Robbie Robertson: A Hawk Flies South, Chapter 1 of 4: "Enter Jaime Royal Robertson"

The story, in four chapters, of how a 1950s Toronto street punk took the first steps on his road to rock & roll mastery. Here's Chapter One.

INTRODUCTION

Robbie Robertson died in August 2023, but not before leaving an outsized mark on the world of rock & roll. Between 1968 (Music from Big Pink) and 1976 (The Last Waltz), Robertson was the chief songwriter, sole guitarist, and, towards the end, de facto leader of arguably America’s most influential rock group, the Band. In an eight-hour interview conducted here, there, and everywhere during the autumn of 1991, I managed to penetrate the smokescreen behind which Robertson preferred to operate, the wall he had long before erected between the world and himself.

I chose to explore a portion of Robertson’s life about which even less was known than about his years with the Band, and to which, for that reason, I was especially drawn. In the mid-1950s, the music that had only recently welled up in America’s deep South, chiefly the city of Memphis, hurtled northwards, capturing the imagination of a teenager in Toronto and literally pulling him south, apprenticed for a half-dozen years, from age 16 to age 22, to the wild-eyed rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins, who ruled his crack backup band, the Hawks, with an iron hand. Ronnie Hawkins, barely older than his musicians but far more worldly-wise—“Son,” he told Robertson when he hired him, “you won’t make much money but you’ll get more pussy than Frank Sinatra”— worked the bucket-of-blood circuit—clubs, frat parties, and the occasional concert—that ran in those days from the Mississippi Delta to Ontario.

I chose to tell the story in Robbie’s words, a first-person narrative shaped from that massive interview. Once Robbie realized that I was up to something potentially interesting, he drew back the curtain, as it were, and could not have been more generous with his time nor willing to wrack his brain for decades-old memories (he was 47 when we met). The story appeared in the December 1991 issue of Musician. It was enthusiastically received, and had legs. In 1997, the critic Greil Marcus wrote, “Robertson has often spoken of writing his own book, and the very long interview he did with Tony Scherman, published as “Youngblood: The Wild Youth of Robbie Robertson,” the [memories] of a born raconteur, all blood, sweat, and booze, gives the best sense of how rich a book that might be.”

As pleased as I was that so eminent a literary figure liked my story, I was a little ticked off by Marcus’s reference to my slaved-over narrative as an “interview.” My role, as I saw it, was more along the lines of a documentary filmmaker than that of a mere interviewer, the highly creative task that lay ahead of me to shape hours of raw footage into a story as compelling as I could make it. Most of what Robbie told me remained on the cutting-room floor. Nor does it appear in the memoir that he did get around to writing, Testimony. But it appears here.

“A Hawk Flies South” starts with Robbie’s tangled prehistory and ends on the eve of Bob Dylan’s entry into Robertson’s life. As in all four chapters, choice portions of our interview appear below, in the original audio.

Chapter 1: Enter Jaime Royal Robertson

In 1991, Robbie Robertson had yet to speak at length about his Native American identity. His mother, born Rosemarie Myke in 1922, was Mohawk and Cayuga, raised on the Six Nations Indian Reserve, seventy-five miles south of Toronto. In 1922, being Native was, as Robbie put it, “not cool.” The school that Rosemarie, whom her family called Dolly, attended at Six Nations was similar in intent to the famous, now infamous Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, to which the great athlete Jim Thorpe, a member of the Sac and Fox Nation, was brought for indoctrination.1 In the Six Nations school, as at Carlisle, students, or inductees, were forbidden to speak their native language or, as Robbie writes, “to practice any of your bloodline traditions. From an early age, I remember y mother and her relations quietly passing around the phrase ‘Be proud you are an Indian, but be careful who you tell.’” Dolly’s son followed her example for years.

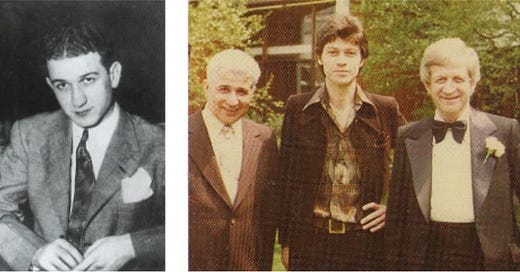

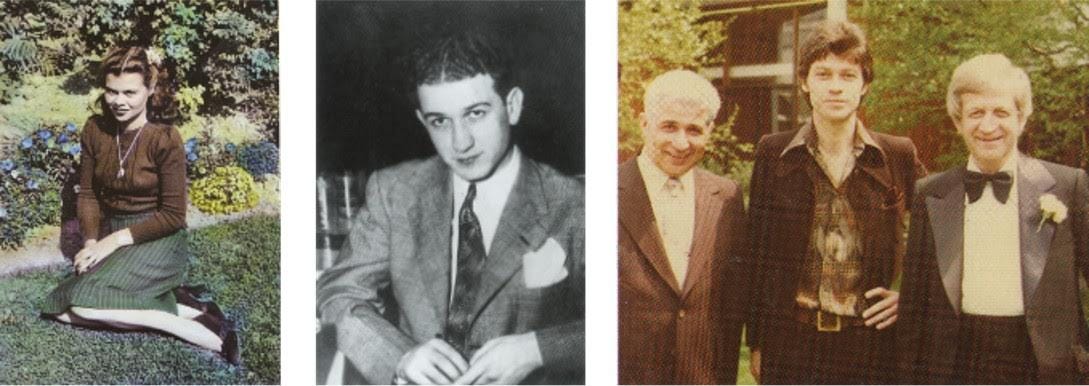

Left: “Dolly”: Rosemarie Myke Robertson, mid-1940s

Middle: Alex Klegerman, ca. 1940-42

Bottom: A young Robbie Robertson with his Klegerman uncles, Morrie and Natie, date unk.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Among the Musical to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.