Great Guitar Solo #2: E.C. Was Here

On "Crossroads," Cream's 1968 live cover of Robert Johnson's "Cross Road Blues," Eric Clapton plays two solos. The first is unexceptional, the second is for the ages.

Although it’s impossible to disregard Eric Clapton’s misbegotten anti-vaccination stance during the COVID pandemic, as well as the long trail of racist remarks that the press has rediscovered in recent years, it’s just as impossible to deny his greatness as a guitarist. It is Clapton who plays the second of what I called in my Substack of February 3rd “the three rock guitar solos that never fail to push my button more emphatically than any others, of any genre.” The first, which I wrote about in that February 3rd piece, are the 37 seconds of mastery with which The Band’s Robbie Robertson closes the group’s 1969 song “King Harvest (Has Surely Come)”.1

The British band Cream (Ginger Baker, drums; Jack Bruce, bass, harmonica, and most vocals, and Clapton on guitar) lasted for barely two years, from July 1966 to November 1968, and released just four albums while they were together.2 They were among rock’s first power trios, and are probably the greatest. (The Hendrix Experience was essentially Jimi and two sidemen; Cream’s three members contributed equally).

On March 10, 1968, Cream played San Francisco’s Fillmore Auditorium, where they recorded a song that had been in their repertoire since the group’s founding: the 1930s Mississippi Delta bluesman Robert Johnson’s “Cross Roads Blues,” which Clapton, an ardent Johnson admirer, brought into the band. Cream shortened the title to “Crossroads.”

On the March 10th “Crossroads,” which is on the band’s double album Wheels of Fire,3 Clapton sings one of his then-infrequent vocals and plays two guitar solos. The first (1:26 to 2:11) lasts for two choruses, the second (2:31 to 3:34) for three. Clapton’s second “Crossroads” solo is the second of the three solos that are at the top of my personal pantheon. As I indicated in my piece on Robertson’s “King Harvest” solo, I’m not quite arrogant enough to call my three favorites the “three greatest.” There are no three greatest.

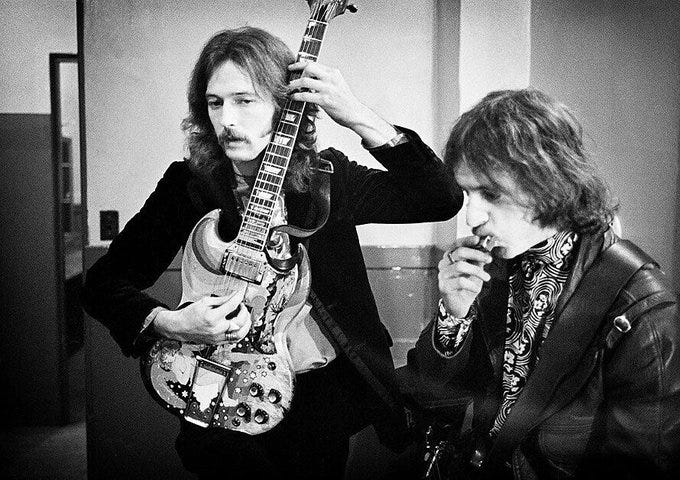

San Francisco, March 1968: Jack Bruce (r.), blowing his harmonica. On the left is Eric Clapton with his beloved 1964 “Fool” Gibson SG. The origin of the guitar’s nickname? Its body was given its psychedelic paint job by the Dutch design collective The Fool.

“Crossroads” is, lest we forget, a blues. It has only three chords: in this case A, D and E7th.4 The blues’s minimal harmonic structure is a boon to the creative improviser. There aren’t a lot of chords to fence you in, and if you can avoid the lazy player’s way out—the grab-bag of rote blues licks—the sky’s the limit. A chorus of the blues has 12 bars, as opposed to the pop chestnut’s 32, and no bridge; in pop standards, the bridge consists of bars 16 through 24.

Johnson’s original and Cream’s cover, recorded more than 30 years apart, are virtually two different songs. For one thing, Clapton lifts a verse from an entirely different Johnson song, “Traveling Riverside Blues,” and sings it in “Crossroads,” twice.5 He also omits two of Johnson’s verses. But these are relatively superficial alterations.

