Paul Simon on Almost Everything, Chapter 4 of 5: "Graceland: 1984-1992"

"'Graceland,' says Paul Simon, "the song and the album, is probably the best thing I ever did."

Roy Halee, Paul Simon’s engineer, co-producer and close collaborator, was confident that the depression that had descended on Simon with the simultaneous failure of his marriage to Carrie Fisher and his album Hearts and Bones would not last. “Paul was the most competitive person I’ve ever known,” said Halee. “I knew he’d give me a call someday, and we’d be heading back into the studio.”

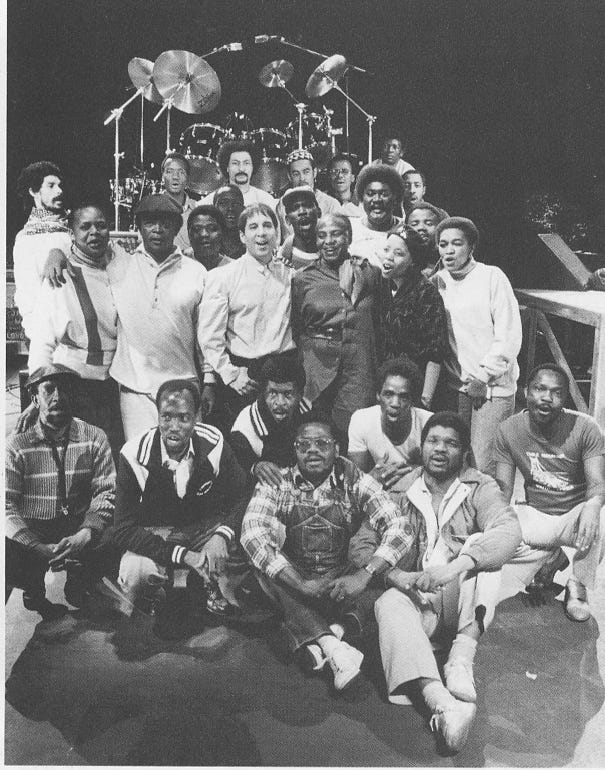

The Graceland world tour getting set to hit the road, January 1987. The closest the troupe could get to South Africa was neighboring Zimbabwe: South Africa’s apartheid laws prohibited Blacks and whites from performing together or attending public events together.

In the spring of 1984, a singer/songwriter named Heidi Berg played Simon several of her songs, which appealed to him. He might be interested, he said, in producing her album, and asked her to bring in some recordings that reflected the sound she was looking for. Among them was a tape called Gumboots: Accordion Jive hits, Volume II, which a South African friend of Berg’s had sent her.

Simon was entranced; this music, which he hadn’t known existed, magically evoked genres he’d loved as a boy and still loved, including the 1950s doo-wop and R & B of

Graceland as yet unreleased and the tour yet to begin, Ladysmith Black Mambazo and Simon give America a taste of what was to come, performing the album’s “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” on (Simon’s) home turf, Saturday Night Live, May 1986

the Cadillacs, the Del-Vikings and Clyde McPhatter’s Drifters, as well as the Sun Records that Sam Phillips had cut in mid-’50s Memphis on Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, and Carl Perkins. Simon’s creative fires were stoked. He asked the South African record producer Hilton Rosenthal to find the musicians on the tape, and others, too, and began making plans to visit and, he hoped, to record in South Africa: one of the world’s most racist countries, where Blacks were ruthlessly subjugated.

Simon was well aware that both the United Nations and the African National Congress, South Africa’s anti-apartheid political party-in-exile, had levied a boycott forbidding musicians from performing in that country. But politics were not uppermost in Simon’s mind. What was, was going to South Africa’s biggest city, Johannesburg, where the best musicians were, and cutting an album with them. He bumped into Heidi Berg in August, 1984 and excitedly told her of his plans. She was anything but pleased. “I loaned him the tape because I wanted to make a record,” she said. “I didn’t loan him the tape so he would make a record.”

