Robbie Robertson: A Hawk Flies South, Chapter 2 of 4: "Southbound"

A rock icon tells the story, in four chapters, of how a 1950s street punk from Toronto turned himself into a guitar genius and master songwriter. Here's Chapter Two, "Southbound."

The man who taught Robbie Robertson how to rock and roll never achieved anything like Robbie’s success. None of Ronnie Hawkins’s singles or albums made the Top 10, or Top 20, on America’s pop charts; his highest-charting single, “Mary Lou,” made it only as far as #26 in 1959. Paradoxically, it was in Canada that this son of the South achieved the popularity that eluded him in the USA.

Hawkins was born in Huntsville, Arkansas in 1935 and raised in nearby Fayetteville. His mother was a teacher. “But his father…. Jasper Newton Hawkins was no teacher. He was a barber. A dangerous barber. He was a drunk. He nearly cut somebody’s ear off one time. There was all these Jasper Newton stories.”

Ronnie Hawkins was a first-generation rock & roller, raised on rockabilly, the blend of country and rhythm & blues that lit the whole world ablaze in the mid-to-late 1950s: the sound of the young Elvis, of Ronnie Hawkins’s own cousin Dale, who hit big with “Suzie Q”; of Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, Eddie Cochran, and Harold Jenkins, who changed his name to Conway Twitty and ditched rockabilly for country. No sooner had Ronnie heard that they were crazy about rockabilly up in Canada than he was northward bound. Ronnie Hawkins and his Hawks did well, very well, in Ontario, scoring plenty of hit singles and albums. Ronnie opened his own club, the Hawk’s Nest, on Yonge Street, the heart of Toronto’s party district, and hosted rock & roll and rhythm & blues’s biggest names.

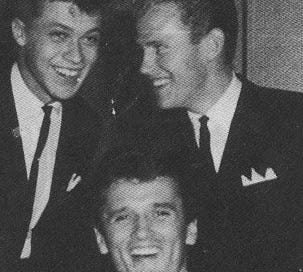

Say cheese, everybody. A teenaged Robbie Robertson and his Hawks bandmate Levon Helm stand behind their boss, Ronnie Hawkins.

Robbie wails on his Fender Telecaster as a goateed Ronnie Hawkins (trying on the day’s beatnik look) looks on approvingly. “My job was to make this work,” says Robbie. People thought Hawkins was crazy to hire an untested 16-year-old as his lead guitarist, and Robbie’s mission was to prove them wrong.

Ronnie could croon a folky Gordon Lighfoot ballad with the best of them (his third album was titled Folk Ballads of Ronnie Hawkins), but was most comfortable creating mayhem, a rockabilly tummler whose moves included back flips, leaps into the audience, and his camel walk, a progenitor of Michael Jackson’s moonwalk. “When the Hawk took the stage,” writes Robertson in Testimony, “you could taste something raw and authentic in the air. It was the most violent, dynamic, primitive rock ‘n’ roll I had ever witnessed, and it was addictive.” Holding everything together, says Robbie, “was a young beam of light on drums”: Levon Helm, who was to play a major, perhaps the major, role in Robbie’s life for the next fifteen years.1

Robbie shadowed Hawkins, making himself useful whenever possible, anything to get the boss’s attention, at which he succeeded. After several of the Hawks announced their intentions to move on, Ronnie let Robbie know that he was on the short list of candidates for lead guitarist.

Soon enough, Hawkins phoned Robbie from his Fayetteville home base and instructed the kid to buy a one-way train ticket south. “I was to meet them in Fayetteville,” says Robbie, “and then we were going to go down to West Helena2 and that’s where they were going to start breaking me in.

“This was ‘We’ll see how it works out.’ Once I got down there, that’s when I went on a mission. There was no chance, as far as I was concerned, that Ronnie was going to say, ‘Well, son, we tried, but it isn’t going to work out.’ That was not going to happen.”

