RY COODER IN FOUR EPISODES, 1985-2023 Episode 3, Part 1: "I Found the Answer. It was in "Buena Vista."

"If I had a nickel for every time someone came up to me and said, "Buena Vista Social Club" changed my life...."

Cooder and I had gone our separate ways by the time we reconnected in 2008 for a four-hour, 10,000-word interview, “Ry, Flathead,” originally published in the March 2009 issue of Stopsmiling, another now-defunct magazine. Our marathon conversation, which took place over two days, has been edited for length and clarity and divided into two parts. The first, right here, is the story of a single, epochal adventure; the second, which I will post later this week, ranges across the artist’s entire life.

“Amor de Loca Juventud,” one of the finest tracks from the surprise blockbuster album of the 1990s. The singers are Compay Segundo and Julio Fernandez. Ry Cooder plays a typically understated slide guitar solo from 1:30 to 2:20.

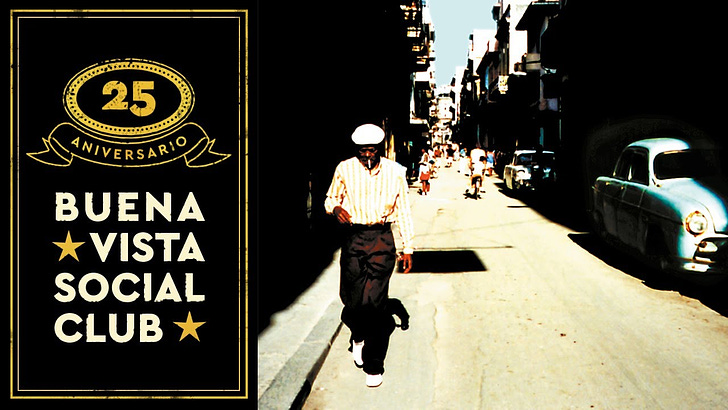

The cover photograph, shot by the photographer Susan Titelman, Cooder’s wife, shows Ibrahim Ferrer, an almost entirely forgotten singer whose career had peaked in the 1950s and ‘60s, about to enter the studio for his first session. It quietly captures a compelling moment: a long-silent singer about to find out if he’s still got it. Ferrer turned out to be one of Buena Vista Social Club’s most charming, affecting performers. He went on to make two solo albums, one of which, Buenos Hermanos, won a Grammy in 2004. Ferrer died the following year.

WHEN WE TALKED IN THE EIGHTIES, YOU were not a happy man.

Well, life got better. I didn’t like having a solo career at all. It was the wrong fit. And if you’re doing things you know are wrong for you, then you’re liable to be discouraged and disgruntled.

But I found the answer, and it was while making Buena Vista Social Club. Namely, do something for other people and you’ll do something for yourself. Once that was revealed to me, everything got better. I mean it really did.

I hadn’t realized the record sold eight million copies.

You bet your ass. If I didn’t have a piece of that record. I don’t know what I’d be doing now, because I didn’t have a nickel. And I didn’t have any particular prospects. And that started to sink in. And [the album’s de facto co-producer] Nick Gold — you could say the same about him. He and I just flat stumbled onto this thing.

What made it so popular?

The media really did. Because if you have good music—I mean really good, beautiful—then the public will respond. But the media has to be your partner, which it was in this case.

Because it was such a good story.

Right. The story sold it across. And there was an expansionist mood in this country, which the war in Iraq shut down. There was this moment, this opening, in the mid-to-late Nineties, and the media said, “We’ll take a little time with this. It’s charming.” They wouldn’t do that now. As Walter Hill used to say, “If you’re out of your time slot, you might as well drink up and go home.”

“Something happened in that room,” you’ve said about Buena Vista,“and I still haven’t figured out exactly what it was.”