It was unclear whether the boycott extended to recording. Simon asked the singer and activist Harry Belafonte and the composer/arranger Quincy Jones, Simon’s longtime friend and sometime collaborator, for advice. Both were encouraging, although Belafonte suggested that Simon consult the ANC. Simon didn’t take the advice. He didn’t believe that musicians needed politicians’ permission to make music (this is his vociferously repeated argument on the second audio segment below). The South African Black musicians’ union passed a resolution formally inviting Simon to record, although some of the country’s Black musicians regarded Simon’s adventure with suspicion. What did he want and what was he prepared to give, and would working with him get them in trouble? Regardless, Simon and Halee boarded a plane for Johannesburg in February 1985, anxious and excited.

Not all of the musicians whom Rosenthal spoke to knew who Paul Simon was. “I mostly listened to township music,” said the superbly gifted bassist Bakithi Kumalo. When Rosenthal contacted him, Kumalo said, ‘Who is Paul Simon?’ Rosenthal sang a few bars of “Mother and Child Reunion.” “Oh, so that’s Paul Simon,” said Kumalo. “But why would someone that famous want to record with me? I was only playing music part-time. My regular job was working as a mechanic in a garage. But there was no way I could let the opportunity pass.” Still, Kumalo was skeptical, wondering “Who is going to want to hear this township music in America?”1

When Simon and Halee arrived in Johannesburg, they were met by Rosenthal and a group of musicians whom Simon would discover were indeed top-notch. The Americans were further delighted to find that Johannesburg’s Ovation Recording Studio was state-of-the-art. A rhythm section quickly formed around Kumalo, the drummer Isaac Mtshali, and the guitarist Chikapa “Ray” Phiri, musicians of skill and imagination. Simon was unable to connect with the dozen-member a capella choir Ladysmith Black Mambazo, whose intricate, buoyant harmonies thrilled him—“Paul was so engrossed by the group’s singing,” writes Simon’s biographer, Robert Hilburn, “that he listened to Ladysmith tapes over and over at night, sometimes falling asleep to them.” Simon finally hooked up with Ladysmith’s leader, the Zulu singer/composer/arranger Joseph Shabalala, who agreed to co-compose a song long-distance and take it from there. Graceland would be unimaginable without Ladysmith’s contributions: “Homeless,” “You Can Call Me Al,” and “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes.”

Over the course of the Johannesburg sessions, “everything came together,” Kumalo recalled, “and we were like this big family.” Apartheid made its presence felt regardless. Blacks were not permitted on Johannesburg’s streets or buses after 5 p.m., and as the day wore on, the musicians grew visibly anxious. The townships were on the obscure outskirts of Johannesburg, and Simon often had to arrange rides home. In the middle of what he called the “euphoric” feeling in the studio, “you would have reminders that you’re living in an incredibly tense racial environment, where the law of the land was apartheid.”

After two-and-a-half weeks, Simon flew home with the instrumental tracks to six songs: “Graceland,” “The Boy in the Bubble,” “You Can Call Me Al,” “I Know What I Know,” “Gumboots,” and “Crazy Love, Vol. II.” He hadn’t written any lyrics, because his method of songwriting had of late undergone a radical overhaul.

Previously, Simon had composed like every other songwriter: words and music came more or less at the same time, mutually shaping each other, and the finished song was put to tape. But now Simon wanted the words to emerge from the music. His new modus operandi was to listen, over and over, to the finished instrumental track, and to began singing whatever words and phrases the music triggered. This was songwriting sans pen and paper. Rather, pen and paper became involved after a phrase or a verse was lodged in Simon’s mind. Most likely to be rewritten. Over and over.

The account that Simon gave Robert Hilburn of how “Graceland,” the song, took shape, a process that started in Johannesburg and ended at Simon’s house in Montauk, Long Island, is an invaluable, blow-by-blow narrative of how Paul Simon worked circa 1985 and in decades to come.

