Dylan, Warhol & Edie Sedgwick: Three on a Tinderbox

Shortly before Andy Warhol and Bob Dylan’s brief, tense encounter at Warhol’s Factory (see previous post), they had a briefer, tenser encounter at Dylan's favorite watering hole

Early in 1965, the year that Andy Warhol’s art studio “turned into the exploding Factory,” as Warhol’s chief factotum, Billy Linich, put it, Edie Sedgwick, 22, entered Andy Warhol’s life. “Beautiful, pixieish, and aristocratic, Edie gave off an indefinable glow,” I wrote in POP, my 2009 Warhol biography.1 Another Factory habitué, the playwright and scenarist Robert Heide, described Edie similarly: “She gave off this eerie light and energy. It’s as if Edie was illuminated from within.”2

Warhol, the immigrants’ son raised in near-poverty, was as enchanted by Edith Minturn Sedgwick’s lineage as he was by her mercurial charm. Edie’s great-great-great-grandfather Theodore represented Massachusetts in the U.S. Senate from 1796 to 1799; her great-great-uncle Robert Shaw commanded the all-Black Civil War regiment memorialized in the movie Glory, and another great-great-uncle, Endicott, founded the exclusive prep school Groton.

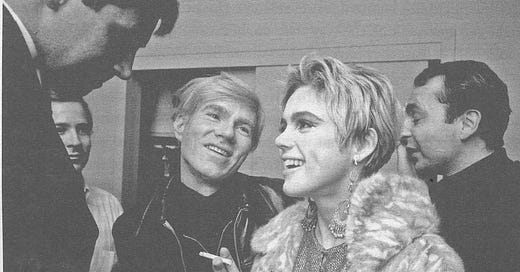

Andy Warhol, besotted with the 22-year-old Edie Sedgwick. His infatuation didn’t last.

Raised on a three-thousand-acre ranch near Santa Barbara, California, Edie was intimate with high society on both coasts. Less alluringly, she had been committed, twice, to mental hospitals. Edie alternately worhsipped and loathed her preening, domineering father. Francis Sedgwick, “Duke” to some; to others, “Fuzzy,” terrorized his children emotionally. Edie’s older brother Minty, whom she adored, was in his third mental hospital when he acknowledged his homosexuality to his father, whose response was, “I’ll never speak to you again; you’re no son of mine!” Minty hanged himself. “The whole family story is not to be believed,” Edie told Nora Ephron in “Edie Sedgwick, Superstar,” a New York Post Sunday Magazine feature. “Very grim. It teaches you a great deal, really tremendous amounts of things about human nature and all the terrible things that people do to each other. I’m going to find my own way, free of my parents.”3 Not likely: shortly before her arrival in New York, she inherited $80,000 from her grandmother ($800,000 in today’s dollars). She spent it in six months,4 according to her friend Tommy Goodwin, whom she hired as her chauffeur. “It was the gravy train,” said another friend, the future rock impresario Danny Fields. “She didn’t know half the people she took to those dinners of hers.”

Edie attracted the press like flies. Apart from Ephron’s piece, there was a New York Times profile; a Life magazine photo spread (“The Girl With the Black Tights”—Edie evidently pioneered the so-called “no-pants” look, which, given the ubiquity of leggings, makes her a cultural, or at least sartorial, trailblazer); a famous full-page Vogue snap of Edie performing an arabesque on a leather rhinoceros in her apartment, a guest spot (with Warhol) on The Merv Griffin Show, and countless other appearances in the public eye. She made a good beard for Andy. “His constant companion,” as Time reported, she helped neutralize the homophobia that hounded him. “It was a whole new paparazzi scene,” said Billy Linich, “more like Vadim with Brigitte Bardot than just Andy, the fag artist. That’s what happened when Edie came.”5

