Merle Haggard Headed South on the I-5, Bakersfield-bound

"What did you learn from listening to Crosby?" "Ha! Haha! I learned that he was probably the greatest singer of the goddamn century! Ain't nobody around that's ever come close to that cat."

In mid-1996, I profiled one of my half-dozen, or fewer, greatest musical heroes, Merle Haggard. I wrote the piece, which combined a critical assessment of Haggard’s magnificent oeuvre with an interview, for the August, 1996 issue of The Atlantic, which mistitled it “The Last Roundup” —Merle, like most country singers, had never had any truck with cattle, ropes, or saddles. The interview, which packed a whole lot into 36-plus minutes, is below, unedited and in its entirety.

For those of you unfamiliar with the man and his work, here’s how the Atlantic piece began:

“MERLE Haggard is a commanding figure in late-twentieth-century American popular music, a country-music superstar whose career, documented in the new collection Down Every Road [a four-CD, 100-song overview] has spanned more than one seismic shift in our recent cultural history.

“Before he stiff-armed the counterculture in 1969,” I wrote, “with his hippie-baiting anthem ‘Okie From Muskogee,’ Merle Haggard was on his way to an unlikely apotheosis. Rolling Stone lionized him as an auteur and an unlettered poet who transcended the limits of a trashy genre. The genre itself fascinated hippies. The Grand Ole Opry, Goo-Goo Clusters, Tammy Wynette--wow! To the children of affluence, this was surreal kitsch, exotic yet on native ground. Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda rode out to discover America in Easy Rider. Merle Haggard was the son of Dust Bowl refugees and sang about it; he was an ex-con and sang about that, too. "I turned twenty-one in prison / Doin' life without parole." So what if the fellow wasn't a murderer? He was the real thing-- ten times as real as Bob Dylan, that middle-class renegade.

“But the real thing got nasty and bit the counterculture's hand. "Okie" showed the hippies where Merle's heart lay: with the crackers who blew Hopper and Fonda away. With white working-class America, not romanticized à la Marcuse but in its red, white, and hippie-stomping blue; with the crowds of crew-cut flag-wavers who cheered Merle on all across America in the autumn of '69: "We don't smoke marijuana in Muskogeeee . . . "

“Recoiling, the longhairs vilified Haggard ("the Spiro Agnew of music," one critic called him) and then forgot about him. Haggard shrugged and went his way, singing for his faithful fans and slowly building country music's greatest body of work since that of Hank Williams.”

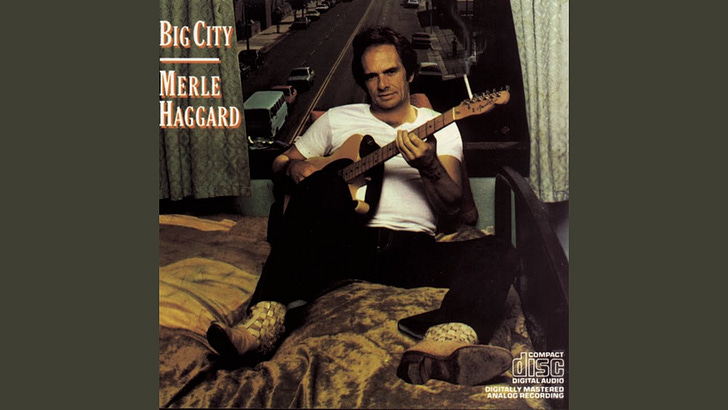

Quintessential Haggard: the workingman’s complaint “Big City.” “I’m tired of these dirty old sidewalks/Think I’ll walk off my steady job today….” You’ll notice that the piano player, Mark Yeary, is playing James P. Johnson-style stride piano. The only country artist ever featured on the cover of the jazz bible Down Beat, Merle proudly called his music “country jazz.”

Fast-forward to 1996. By the time I connected with Merle,1 country music’s popularity had mushroomed, and his had waned. As great an artist as he remained—I saw him several times in the ‘90s and was blown away each time—it had been nine years since his last #1 hit, “Twinkle Twinkle Lucky Star.” (He scored a total of 38 country #1’s, starting with 1966’s “I’m a Lonesome Fugitive.”2) Merle’s disdain for the sounds coming out of mid-’90s Nashville cannot be fobbed off as a crabby old-timer’s sour grapes. Aesthetically, his remarks were spot-on:

“‘These songs they got on the radio now, my wife says it sounds like they're singin' about air. What more can they do to the sonofabitch? They've got it down to a science. They've got grooming classes where they can turn out Elvis Presleys -- one a day, I think. They gather up at nine-thirty in the morning, they go off in little groups and come back with these prefabricated songs about things that never happened, and it sounds that way. [Merle was an autobiographical writer at heart, his songs drawing on the facts of his life.] It's so refined, it's so perfect, it's so in tune, and there's no feel, no God-dang soul to it, there's no story, there's no melody, and I just wish I could say somethin' else, but that's my opinion.’”3

Thus Merle’s feelings about the Garth Brooks era; one shudders to think what he’d have to say about Morgan Wallen or Luke Combs.

Undated concert video. From the Atlantic article: “The bedrock emotion in his songs is probably a deep, stoic sadness—”I grew up in an oil town but my gusher never came in,” he sings in the beautiful 1985 elegy "Kern River,” about how the swift-running river, which Merle fished as a boy, claims the life of the narrator’s girlfriend. “It’s not deep nor wide but it’s a mean piece of water, my friend.”

But I haven’t posted this interview, nor these paragraphs, in order to provide a portrait of the artist as an old grouch (Merle was, in fact, only 59 in 1996; the year before, he’d played more than 100 dates). I’m here to give you access to a complex, keenly intelligent individual, many of whose traits came as surprises to me, including a palpable warmth, a generosity of spirit—his is so often portrayed as a pinched, bitter personality.