On that first day at Ovation, Vusi Khumalo improvised a drum part “that sounded like a country rockabilly shuffle,” Simon recalled, “which is something I’ve loved since I was a kid.” When Ray Phiri showed up on the second day, Simon played the drum track for him, “and he starts to play something that has a sort of rockabilly feel, even though Ray doesn’t know Sun Records or rockabilly. He does, however, know American country music, at least vaguely. And it sounded good with the drums.” Phiri was playing in the key of E, going back and forth between E and A in a nice, bouncy groove. Then “he plays a C-sharp minor, which surprised me because South African music doesn’t usually have minor chords. I asked him why he played the relative minor,” said Simon (C-sharp minor is the minor sixth, or relative minor, in the key of E), “and he said because he had listened to my records, and I used it all the time. So I realize that Ray is taking information from American country music and my music and integrating it with South African music. That’s why I say the track is a mixture of the two musical worlds; not something that was an intellectual decision, but an organic experience.”

Simon sat, or paced, at home, listening to that first track, and the phrase “I’m going to Graceland, Graceland” popped into his head. He had no idea why. And, frustratingly, he couldn’t come up with anything beyond those five words.

“He spent hours,” Hilburn writes, “in his bedroom listening to the track and going over the phrase ‘I’m going to Graceland, Graceland.’ His first thought was, ‘That doesn’t work. I’m not writing a song about Elvis Presley in an album of South African music.’ But the line stuck with me, and after a couple of months, I decide I ought to go to Graceland, since I’d never been there.” After recording the zydeco track that became the song ‘That Was Your Mother’ in Crowley, Louisiana, “I rent a car and drive to Memphis.2 While I’m driving through Mississippi, I’m suddenly singing The Misissippi Delta was shining like a bottleneck guitar/I am following the river/Down the highway/Through the cradle of the Civil War/I’m going to Graceland, Graceland/In Memphis, Tennessee.” (“Bottleneck” would be replaced by “National”: a National guitar, or dobro, with its silvery, metallic body.)

“I loved it immediately. For one thing, I loved to put the words ‘Memphis, Tennessee’ in a song. It goes all the way back to first hearing Chuck Berry sing it [in Berry’s song of that name] in the Fifties. The line about ‘Poor boys and pilgrims with families’ came up because I never called Graceland in advance to get a guided tour or anything. I just bought my ticket and sat in the waiting room with everyone else until the bus came and we all went up to Elvis’s house.

“Now I’m back in Montauk and I start writing about the journey, and I come up with a story about a traveling companion who is nine years old, who is the child of my first wife. That’s my son Harper, though he wasn’t really on the trip with me. It was just storytelling. But I still don’t know where the song is going. But when I get to I’ve reason to believe/We both will be received/In Graceland, I think, ‘That’s interesting, the spiritual connotation of it.’ The word ‘Graceland’ became a metaphor for the album.

“The next line—She comes back to tell me she’s gone—is half-funny, but it’s also heartbreaking, about how hard it is to break up. It’s as if she’s telling me something I don’t know, as if I didn’t know my own bed. Now the song is starting to take shape. This is a search for something, and there’s been a breakup. That was me and Carrie. And then we got to the lines about Losing love is like a window in your heart/Everybody sees you’re blown apart.

“When that came out, I thought someone had punched me in the heart. I lost my breath. I just sat down. At the same time, the part of my brain that is the songwriter thinks, ‘That’s good.’

“I thought that was the end of the song. But then, as I was walking past the Museum of Natural History in Manhattan, the line There’s a girl in New York City/Who calls herself the human trampoline came to me. She really has no place in the song, but it’s interesting. What does it mean, bouncing into Graceland? Then I think maybe we are all bouncing into Graceland. Eventually I understood that the song is about why we are traveling to Graceland—to find out how to get healed—and that’s why I named the album Graceland. It seemed to be about finding something that you could call a state of grace—the healing of a deep wound. And that’s what was going on in South Africa. There was a deep wound, and then an attempt at a healing process.”3

It took hundreds of hours for Simon to come up with the lyrics to “Graceland,” using his new method, “stream of consciousness, edited” (see Chapter 3, interview segment #1), an approach that could take a long time. For instance, it took Simon from July 3, 1985 until September 22 to write the lyrics to Graceland’s opening song, “The Boy in the Bubble.” Cutting the instrumental tracks was a breeze by comparison.