Well, Egrem Studios, this ancient, state-owned studio, was wonderful, like an old radio studio with a high ceiling and a beautiful sound. With this kind of acoustic music, in this kind of room, you’re recording the air, you’re recording the room. I got in a big argument with the engineer, getting him to back the mikes off, to let the air move. It took us three days to dial that sound. Hardly anybody goes to that trouble anymore; nowadays they cut the damn album in three days.

So what happened was, rather than business as usual, get the money and go home, the musicians didn’t want to go home. The playback sounded so good, they wanted to keep playing. If you get a good playback you’ll want to hear another one, and another. Jim Keltner calls it “the call of the playback.”1 [Guitarist and tres player] Compay Segundo was eighty-nine, the session’s elder statesman. He grew up before there were records and hadn’t heard the world through speakers, like we do. He went, “Aha. Aha. Bueno. I pronounce this to be worthwhile. Hoho, I’ll stay.” [Pianist] Rubén González couldn’t be pried from the piano. Rubén recorded on that piano in the Sixties. Same instrument. Damn thing hadn’t moved.

So where the players sit, how to place the mikes, you have to figure that shit out, and as I say, most people never take the time, they’re just thinking about the clock and the dollars. But Nick’s not that kind of guy. He could see we were onto something and he said, “Let’s try to do this right. Let’s do the best we can and maybe we’ll get something.”

Another thing Nick did that sets him apart in my book is that once the record took off, he went back down to Cuba with cash and paid every heir to every songwriter he could find. And I’m talking hefty five figures per. So Nick got known around the island as the man who came with the money. If some third nephew was the only heir, he got the money.

When we had started recording and the word was out, people lined up outside of Egrem and around the block. “I play the cowbell.” “I play the bumper guard, don’t you want to hear me?” “I wrote a song.” “I wrote ten thousand songs.” We had stations. If somebody got past the foyer into the room, the inner sanctum, it was because they actually had something going.

Who were the Buena Vista musicians who had the biggest impact on you?

It usually seems to be the oldest ones, the ones that are closest to the origins. Compay Segundo was the one you’d want to hang with, the one with the most knowledge and who can actually demonstrate it. I’d play something and Compay would go, “Incorrecto! Incorrecto!” Take the guitar away from me and play.

I’d say, “That’s what I was playing!”

He’d look at me. “A-ha.” He had this phrase in Spanish. “My word is the seal of quality.” This is a guy who lived secure in the knowledge that he knew exactly what it was all about. He’d made dozens of records, but that’s not what counted. It was the thing he had inside himself. I’ve always said that Gabby Pahinui and Joseph Spence [the former a Hawaiian slack-key guitarist, the latter a Bahamian fingerstyle guitar master, both long dead] were my two biggest influences. And Compay Segundo and Joseph Spence, they’re practically the same person. I recognized it in Compay’s hand motions. “Oh, that’s Spence.”

Ry Cooder studying the fretwork of 89-year-old Compay Segundo, the elder statesman of the Buena Vista Social Club ensemble. By the end of the sessions, Cooder had all but admitted Segundo into his select pantheon of guitar icons. “This is a guy,” said Cooder, “who lived secure in the knowledge that he knew exactly what it was all about.”

Most musicians just listen to the record or watch the video. You actually seek these people out.

You need to experience these guys in the flesh. You need to sit with them, absorb what they do as directly as possible, not second-hand through records, films, books. So you look for an entry and go through it. But you have to have an idea—you can’t just go knock on Lalo Guerrero’s door and say, “Hi! Here I am!” You learn you’d better have a goddamn plan. [The guitarist and singer Lalo Guerrero, known as “the father of Chicano music,” who played a significant role in Cooder’s 2005 album Chávez Ravine.]

Buena Vista Social Club’s fifteen-plus-member ensemble of septuagenarians and older was too creaky and unwieldy to tour. The group, in which Cooder and his percussionist son, Joachim, played inconspicuous but key roles, gave three concerts, in 1998, two in Amsterdam and a triumphant appearance at Carnegie Hall. The Carnegie show was recorded but not released until 2008. It was, however, filmed by Wim Wenders, who also shot lots of footage in and around Havana. Wenders’s Oscar-nominated documentary Buena Vista Social Club was released in 1999. (The Buena Vista album won 1997’s Best Tropical Latin Performance Grammy—a parochial category, one might say, for an album with a global impact.)