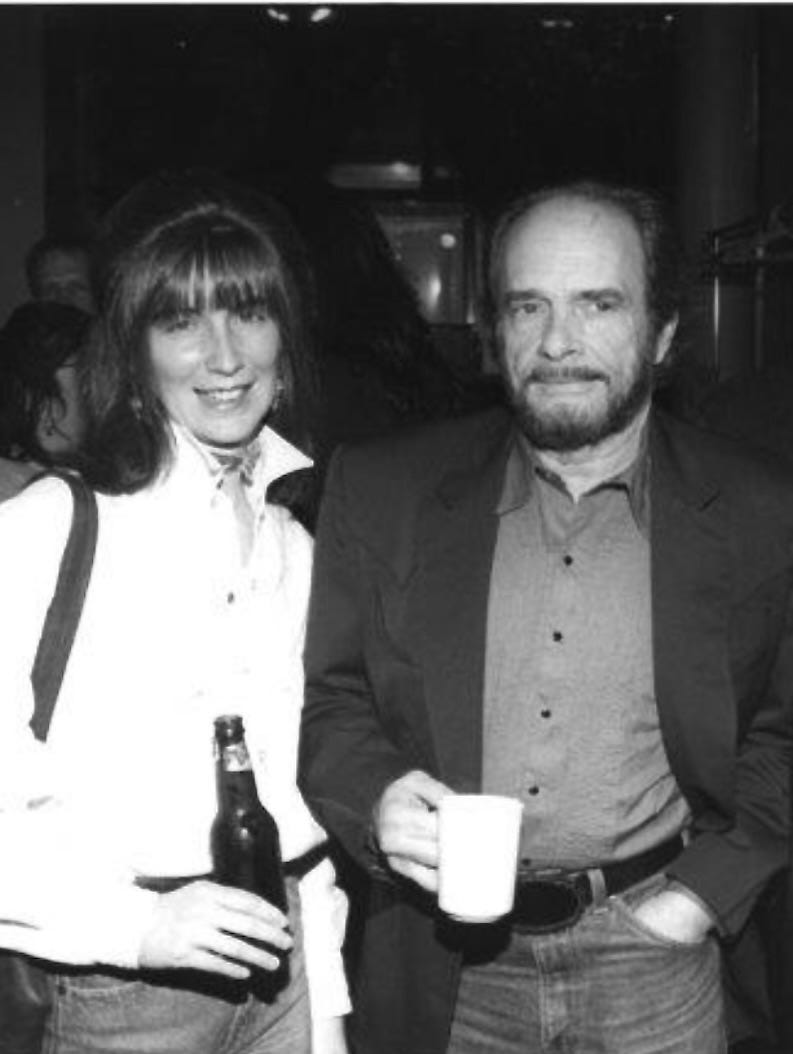

FISH OUT OF WATER: Merle, at a 1996 record-release party in Manhattan, exquisitely uncomfortable despite the reassuring presence of the author’s then-wife, Colleen Hughes.

So here are a master’s thoughts on the crafts of singing and songwriting (a special treat: the story of how he came to write one of his loveliest songs, “Kern River”).4 You’ll hear a ready, dry sense of humor, including a laugh that was all Merle’s own, described by the writer Bryan di Salvatore as “a series of gravelly barks—ha ha ha haaaa ha ha… exaggerated and oddly phonetic, as if issuing from an extraterrestrial who had learned to laugh by reading a book about earthlings.” You’ll learn the breadth of Haggard’s musical tastes and knowledge—this was a sophisticated, highly trained, if largely self-taught, musician (he did seek out guitar teachers at various times), with a boundless curiosity. Merle will refer here and there to people you probably won’t have heard of: the mysterious minstrel-show singer Emmett Miller, for instance, whose life Haggard had taken it upon himself to investigate. But I’m going to resist the urge to smother you with yet more edifying footnotes. It’s time to give Merle his say.

Merle and I spoke in April, 1966. He had a ‘90s-style car phone, and, with his wife, Theresa, was driving from his northern-California home, near Redding, to his native Bakersfield area. Haggard had organized a benefit concert for his lead guitarist of 21 years, Roy Nichols—"an icon, as you know,” said Haggard. Nichols had recently suffered a stroke, was no longer able to play, and was accruing big medical bills. Roy Nichols was the first sideman Haggard hired, in 1965, for Merle’s unknown band, the Strangers. “Because of Roy, my career commenced,” Haggard once said. Nichols died in 2001. Merle Haggard, who’d fought off multiple illnesses, including cancer and pneumonia, for decades, finally died in 2016, on his 79th birthday. Country to the end, a fading Merle asked to be carried onto his tour bus, which is where he passed away.

Interestingly, “Fugitive,” an ex-con’s lament, was written not by the ex-con himself but by the husband and wife team of Liz and Casey Anderson.

The Washington Post’s book critic and columnist, Jonathan Yardley, a big country-music, and Haggard, fan, happened across my article and was beside himself with admiration for Merle’s remarks. In his August 26, 1996 Post column, which he titled “Take It Away, Merle,” Yardley wrote, “The first time I read those words, I was knocked right out of my socks. There, in one paragraph, was everything I'd been trying to say about contemporary American fiction for a decade and a half, but said with a voice of experience I cannot hope to possess. Any time Haggard wants work as a literary critic -- God knows why he would -- this space is his for the asking.”

Haggard was astounded to hear that I’d checked in with BMI to learn that he had written and registered 346 songs to his songwriting hero, Willie Nelson’s, 292. “Well, kiss my ass!” said Merle. “I didn’t know that!”