The final song to be recorded—the high-energy “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes,” written by Joseph Shabalala and Simon—was cut during Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s May 1986 trip to New York, when the group appeared with Simon on Saturday Night Live. “Everyone”—cast, audience, crew—”was in awe” of the performance, said SNL’s producer, Lorne Michaels. “It wasn’t like anything that was on the show before. You could feel the excitement in the studio.”

The album was released in late August, 1986, largely to critical huzzahs. The Village Voice’s jaundiced music editor, Robert Christgau, wrote, with atypical admiration, that Graceland’s “biculturalism is striking, engaging, unprecedented—sprightly yet funky, fresh yet friendly, so strange, so sweet, so willful, so radically incongruous and plainly beautiful.” Christgau, who graded albums, gave Graceland an A.

Not everyone was happy. In mid-1985, before the world knew about Graceland, Steven Van Zandt, Bruce Springsteen’s longtime guitarist, and the producer Arthur Baker put together the album Sun City, a project publicizing the cultural boycott that gathered literally dozens of stars and superstars, from Bob Dylan to Run-DMC to Bruce Springsteen to Miles Davis, under the rubric “Artists United Against Apartheid.” “I ain’t gonna play Sun City,” went the refrain to the album’s single, also titled “Sun City.” The single came out in October 1985, two months after Graceland’s release, by which time Van Zandt’s, and many others’, anger had jumped notches.4

The UN added Simon’s name to its list of artists who had broken the boycott. Members of the fine L.A. band and critical favorite Los Lobos, one of two non-South African groups to play on Graceland, were bitterly upset at not getting co-writer’s credit, or royalties, for their work on the album’s final song, “All Around the World or the Myth of Fingerprints.” According Los Lobos’s saxophonist, Steve Berlin, Simon’s response was, “Sue me. See what happens.” The band hired a lawyer, and although they eventually dropped the case, remained bitter. “He literally stole the song from us,” said Berlin in 2008, calling Simon “the world’s biggest prick.”

Simon was a predator, his critics said, a musical imperialist. Not only had he, a multimillionaire, profited still further from the music of Black South Africans, but he’d immersed himself in their culture only to emerge with typically insular Paul Simon lyrics, the ruminations of a New York sophisticate. The album’s detractors pointed to its lack of explicitly anti-apartheid songs, “the implication being,” Hillburn writes, “that Simon was just using black South African musicians without having the courage or will to embrace their cause.” Quincy Jones, who had encouraged his friend to go to Johannesburg, reportedly said that if he spent two weeks in South Africa, he would not come back with a song called “You Can Call Me Al.” Simon’s response was apt. Jones was evidently paying more attention to the song’s silly music video, featuring Chevy Chase’s antics, than to the lyrics, in which a self-absorbed, middle-aged New Yorker—someone, that is, just like Simon—upset that his life has no meaning and that he’s starting to get a potbelly (Why am I soft in the middle?/The rest of my life is so hard) finds himself In a strange world/Maybe it’s the Third World/Maybe it’s his first time around. Finding himself surrounded by the sound, the sound, he looks around and sees Angels in the architecture/Spinning in infinity/He says ‘Amen! Hallelujah! In other words, the depressed Westerner (and Simon had indeed been multiply depressed pre-Graceland), finds himself surrounded by the splendid music of “angels in the architecture,” ie., the musicians he had encountered, worked with, learned from, and befriended, and is redeemed, his life changed forever. It’s a well-written, and moving, verse.