Like many blues, especially rural blues of his day, Johnson’s “Cross Road Blues” alternates between a shuffle rhythm and conventional 4/4 time. Lurking within Johnson’s wavering rhythmic pattern, Clapton heard another: the classic rock & roll beat, a propulsive forward thrust known as the straight-eight, or eight eighth-notes per measure, of equal dynamics, a machine-gun-like bop-bop-bop-bop-bop-bop-bop-bop. “Out of all the [Johnson] songs,” Clapton told a writer in 1997, “Cross Road Blues” was the easiest for me to see as a rock and roll vehicle.”

Robert Johnson’s King of the Delta Blues Singers, compiled in 1961 under the direction of the great producer and talent scout John Hammond, was sacred to Sixties blues aficionados on both sides of the Atlantic. This is the version of “Cross Road Blues” (Johnson recorded two; the other was not released until years later) that spellbound a young Eric Clapton. Johnson recorded it in November, 1936, aged 25. He died less than two years later.

Apart from switching between the shuffle and straight 4/4, Robert Johnson gives himself lots of leeway in “Cross Road Blues.” Sometimes he’ll sing a line with no guitar accompaniment. He also, typically of bluesmen, felt free to add a bar or two to the standard 12, which gives many of his blues a staggered gait. Johnson played for frolics, or dances, whose attendees had to be on their toes. If a chorus was 13 bars instead of the standard 12, it was easy to trip over your feet, and pull your partner off-balance, too. Modernization means standardization, and in “Crossroads,” Cream stuck to an invariant 12-bar blues chorus. No more 13-bar choruses, thank you. This is a rock concert, not an old-time rural frolic.

In Ginger Baker’s hands—in his feet, rather—the straight-eight can become unattractively relentless. Baker used two bass drums, to my mind, unnecessarily, unless it was purely for power. For long stretches (2:53 to 3:13, for instance), he doesn’t take advantage of the rhythmic possibilities offered by two bass drums (as The Who’s Keith Moon did), but lays down an unvarying, unsyncopated, in other words, boring, beat.6 Baker’s hands (and sometimes his feet) are a different matter, goosing a listener with unexpected snare drum and tom-tom offbeats that make things interesting.

Except for during Clapton’s two solos, Clapton and Jack Bruce play the same riff over Baker’s essentially unvarying beat. Clapton’s first solo is the signal for the other two to start improvising as well. In the solo’s second chorus, Bruce is especially imaginative, abandoning his straight eighth-notes of the first chorus to play a creatively syncopated line. Baker goes back and forth between his boring bass-drum routine and more inspired passages, when his snare, tom-toms and bass drums interlock in complex, complementary licks. Baker didn’t challenge himself often enough; when he did, the results could be splendid. As for Clapton, who set a high bar for himself, the two choruses that constitute his first “Crossroads” solo would have been triumphs for most guitarists; for this one, it was OK but nothing to write home about.

Wheels of Fire’s March 10th “Crossroads” was recorded not at Winterland Ballroom, as has often been written, but, as the above YouTube correctly has it, at the Fillmore Auditorium. There is no video of the Fillmore performance. The YouTube of Cream playing the March 10th “Crossroads” is, in fact, a fake. The video is from Cream’s November 1968 Royal Albert Hall performance (Clapton having gotten rid of his moustache and switched guitars; see Note 7 just below), cleverly edited to fit the “Wheels of Fire” audio. The actual Albert Hall performance, with the same video, is on YouTube, too, with an obviously different, inferior version of “Crossroads.” 7

Both of Clapton’s “Crossroads” solos, but especially the second, are not just successions of standard blues licks, as too many blues solos are, but of self-contained yet connected phrases, “lines that build and develop into statements,” as one writer puts it (my emphasis), whose inner logic carries them from one to the next, yielding a single, unified statement: a successful solo.

For all its cohesiveness, Clapton’s second “Crossroads” solo (2:31 to 3:34) is a high-wire act, the soloist barely averting train wrecks at the last millisecond. I’ll say it here: Clapton may never have equaled this solo. While the first solo never rises above a moderate emotional pitch, in the second, Clapton means business from the first bar-and-a-half: a stampede of blindingly fast notes (2:31-2:34) that turns into a lengthy but entirely lucid narrative, propelling Clapton all the way to the end of the first chorus (2:52.) I’ll note that during Clapton’s blitzkrieg at the start of Chorus #1, Bruce becomes, essentially, a second soloist, abandoning the accompanist’s straight-eight beat for improvised figures high up on the neck of his bass, carrying on a sophisticated conversation, as it were, with Clapton. Speaking of barely averted train wrecks, there’s one that starts at 2:44, towards the end of that first chorus, where Clapton seems to lose the beat, and his two bandmates, but rescues himself at 2:50, hitting a piercing high-A (the tonic, or home base) to rejoin the others.