Aside from the obvious result of ending your financial troubles, did the album’s commercial success make things any easier for you?

What it meant for a time, a very short time, was that people returned phone calls. I’d get an idea and put a call through to so-and-so, and by God, I’d get called back. When Buena Vista was hot, people in the record business liked to take my calls. “Hey! Blah blah blah!” Not that it made any difference, because there was nothing they could or would do for me. You’re in fashion for a minute.

Where it helped the most was that musicians I wanted to work with, like Lalo Guerrero, now had trust. Now my reputation preceded me. They see you coming and say, “He’s solid. Oh, yes, Buena Vista. Very fine! Let us talk.” That trust made it possible to do Chávez Ravine. Everybody knew I was all right, that I didn’t mean any harm. Because white people are not particularly trusted or liked.

If you’re talking about the public’s response, most people don’t know my earlier records. But they damn sure—and by “they” I mean everybody, Croatians, Brazilians—know that goddamn record and that film. Buena Vista cut across all borders. I’m telling you, if I had a nickel for every time someone came up to me and said, “Buena Vista Social Club changed my life….” There should’ve been a bumper sticker.

Like you and I agreed, it was the story that affected people. Everybody told me the same thing: “When Ibrahim Ferrer looks up at the sky on Fifth Avenue, I’m there with him.” People took Ibrahim to heart to such an extent that when they saw him they would weep. I had it happen in a grocery store in Brentwood, an affluent neighborhood where we go grocery shopping. Ibrahim was with me. We get to the checkout line and this woman turns around, wealthy Brentwood lady, and bursts into tears! She goddamn near fainted! I thought I was going to have to give her smelling salts, for Christ’s sake, right in the line at Vicente Foods!

That’s when you know you’ve got something. It’s not like saying, “Ohhh, I love you” to Warren Beatty or “Your new marriage is just so much better for you.” None of that. It’s real. I’m telling you, it’s from the heart.

They knew Ibrahim had been shining shoes for a living.

They knew that he was some real cat and that he had this in him, to be this open-hearted cat who could take them with him.

The standing ovation at the end of the Carnegie Hall show must have been a pretty moving moment for you. You knew what this must have meant to the musicians.

Oh yeah, of course. It was, “Okay, we’ve brought this all the way to this point.” Here was this audience that was going mad, and here’s these musicians being given a glimpse of the world. Not that I’m so crazy about the world, but let’s show them that we care about them, provide an experience that’s meaningful for them, that they enjoy, doing something they love to do. I could have done the same for [the Tennessee blues musician] Sleepy John Estes. It’s a matter of opportunity. This was a great thing to have the opportunity to do. And for once the audience got it. Finally! I’ve been doing this a long time, you know. To see the audience—that being the world—get something for the right reasons, rather than the wrong fucking reasons, is pretty gratifying. You can say, “All right, then.” You knew this could happen, you just didn’t expect it to. It was moving, all right.

“OK, we’ve brought this all the way to this point. It was moving, all right.” Standing ovation at Carnegie Hall, July 1998.

The brilliant drummer Jim Keltner played on almost all of Ry Cooder’s records between 1970 and 1990 and a number thereafter, as well as for literally hundreds of other artists. One could confidently call Keltner one of the half-dozen best, most prolific recording session drummers of the 1970s, ‘80s, ‘90s, and well into the 2000s.

I was a Cooderite from Into The Purple Valley, so when Buena Vista and A Meeting By The River and Talking Timbuktu came out, I just simply embraced them, and had my mind blown. I went to Havana in 2008 just to hear music. I saw almost all of the Buena Vista stars in Denver and Boulder.