Simon’s response to the complaint that he’d written nothing political is more complex. He is correct when he says, in the second interview segment, that politicians, or activists, or anyone, have no right to dictate what an artist creates. On the other hand, we have the famous 1938 poem by Bertolt Brecht, “To Posterity,” written during Brecht’s Danish exile from Hitler’s Germany: “Ah, what an age it is/When to speak of trees is almost a crime/For it is a kind of silence about injustice!” There are times when celebrating the richness of an oppressed people’s culture, their joie de vivre despite their subjection, is not enough; times, that is, that call for strongly expressed political anger, such as Peter Gabriel’s harrowing, and anthemic, 1980 anti-apartheid song “Biko.” Paul Simon made a great album and undertook a vital errand by introducing the world to the riches of South African music. (Graceland was in large part responsible for a late-’80s explosion of Western interest in “world music” in general.) But Simon was wrong, and, I believe, self-serving, when he told me in 1993 (it’s on the third interview segment below), “What I say is this. The politics exists, and the culture exists beneath it like a powerful subterranean river. It’s always there, and the politics comes and goes.” Politics and culture do not run on separate tracks. There are times when it is an artist’s job to make explicitly political statements, ie. times of oppression, autocracy, and brutality.

On February 1, 1987, a troupe of two dozen musicians and singers, including the exiled South Africans Hugh Masakela and Miriam Makeba (neither of whom were on the Graceland sessions), began a six-month world tour. One day earlier, the UN had removed Simon from its list of artists violating the boycott. On February 14 and 15, the ensemble played an outdoor concert in Harare, Zimbabwe, to the immediate north of South Africa. “The crowd was so beautiful,” Makeba said. “I came out onstage and saw the stadium packed with black and white people, and it was a dream that I have carried around with me for years. The first thing I thought was, ‘Why can’t it be like this in South Africa?’ And then I was filled with tears. I’ve got to think it will happen back home someday.’”

It would. Events moved quickly in the next several years. On February 11, 1990, Nelson Mandela, the leader of the anti-apartheid movement and Black South Africans’ larger-than-life hero, was released from prison after 27 years. The ANC, which lifted its cultural boycott in December 1991, invited Simon to perform in South Africa. Already on a world tour, Simon arranged to play two of the tour’s final shows, on January 11 and 12, 1992, in Johannesburg’s 60,000-seat Ellis Park Stadium, for an integrated audience.

The pre-show atmosphere was fraught. A grenade exploded outside the promoter’s office on the day the Graceland troupe arrived. Bomb threats forced the ensemble to switch hotels in the middle of the night. Simon had second thoughts about having brought his son, Harper, on the tour. He wanted Harper to witness history, not stand in harm’s way. It was naive of Simon (and terrible parenting) not to consider that the two often coincide, and to leave Harper back in America.

The ANC may have welcomed Simon, but two militant groups, the Azanian People’s Organization (AZAPO) and the Pan-African Congress of Azania (PAC), bitterly opposed his presence, and warned of violence at the concerts.5 Simon himself may have been in danger. According to Steven Van Zandt, who was in Johannesburg, “the AZAPO showed me that they had an assassination list, and Paul Simon was at the top of it. And in spite of my feelings about Paul Simon”—Van Zandt continued to insist that Simon’s Johannesburg recording sessions had violated the cultural boycott,—and demanded that Simon apologize for holding the sessions—”I said, ‘Listen, I understand your feelings, I might even share them, but it’s not going to help anybody if you knock off Paul Simon.”

In hopes of quelling on-site protests, Simon asked to meet with leaders of the AZAPO and PAC, who agreed to call off their threatened demonstrations. Simon wanted to hold a press conference, so that the groups could announce their withdrawal of protests. Simon’s publicist and advisor, Dan Klores, opposed the idea: “My first reaction,” Klores said, “was that these guys aren’t reliable, they might get to the microphone and turn the whole thing around.”

Which is exactly what happened. At the press affair, which was packed with the world’s media, Simon announced that he had made peace with the militants. He handed the mike over to one of them, who promptly told the press that everything Simon had just said was a lie. Livid, Simon asked the Azanians to meet him in his hotel room, where Simon shoved his accuser against the wall and screamed, “Don’t you ever make me into a fucking liar again!” Klores thought “we might have to fight our way out of that room,” but the protesters simply left. “I had never seen Paul like that,” said Klores. “The next day, he told me he had to do it for Harper. He wanted his son to know that it was important to stand up for yourself.”