The region surrounding, and especially south of, West Helena—the Mississippi Delta, that is, from Memphis down to southern Mississippi—had long been Robbie’s Oz, his Mecca: the land where not merely the blues, but rock & roll itself, were born. Riding the southbound train, the kid could hardly contain himself.

“This was the first time I’d ever been truly far from home. Driving on this train, and going through all these states, and getting closer to this place… this was almost, to me at my young age, a religious experience. When I got off in Fayetteville and smelled the air, I thought, ‘Mmm mmm.’ It was kind of sweet. And it was just right for me.

“Then we went down the mountains and through Little Rock to southern Arkansas, where Levon was from. And here I finally was, at the source.” The air in the Delta was no longer sweet, but dense, heavy. “The air was….still. And everything was extremely foreign to me. I remember Levon saying, ‘In this part of the country there are eight black people to one white.’ Here was a place where you could hear music coming out of the night. I’d hear things and I didn’t know whether it was a far-off harmonica, or some kind of animal, or a train—I didn’t know what the hell it was. But it sounded like music.

“And West Helena was such a reservoir of phrases, and talk, and rhythms, and characters, and faces, and all these stories. I didn’t know if they were true or not, but they were flying at you.” Robbie was all but transfixed. “All I can tell you is, you take a guy who is already obsessed, music has already taken over all the senses of their body, and you put them at sixteen years old at a place in the Mississippi Delta, and that is what it does. When I went down there, it didn’t let me down a bit.”

“Mojo Man,” from the 1961 album of the same name, Robbie Robertson on lead guitar

Levon’s given name was “Lavonne,” which was objectionably effeminate to him, so he changed it. His father’s name was Diamond and his mother’s name was Nell but everyone called her Shuck. Levon was born in Elaine, Arkansas and raised in Turkey Scratch, just outside of Marvell. These tiny communities were tucked into the northwest corner of the Mississippi Delta, suburbs, as it were, of the slightly less tiny municipalities of Helena and West Helena.

A charismatic figure even at 19, Levon was multitalented. He was to become one of the finest, most influential drummers in ‘60s and ‘70s rock; he sang with an unforgettable twangy growl, and his mandolin is all over the Band’s records. Three years older than Robbie, Levon was the kid’s best friend and big brother, his moral, sexual, and musical compass, though I’ll note that from the mid-1970s on, an enmity developed between Helm and Robertson that Robbie always insisted was solely on Levon’s part. From shortly after “The Last Waltz” concert in 1976 to his final days in 2012, Levon refused to speak to Robbie, who continued to insist that he bore his old friend no ill will. He said this plainly to me, on the several occasions we spoke in the mid-1990s. Put simply, Levon resented what he considered Robertson’s refusal to share songwriting credits. But Levon’s hostility ran deeper than that, and needs to be explored, at greater length, elsewhere.

Helena and West Helena consolidated in 2006 into plain Helena. In the 1950s, West Helena especially was a major musical community, home to several clubs that played important roles in the evolution of rockabilly. One of West Helena’s town fathers was Charlie Halbert, whom Robbie calls “a sort of patron of the rockabilly arts.” Halbert owned the Delta Supper Club, which regularly hosted rockabilly’s biggest names; the Delta Queen, which ferried passengers across the big river from Helena to Clarksdale, Mississippi, and the Rainbow Court Motel, whose well-furnished bungalows were ideal rehearsal spaces for visiting bands.

In the first audio segment, below, Robbie recalls his southbound journey. The second is Robbie’s account of a later event, which we’ll title “Bo Diddley Comes to Call.” Robbie was staying at the Warwick Hotel in Toronto (even though his mom lived in town, he liked to stick with the band). Bo Diddley was playing a nearby club, and Ronnie suggested that Robbie invite the great man to the Warwick for a sociable hang. When Robbie approached him, Bo said, “Yeah, I’ll come by. What room you in?” As it happened, Robbie had also invited “to our post-show get-together” a demure young thing he’d met that night (who turned out to be a high-schooler with borrowed ID) The more the merrier, n'est ce pas? What happened next was, well, listen for yourself.