Above: Vogue, August 1965: Edie cuts an arabesque on her leather rhino

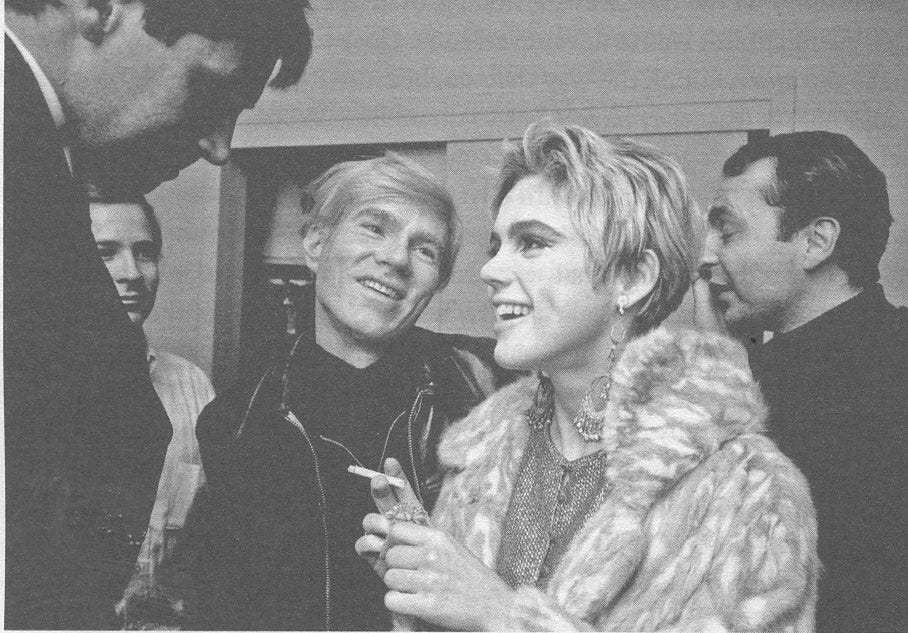

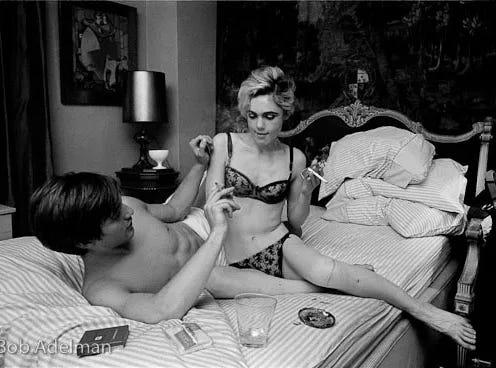

Below: With Factory hanger-on Gino Piserchio in Beauty #2, filmed in June 1965. Unlike the previous year’s notorious Couch, Beauty #2 was all foreplay, no out-and-out sex.

Evie definitely had cinema stardom in mind, but of the mainstream sort, not the underground buzz that Andy’s films generated. For her part, Edie was incapable of even the minimal technique that Andy asked of his actors. Edie was barely capable of day-to-day functioning, let alone memorizing lines (when there was a script) or showing up on time, if at all, for the rare rehearsals Warhol called. Edie and Andy were destined for a brief relationship. All but a few of her films were shot between April and July, 1965. Between August and December, she appeared in only two. Nineteen-sixty-five ended in thorough, mutual, disillusionment.

Meanwhile, opportunity beckoned, in Edie’s imagination at least, from another corner. An old friend of Tommy Goodwin’s, Bob Dylan’s charge d’affaires Bob Neuwirth, had a hunch that Edie might fascinate Dylan. Goodwin gave Neuwirth her telephone number, and Dylan called her.