The show, and the next night’s, went off without a hitch, with six tanks stationed outside the stadium and a thousand police and security guards patrolling the grounds. “The show,” wrote the New York Times’s Christopher Wren, “broke new ground in exposing the mostly white audience to their country's premier black musicians like the guitarist Ray Phiri and the choral group Ladysmith Black Mambazo.” Simon told Wren that it had been a dream of his to wind up the tour in South Africa. “It’s a rare opportunity, Simon said, “to have a symmetrical ending.” The project had begun in Johannesburg, “and it’s almost poetic,” said Simon, “that it finishes like this. I can feel a sense of completion and move on.”6

Two years out of prison, Nelson Mandela welcomes Paul Simon to Johannesburg for the Graceland concerts. Many members of the troupe, said Simon—Masakela, Makeba, Bakithi Kumalo—had personal memories of Mandela from the years before he was imprisoned. Masakela’s family had been close friends with Mandela’s, and Kumalo recalled standing outside the by-then-imprisoned Mandela’s home, chanting, ‘Madiba [Mandela’s tribal nickname] come home!’”

Below are three audio tracks of Simon and myself discussing Graceland: how it was recorded and written, why he considers it, both song and album, his best work, and his response to the criticism he absorbed on the album’s release and subsequently, and, no doubt, for as long as he lives.

In Track 1, on top, he says that, “Yes, ‘Graceland,’ song and album, are the best work I’ve ever done.” He believes, he tells me, that if he approaches songwriting honestly, his best lyrics come from his unconscious, ie. that “If I feel like, ‘I’m gonna write about about THIS,” ie., picks out a subject prior to composing and forces himself to stick to it, rather than going with the flow—the song will be, as he puts it, “contrived, and I don’t want to hear it.” For the mature Simon, a song takes shape during, not prior to, its composition;

In Track Two, in the middle, he talks about the experience of working with Graceland’s musicians. Somewhat naively, as Simon points out, I had the notion that working with tremendously gifted musicians, from completely different backgrounds from his, and with completely different daily lives—that this must have been a life-changing experience. Of course it was, he says, but in some important ways it wasn’t. He mentions three musician in particular: Ray Phiri, who played on the Graceland album and tour; Hugh Masakela, who played on the tour, and the Cameroonian guitarist Vincent Nguini, who first played with Simon on the subsequent album, Rhythm of the Saints, and was a member of Simon’s band for decades. Simon makes several points:

These are musicians and he’s a musician, and they’ve spent their lives working on the same few problems. Though they live thousands of miles apart and were raised, and lead their lives today, completely differently from one another, they confront the same problem daily: how to work with others to make a really good piece of pop music. “My father was a musician,” says Simon, “and brought me up to love musicians, and I love musicians.” He and they are members of the same tribe, not mutual aliens.

Simon wanted to be just as clear that the Graceland musicians are not merely symbols, heroic representatives of an oppressed people, but multifaceted, three-dimensional guys with real-life, down-to-earth concerns who enjoy some of the same things Simon does (he and Nguini like to watch boxing; Masakela and Simon are partial to smoking weed) and couldn’t care less about others. “If you relate to Ray Phiri as a Black South Africian musician, period,” Simon said, “you’re relating to a very small part of who Ray Phiri is: as Simon said, “a moody guitar wizard who’s shy, quiet, can’t hold onto money, and makes bad investments. That’s my point: the variety that I found was the variety of people in life.” In some ways, making Graceland was a profound, life-changing experience; in some ways it didn’t change Simon at all, but was just another gig.