Clapton may have had this moment in mind when he told the writer Dan Forte, in 1985, "I wouldn't be at all surprised if we weren't lost at that point in the song, because that used to happen a lot. I'd forget where the 1 was, and I'd be playing the 1 on the 4, or the 1 on the 2…. [E]veryone can pat themselves on the back that we all got out of it at the same time." Still, the endlessly self-critical perfectionist couldn’t help but add that such bare escapes “rankle me a little bit," as he told Forte.

The notes in Chorus #2 fly at a less speedy pace, featuring one of Clapton’s trademarks, even in his early days: string-bending. He ends the chorus with his own variation on the classic blues turnaround (3:07 to 3:14).8 The third chorus (3:15 to 3:34) starts with Clapton in a convincing impersonation of a bulldozer driver, playing brutally powerful double stops: bent thirds, in this case.9 This final chorus, which I will simply let speak for itself, is one of the most exciting moments of Clapton’s entire career. He was not yet 23 years old.

A controversy has followed Wheels of Fire’s “Crossroads” down through the years, like a tin can tied to a dog’s tail. The renowned engineer/producer Tom Dowd, who recorded and/or produced Clapton in Cream, Derek and the Dominos and solo, always maintained that the album’s version of “Crossroads” (and Cream’s many other recordings of the song), was edited down to its 4:18 length from a much longer rendition. In the live portion of Wheels of Fire, “a lot of things were ultimately brought down to shorter versions than were played onstage,” Dowd told Guitar Player magazine in 1985. “'Crossroads' onstage, for instance, was never under seven to 10 minutes long. So the solos between the vocals were edited.”

I believe that Dowd is wrong about Wheels of Fire’s “Crossroads,” and other versions as well. He is definitely wrong about what is probably Cream’s earliest recorded version of “Crossroads.” It’s on a bootleg album, available on YouTube, that Cream cut at the popular London club Klook’s Kleek on November 15, 1966, shortly after recording their first album, Fresh Cream. The Klook’s Kleek “Crossroads” comes in at 3:10 seconds, hardly Dowd’s “seven to 10 minutes.” (Granted, this was an early performance of the song; it’s possible that as Cream’s members got more comfortable with each other, significantly longer live versions of “Crossroads” resulted.)

But not the four versions of the song that appear on the expanded, four-CD version of Goodbye, recorded during Cream’s swan-song tour of autumn 1968.10 We’ve got versions recorded on October 4 at the Oakland Coliseum (length: 4:07), October 19th at the Los Angeles Forum (4:07), October 20th at the San Diego Sports Arena (4:02), and November 26th at London’s Royal Albert Hall (4:02). Would Tom Dowd have put in the time and energy required to edit four “seven-to-ten-minute” recordings of “Crossroads” down to four minutes? Not bloody likely. Especially since since all four versions of the Clapton guitar feature “Spoonful” were left at what had to have been their original lengths, which range from 12:54 to 17:26. None of the tour’s three versions of Baker’s drum extravaganza, “Toad,” are less than 10:42. It’s almost impossible not to conclude that four minutes and change was the length that the band customarily played “Crossroads.”

Further, Tom Dowd wasn’t at the concert where Wheels of Fire’s “Crossroads” was recorded. He co-engineered the album’s first volume, which was cut in the studio. The second, live volume, was engineered by Bill Halverson, a staff engineer at San Francisco’s Wally Heider Studios. Who was Dowd to say how long March 10th’s onstage “Crossroads” was? He was elsewhere.

There are a number of other counter-Dowd arguments, but I’ll end with this next. As its title indicates, the music writer Edoardo Genzolini’s deeply researched 2023 book Cream: Clapton, Bruce & Baker Sitting on Top of the World: February-March 1968, Genzolini’s book narrows its focuses to the period just before, and during, the making of the live portion of Wheels of Fire. Genzolini recently spoke to Neville Marten, a writer for the musicians’ website MusicRadar, about the March 10th concert. Referring to the powerful music promoter Bill Graham, who owned the Fillmore and Winterland, Genzolini said, “Bill Graham’s recording on reel-to-reel from the first set of March 10th, preserved at Wolfgang’s Vault [a San Francisco archive that contains Graham’s vast collection of concerts recorded at his venues], as well as an audience recording of the complete March 10th sets, proves it to be unedited.” [“Wolfgang” was Graham’s family nickname.]