They arranged to meet at Dylan’s favorite spot, the West Village bar the Kettle of Fish; according to Neuwirth, they had “a terrific time.”6 The pair turned up at an early 1965 party thrown by the art curator Sam Green, according to whom Dylan and Edie “spent the whole time in the corner.” Charmed by Edie, Green had nothing good to say about Dylan. “He was all about ‘I don’t need to communicate with you, man, you people are assholes.’”7

According to Warhol’s painting assistant and go-fer Gerard Malanga, Dylan and Edie were never lovers. As Malanga put it, “Dylan and his manager were interested in her as a possible matchup for a film with Bob, but when they found out she was a bundle of no talent, they dumped her.” They were a couple, insisted Danny Fields, and he had (or had once had) physical evidence: “Oh, indeed. Edie gave me the leopard-skin pillbox hat, which I kept for years.” (Fields’s reference, of course, was to Dylan’s song of that title.)

Dylan himself, one of the few public figures who topped Warhol as a master of the unforthcoming, evasive, and cunningly mendacious interview (and still does, bless his heart), told a reporter years later, “I never had that much to do with Edie Sedgwick. I’ve read that I have, but I don’t remember Edie all that well….I know other people who, as far as I know, might have been involved with Edie. Uh, she was a great girl. An exciting girl, very enthusiastic. She was around the Andy Warhol scene, and I drifted in and out of that scene.”8

Whether or not the famous pillbox hat ever existed, a reading of other Dylan lyrics strongly implies that Edie made a deep impression on him. You won’t get a better snapshot of Edie than the fog, amphetamine, and pearls of “Just Like a Woman,” and one of Dylan’s most virtuosic lines, “the ghost of electricity howls in the bones of her face,” from “Visions of Johanna,” uncannily echoes the art dealer Ivan Karp’s perturbed impression of the ever-agitated Edie: “There were sparks flying off her brain!”

The balance of power between Warhol and Sedgwick may have been heavily on Andy’s side, but it was Edie who severed the relationship. In the latter part of 1965, she was intent on signing with Dylan’s powerful manager, Albert Grossman. According to Danny Fields and, as we’ve seen, Gerard Malanga, the interest was, at least temporarily, mutual. “Grossman wanted to manage her as an actress, singer, girl of the year, whatever,” said Fields. “First get her, then do something with her. They courted her.” “I know that Bob Dylan expressed an interest in doing a film with Edie,” Bob Neuwirth told Edie’s biographer, Jean Stein.9

If it wasn’t already evident, the shift in Edie’s allegiances became clear to Robert Heide one December 1965 evening at the Kettle of Fish. Whether as a kiss-off to Edie or a last stab at working with her, Andy had commissioned Heide to write a screenplay for her, and invited Heide to the Kettle of Fish, ostensibly to discuss the script. Arriving, Heide was surprised to find Edie, alone. She was crying, “which was not all that unusual for her, and saying, half to herself, half to me, ‘I tried to get close to him but I can’t. He’s like an iceberg.’ She was choked up, in a state of anxiety.” Was she talking about Dylan, Heide wondered, or Warhol?

“And then Andy comes flying in,” said Heide, “with the dark glasses on, looking very natty in a blue suede outfit. He sat down next to me and across from Edie. I asked about my script. ‘Oh, we filmed that this afternoon,’ Warhol told him. Understandably irked, Heide kept his anger to himself. “Back then, the idea was that you were cool. You never showed your temper.”

The door flew open a second time, and in came Dylan, “with the hair and dark glasses and everything, pencil-thin, and sits down,” said Heide. “He’s very sullen. There’s this real tension going on. Nobody’s talking. After a while Dylan says to Edie, ‘Let’s split,’ and they went off.” The Kettle of Fish was Dylan’s hangout, and he could have showed up by coincidence, but it hardly mattered. Warhol had been jilted.

“I stayed there with him,” said Heide. Warhol expressed a bizarre wish. Mere weeks before, Freddy Herko, a severely disturbed, amphetamine-addicted dancer and occasional member of Warhol’s coterie, had committed suicide by leaping out of a sixth-floor window at a friend’s Cornelia Street apartment, the force of his leap nearly carrying him to the opposite sidewalk.