In Track Three, Simon responds, heatedly, to criticism of Graceland: the way he went about making it, and the product that emerged. The triple issue of "Graceland”/apartheid/art is a complex one, and Simon addresses it passionately. He particularly takes issue with Quincy Jones’s remarks, mentioned above, about the song ‘You Can Call Me Al,’ and with similiar complaints that Graceland’s content was not political. Do you agree with Simon counterargument ? Disagree? As you’ll realize on giving the matter some thought, it ain’t that simple.7

“Graceland, man, that record changed my life,” said Kumalo, who went on to play in Simon’s various bands for 30 years. “It was my passport to the world.” That’s Kumalo playing the jaw-dropping, four-second bass lick that stops traffic at 3:43 of “You Can Call Me Al.” (In a 2013 New York Times essay, Simon referred to Kumalo’s “magical and impossible-to-play” bass run. It is, in fact, literally impossible to play. Roy Halee made it so. Back in New York after the sessions, Halee re-recorded Kumalo’s lick in reverse, making a virtuoso piece of playing sound even more astonishing. The only problem is that it can’t be duplicated live.

Graceland’s musicians were collaborators from the start. A part improvised at Ovation Studios by the accordionist Forere Motloheloa turned into the volcanic opening of Graceland’s first song, “The Boy in the Bubble,” and Ray Phiri came up with a guitar lick that became the opening, and defining, riff of “You Can Call Me Al.” Phiri received royalties for the latter song and one other, “Under African Skies.” Royalties for arranging, not composing—Phiri was credited as a co-arranger, not co-composer—are rare. Motloheloa received co-writer credit, and royalties, for his contribution to “The Boy in the Bubble,” as did Shabalala on “Homeless” and “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes.” Three other South African musicians received co-writer credit. South African musicians were paid $15 an hour at the time; Simon paid his Graceland players $196.41, triple scale, or the highest pay rate, in the U.S.A.

Since Simon’s imagination had originally been kindled by a record of South African accordion music, he was interested in including other genres that featured accordions, such as the Black and Creole genre of zydeco. This led him to zydeco country, or south-central and -western Louisiana, and to the zydeco accordionist and bandleader Alton Jay Rubin, who called his band Good Rockin’ Dopsie and the Twisters and played accordion on the Graceland track “That Was Your Mother.” The accordion is also what attracted Simon to Los Lobos (see above), whose David Hidalgo was a master accordionist (although Hilburn is incorrect in calling Los Lobos’s sound “accordion-driven”; Hidalgo was primarily a guitarist, and a fine one, as were two other Los Lobo members. If anything, Los Lobos was, and is, guitar-driven).

When Graceland came out, Rubin claimed that Simon had plagiarized Rubin’s song “My Baby, She’s Gone,” but decided not to sue. Los Lobos’s claims to have co-written Graceland’s “All Around the World or The Myth of Fingerprints” were, as we’ve seen, far more strenuous, and although they finally decided against taking legal action, remained bitter for decades—see Los Lobos’s saxophonist Steve Berlin’s 2008 remark about Simon.

In this writer’s opinion, including Los Lobos and Good Rockin’ Dopsie on Graceland was, regardless of legal issues, questionable aesthetically. Featuring the accordion, which figured in some, but not a significant amount of, South African pop music on an album inspired by, drawn from, and essentially about that music, was not one of Simon’s more astute musical decisions.

A little-known fact about Graceland is that when Simon began preparing lyrics, he took the unusual step of asking a close friend at the time, the New York Times book critic Michiko Kakutani, to be his editor. “She was my editor on Graceland. That’s the first time I’d ever had an editor, whom I could ask, ‘Does this make sense?’ ‘I was thinking of using this line here—what do you think?’ I found it very valuable.”

Sun City was a resort, casino and concert venue in Bophuthatswana, one of 10 “bantustans,” or “homelands,” as they were called, established by the South African government, whose rigidly apartheid regime dated back to the late 1940s. Millions of black South Africans were forcibly relocated to the bantustans, which were, essentially, large-scale versions of townships, the all-black slums erected, largely during the 1940s, on the periphery of South Africa’s major cities. The bantustans were declared independent states—Bophuthatswana in 1977—but were recognized as such neither by the United Nations nor any government in the world. The bantustans remained in every major respect under white South African rule. Their administrations were, at their core, puppet regimes.

