spoken delivery), and play a great piano accompaniment, filled with casually flicked-off right-hand flourishes (1:32-1:33). Unlike the matter-of-fact delivery, the coda, wherein an impassioned Simone takes 17 seconds (3:33-3:50) to sing/shout/holler the final word— “released”—is straight out of church, as impassioned as her closing “Amen” on “Sunday in Savannah.” If someone were to ask Dylan for his favorite rendering of “I Shall Be Released,” I wouldn’t be at all surprised if he named this one. (Same goes for the song coming up, another Dylan tune she turns inside-out.)

In her version of “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues,” which Dylan recorded on Highway 61 Revisited (1965), Simone locates the core of heartbreak that Dylan hid with his acerbicity. Simone’s version is sung by a sorrowing, exhausted witness to Dylan’s account of a string of absurd, opaque, and troubling events. Among other small but significant touches, she puts an interesting, racially inflected spin on Dylan’s lyric “Up on housing-project hill, it’s either fortune or fame.” Dylan was a white fellow who called a housing project “a housing project.” To a Black like Simone, a housing project was a plain “project,” thus Simone’s “Up on project hill, it’s either fortune or fame.” The tiny difference speaks racial volumes. Another touch: Dylan takes his song out with his usual sardonic, complaining whine. Simone has been more deeply troubled, and wounded, by the song’s events. Before starting the final verse, she improvises a remark that bespeaks her exhaustion: “Well, that’s it, folks. That’s it” [3:53-3:56], and limps into one of Dylan’s most depressing verses (see footnote2 ). Dylan’s version of “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” is sung by an embittered, disgusted, but still energetic individual. Simone’s is a tale told by an exhausted, strung-out inhabitant of Desolation Row.

As I said above, I suspect that “Do What You Gotta Do,” which was recorded in the studio, more than a month after the concert that produced most of ‘Nuff Said, was not part of the original plan for the album, but an afterthought, tacked on as the album’s final song. It’s much more than filler; it’s a first-class, much-covered song by the hit-making songwriter Jimmy Webb. The scenario: the spurned lover, her broken heart notwithstanding, has the caritas to do what so few heartbroken rejectees find it in themselves to do: tell the departing beloved not to feel guilty, not to listen to the community that condemns his heartlessness, but to “Do what you gotta do/ My wild sweet love/Though it may mean I'll never kiss your sweet lips again/ Pay that no mind/Just find that dappled dream of yours/ Come on back and see me when you can.” Of course one doesn’t often come across such noble sentiments. But Simone makes the song believable. Lots of artists have covered “Do What You’ve Gotta Do”: Roberta Flack, Linda Ronstadt, Clarence Carter, the Four Tops. Simone’s version is the least bathetic, the bravest. It’s definitive.

This is the only song I’ve chosen that doesn’t come from ‘Nuff Said or To Love Somebody. I’ll give myself a pass—it is one of the iconic songs of Simone’s career. It was written primarily by the jazz pianist Billy Taylor (he had some help with the lyrics), who released his version in 1963. Simone’s is on the album Silk and Soul (above), which she released in 1966. “I Wish I Knew How….” was covered by countless artists, but it’s safe to say that it was in Simone’s hands that the song became a civil-rights anthem (although, typically for Simone, her version didn’t chart). I would bet, moreover, that it was Nina Simone’s version that The New York Times had in mind when it named the song “one of the greatest songs of the sixties.”

Bernard Purdie and Eric Gale are here on drums and guitar, ensuring that Simone has the solidest possible foundation, although in this case the mighty Purdie reins himself in appropriately, only switching from brushes to drumsticks when the song starts to build in passion and volume. As I recall, I haven’t heard any of the many covers of the song (I’ve heard Billy Taylor’s, which doesn’t come close to Simone’s). The artists who’ve sung the song include Solomon Burke, Junior Mance, Mary Travers of Peter, Paul and Mary (?!), John Denver (?!), Mavis Staples, and the Blind Boys of Alabama. Without listening to any of these, I feel pretty secure in betting that Simone’s is definitive. To Taylor’s credit, the song has all the right ingredients for an anthem; all it needed, and finally got, was the right artist to put it across.

So we’re ending this dive into my two favorite Nina Simone albums on a positive note, with Simone’s uplifting version of an iconic song. Nina Simone’s life ended on a far from positive note. But this piece is about her great music, not her troubled life.

Aretha Franklin recorded Simone’s “To Be Young Gifted and Black” on Franklin’s 1972 album Young, Gifted and Black, which Aretha sent to #2 on Billboard’s R&B albums chart and #11 on Billboard’s Top 200. Aretha’s version, produced by a mighty triumvirate—the Atlantic Records executives Jerry Wexler, Arif Mardin, and Tom Dowd—is a little overblown, especially compared to Simone’s minimalist version.

Dylan’s famously desolate final verse to “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”:

"Well, I started out on burgundy, but soon hit the harder stuff

Everybody said they’d stand behind me when the game got rough

But the joke was on me, there was nobody even there to bluff

I'm going back to New York City, I do believe I've had enough.”

Fyi, except for "To Love Somebody"'s bizarre "Revolution"s. They're not the Beatles', but sort of an answer to them. John Lennon liked them; he was probably flattered. They detract from this must-have album

For a while now I've been thinking about what Nina Simone records to buy. Thanks for the recommendations--just ordered both!