“Andy said he wanted to see the exact spot where Freddy had jumped,” Heide told me. “When we got there, he looked up, and looked at the street, and said, ‘I wonder when Edie will commit suicide. I hope she lets us know, so we can film it.’ I was in a little bit of shock about that, but I’d heard these glib remarks from him before,” said Heide. “I think he probably cared about Edie a lot. I think he was trying to sound detached. I think he was clenching his teeth.”

Whatever Warhol’s feelings for Edie, they were far from simple. In the film that he had asked Heide to write, “he had wanted me to write something in which Edie commits suicide,” Heide said. Heide had obliged; in Lupe, the film that Warhol had shot that afternoon, Edie’s character kills herself.

What to make of Warhol’s use of Edie here? In any event, she was out of his life. And of out Dylan’s, too. If Edie was in love with Dylan, she had a rude surprise in store: that November, Dylan had secretly married his girlfriend, Sara Lownds.

An aspiring filmmaker on the Factory scene named Chuck Wein saw himself as Edie’s protector and savior. For some time, Wein had wanted to make a movie with her, a narrative-driven, commercial work that Wein hoped would bring Edie mainstream stardom and free her from dependence on her awful family. It was to be based on the Charlotte Brontë novel Jane Eyre; judging by its title, Jane Heir, it seems likely to have been more spoof than serious drama. Wein and a co-writer, Genevieve Charbin, had drafted a scenario when Warhol soured on the project and called it off; Wein would thereafter blame Andy for what became Edie’s slide into self-destruction. I’ll give the perceptive Charbin the final say in the matter of Edie Sedgwick: “There’s absolutely no way that anything was going to save Edie Sedgwick, let alone a screenplay. She was very far gone, right from the beginning.” In and out of mental hospitals and occasional screen roles, Edie died in Santa Barbara in November 1971, aged 28, of an overdose of barbiturates. The county coroner was unable to decide whether her death was accident or suicide.10

In the insular world of hip mid-’60s culture, there were no coincidences. In 1966, Robbie Robertson, soon to become the Band’s great guitarist/songwriter, was backing up Bob Dylan on Dylan’s four-month world tour. During breaks, Robertson stayed at the chic but inexpensive Chelsea Hotel. So, as it happened, did Edie, her heavy-spending days in an expensive East Side apartment behind her. She had recently dated, and been dumped by, Bob Neuwirth “and she came by my suite one day,” Robertson writes in his memoir, Testimony, “ragging on him for his obnoxious behavior and asking if she could hang out for a while. She looked unique and gorgeous.” They met again, for dinner, later in ‘66. “Her recent visit with her family in California had not been pleasant,” writes Robertson, “and I’d already heard the whole sad story in my room as tears streamed through her mascara. Edie might easily have been dismissed as a ‘poor little rich girl,’ but I genuinely felt her pain. Her sorrow made me think that the coldness in her upbringing was terribly deep-rooted. Everybody hurts, but this was a lost soul.”

Tony Scherman and David Dalton, POP: The Genius of Andy Warhol (New York, 2009). All interviews by Scherman, unless otherwise indicated. Non-footnoted quotes are from Scherman interviews.

Scherman and Dalton, op. cit. p. 246

Nora Ephron, “Edie Sedgwick, Superstar,” New York Post, September 5, 1965, Section 2, p. 19

Scherman and Dalton, op. cit., p. 248

Ibid, p. 248

Jean Stein and George Plimpton, Edie: An American Girl (New York, 1994), p. 314.

Scherman and Dalton, op. cit., p. 290.

Dylan interviewed by Scott Cohen, “Don’t Ask Me Nothin’ About Nothin’,” Spin, December 1985.

Stein and Plimpton, op. cit., p. 283.

Coroner’s Register, Santa Barbara County, CA, November 16, 1971

This is the best essay on these relationships that I've read.