Developed by the South African entrepreneur and hotel magnate Sol Kerzner, Sun City opened in 1979, Blacks were allowed to attend concerts (though few could afford the price of admission), making Sun City a showpiece of integration. Sun City was immediately placed under cultural boycott by anti-apartheid groups; nonetheless, many of the world’s most famous entertainers were offered, and accepted, vast sums of money to perform: Frank Sinatra in 1981 (who was reportedly paid $2 million for nine shows); Dolly Parton and Olivia Newton-John in 1982; Elton John, Rod Stewart, and Paul Anka in 1983, and Queen in 1984. Others who accepted invitations were the Beach Boys, Cher, Liza Minnelli, and many others. Whites, and presumably very flew Blacks, flocked to the Sinatra shows especially, shuttled daily from Johannesburg to Sun City on five planes and 30 luxury buses. The cheap seats went for $17, or four weeks’ average wages for Blacks; The pricier seats, which cost between $55 and $85, were snapped up quickly. It’s doubtful that any Blacks besides Bophuthatswanan dignitaries attended; seventeen dollars, the price of the cheapest Sinatra seats, were the equivalent of four weeks’ wages routinely paid blacks.

Paul Simon’s friend and a lifelong liberal, Linda Ronstadt, who became entangled in the issues surrounding Sun City, was a strange case. In 1983, Ronstadt accepted a reported $500,000 to play Sun City, claiming, when her decision was denounced arose, that she was unaware of the cultural boycott. Simon defended her, saying, “She made a mistake. She’s extremely liberal in her political thinking and unquestionably anti-apartheid.” One of the reasons that Simon, who had twice turned down $500,000 offers to play the venue, refused to sing on the album Sun City was that the single denounced a laundry list of performers, including Ronstadt, who’d played there. Simon had been sent an early take, said van Zandt; when the song came out, the names were removed. Simon nonetheless refused to join Artists United Against Apartheid; he and van Zandt, who roundly condemned Simon for recording in Johannesburg, were hardly friends. Their enmity has stood the test of time; in 2016, Van Zandt, while calling Simon “one of the greatest songwriters of all time,” found it “extremely arrogant of him to think he’s smarter than the UN [which, as we’ve seen, had withdrawn Simon from its non-boycotters list before he played Johannesburg].” An ornery Simon said to me, “Why should I tell the world I ain’t gonna play Sun City? I’d already turned them down, twice!” Feisty to the core, Simon included Ronstadt on Graceland, which, the American music journalist Nelson George wrote, “was like using gasoline to put out birthday candles.”

Azania, a millenia-old term for Southern Africa, was revived in the 20th century by militant groups such as AZAPO and PAC.

Graceland, as I mentioned in my introduction to the series, was a spectacular sales success, selling 16 million copies, second only to Bridge Over Troubled Water. It won the 1987 Album of the Year Grammy, Simon’s third, along with Bridge and Still Crazy After All These Years. Two other artists, Stevie Wonder and Frank Sinatra, have won three Album of the Year Grammys. Taylor Swift, whose music is not on Simon’s (or Sinatra’s, or Wonder’s), artistic level, has won four, so far. In 1988, “Graceland,” the single, won that year’s Grammy for Record of the Year (these awards categories have a terminology and logic all their own). Graceland, the album, wound up spending 97 weeks on Billboard’s Top 200 albums chart.

At 6:43 of audio segment #3, I refer to a friend of Simon’s who had recently been killed. This was Headman Shabalala, Joseph Shabalala’s brother and a member of Ladysmith Black Mambazo, who was shot and killed in December 1991 by an off-duty white security guard in an apparently racially motivated crime.

Whatever happened to Heidi Berg? You know why we don’t know? Paul Simon.

Great album but I like Rhythm of the Saints even more.

More subtle and sublime.