“Wolfgang’s Vault itself,” continues Marten, citing an unnamed source—probably the archive’s founder/owner, Bill Sagan—underscores this view, saying, “Many have claimed Clapton’s blistering solo is a result of studio overdubbing, but here it is on this raw two-track recording, proving that one of the most blazing guitar solos of all time was indeed done spontaneously, live onstage.”

Eric Clapton, as has many a great artist, peaked early. The concensus that I’ve encountered, with which some will undoubtedly disagree, is that Clapton’s genius carried him through Layla, recorded and released in 1970, and then vanished, rarely if ever to return. Name a post-Layla song that rises to the level of his work on Fresh Cream, (parts of) Disraeli Gears, the fury of Wheels of Fire’s “Crossroads,” and (parts of) Layla. “Lay Down Sally”? “I Shot the Sheriff”? “Wonderful Tonight?”

I have often pondered something that Ivan Karp, the art-gallery director who discovered Andy Warhol, told me years ago, when I was writing a Warhol biography. “Andy was at the peak of his obsession from 1962 to maybe 1966,” said Karp. “When he got to 1967, 1968, he had exhausted his fund of fantasy. You see it again and again."

Warhol, Pollock, Fitzgerald, Ellison, Wordsworth, Rimbaud, Nijinsky, the Beatles, Aretha Franklin post-Amazing Grace. There are two kinds of genius. All of the preceding artists' creative explosions were just that, as short-lived as they were spectacular. Then there are Michelangelo, Titian, Mann, and O'Keeffe, who produced great work in old age. Why do some artists flame out after a few miraculously productive years: a short time here and a long time gone?

In the small world of rock stars, paths often converge. Not long after The Band released their first album, Music from Big Pink (1968), Eric Clapton visited Robbie Robertson at the latter’s Woodstock, NY home. “Many years later,” Robertson writes in his memoir, Testimony, “when Eric inducted The Band into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, he admitted that when he came to visit us in Woodstock, he was really coming to ask if he could become a member of The Band but never worked up the nerve to ask. I jokingly asked if he was suggesting that we have two guitar players, or did he want to take my job?”

Cream’s fourth album, Goodbye, was recorded in October and November 1968. By the time it was released, February 1969, Baker, Bruce and Clapton had gone their separate ways.

Wheels of Fire was the first double album to hit #1 on Billboard’s Top 200 and the first to go platinum, selling a million-plus copies.

Some blues have fewer than three chords. John Lee Hooker was famous for his one-chord blues.

The smuggled, repeated verse is: “Going down to Rosedale/Take my rider by my side/We can still barrelhouse, baby/On the riverside.”

A music writer once played Baker’s numbingly long, repetitive solo feature, “Toad” (it clocks in at 16:16 on Wheels of Fire) for the great jazz drummer Elvin Jones, who was bored to tears. “They oughta take his ass and fly it to the moon,” Jones said.

Re the Fillmore/Winterland confusion: As Bill Halverson, who engineered the March 10th concert, explains in Genzolini’s Cream book, “That string of shows [March 7th to March 10th] had been booked for four nights at Fillmore. Bill Graham overbooked it, but Winterland [a much larger venue] was available. So we had to do March 7th at Fillmore, tear everything down, go Friday and Saturday at Winterland, and go back to Fillmore for Sunday, March 10th.”

The Royal Albert Hall video I refer to above, incidentally, shows Clapton playing a Gibson ES-335 (B.B. King’s and Chuck Berry’s guitar of choice). He may have been playing it at Albert Hall in November, but in March he was playing the Gibson “Fool” SG that he’s holding in the photograph near the top of this piece. That makes sense; the photograph was taken in March. Clapton, who for years has been closely associated with the Fender Stratocaster, didn’t start playing it until 1970, probably under the influence of Jimi Hendrix.

A turnaround is the short passage in a song that ends one chorus and sets the stage for the next. In blues, there are a handful of standard turnarounds; depending on his creativity, a player can ring his own changes on the old standbys.

A double stop on guitar is two different notes played simultaneously.

Goodbye was originally released (see footnote #2) as a six-song, 30-plus minute album. An expanded, 4-CD box set was released in 2020.

Wow. Thanks for this Cream was one of my fave bands. Though I was never that big a fan of Eric Clapton, I do appreciate a lot of his music besides with Cream. We have to detach who they are personally sometimes when it's abhorrent so we can still be fans of their music. I do this with Roger Waters.