Duane Allman: Live in the Studio, Part 2 of 2

Session musicians, even the very best, play for anyone who's ready to ante up the money, including Sam the Sham.

6. Barry Goldberg and Mike Bloomfield, “Twice a Man”

Goldberg, a keyboardist, and Bloomfield, a celebrated guitarist, were boon companions from their high-school days in Chicago, blues lovers who, as members of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, backed up Bob Dylan when Dylan turned the folk music world on its ear by plugging in at Newport in 1965. Although Two Jews’ Blues, the 1969 album from which this song was taken, was a collaboration, only Goldberg’s name appears. Bloomfield was under contract to another label, hence his anonymity on the album, although he received credit when it was reissued in 1999. (You’ll also notice that the album jacket reads “Barry Goldberg…and,” indicating the presence of an unnamed partner.)

At some point in 1969 (no precise date is available), Goldberg and Bloomfield decided to cut an album, its title a facetious, and sophomoric, reference to their cultural heritage. Two Jews’ Blues was recorded at two studios virtually a continent apart: Paramount in Hollywood and little Quinvy Studio in Muscle Shoals, AL, whose sole hit was Percy Sledge’s 1965 multimillion-seller “When a Man Loves a Woman.” Goldberg and Bloomfield hired several members of the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section, including bassist David Hood and guitarist Eddie Hinton, and were delighted to include Duane Allman, who happened to be in the vicinity and available. To my mind, it is Allman’s presence on this album, playing electric slide guitar on just one song, “Twice a Man,” that gives Two Jews’ Blues its lasting significance.

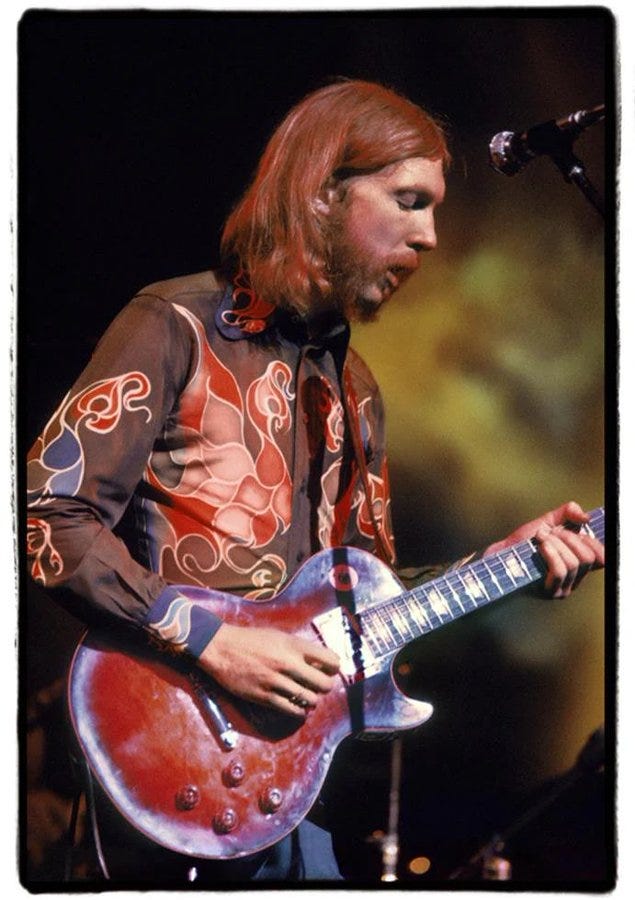

The front cover of Two Jews’ Blues. I take it that Barry Goldberg is on the left; I have no idea who is on the right. It is not Mike Bloomfield.

7. Sam Samudio, “Goin’ Upstairs”

Domingo “Sam” Samudio has had multiple incarnations as a rock & roller (and in other pursuits as well—when his musical career faded, he went to work as a commercial fisherman). In the early days—we’re talking 1961—Samudio donned a jeweled turban, outfitted his backup band in Near Eastern robes, and named them The Pharaohs. He himself was Sam the Sham, a self-directed gibe at his lack of skill as the band’s organist. In 1964, Sam wrote “Wooly Bully,” which sold three million copies and reached #2 on Billboard’s Hot 100. In 1966, Sam and the Pharaohs scored a second #2 Billboard hit, the mock-lecherous “Li’l Red Riding Hood.”

After a string of modestly successful Pharaohs singles, mostly novelty tunes, Sam struck out on his own, signing with Atlantic Records in 1971. Despite its stellar co-producers (Jerry Wexler and Tom Dowd) and Duane Allman’s scorching dobro and electric slide guitar on “Goin’ Upstairs” and four other songs, Sam Hard and Heavy went nowhere (although Sam’s liner notes won him the 1972 Grammy for Best Album Notes). At 88, Sam the Sham is still with us, though I doubt that he has another “Wooly Bully” in him.

8. John Hammond, “Shake for Me”

For fifty-plus years, during which he has recorded more than 30 albums, I have admired John Hammond’s prodigious guitar playing and his encyclopedic knowledge of the blues. At the same time, I have been never less than dismayed by Hammond’s minstrel-show imitations of the Black blues singers he admires so deeply.

In November 1969, John Hammond betook himself to Muscle Shoals Sound Studios to record Southern Fried, which was released in January 1970 on Atlantic Records. Duane Allman was not scheduled to participate, but ended up playing on four songs: “Shake for Me,” “Cryin’ for My Baby,” “I’m Leavin’ You,” and “You’ll Be Mine.” Allman’s two electric slide solos on “Shake for Me,” the album’s opener, are deeply satisfying. Here’s “Shake for Me,” written by the great Willie Dixon.

9. Johnny Jenkins, “Down Along the Cove”

Johnny Jenkins was a singer/guitarist/bandleader whose major claim to fame was that he hired a 21-year-old Otis Redding to do some singing but primarily to drive the band bus. One day in 1962, Jenkins and his band, the Pinetoppers, finished a session with 40 minutes to spare. Redding asked if he could use the time to record a ballad he’d written, “These Arms of Mine.” The song became Otis’s first big hit, selling 800,000 copies and leaving his boss far behind.1

Jenkins’s first album, and his only album for another 25 years, Ton-Ton Macoute! was recorded in 1969 and released in April 1970 by Capricorn, an Atlantic subsidiary. The album was originally intended to be Duane Allman’s first solo project. Allman, however, left to form the Allman Brothers Band after recording a number of instrumental tracks with three other soon-to-be Allmans: bassist Berry Oakley and drummers Butch Trucks and Jaimoe. When Allman and his confrères departed, Jenkins was invited to dub vocals over the instrumental tracks. 2

Ton-Ton Macoute! consists of highly, even wildly, dissimilar songs, including Dr. John’s “I Walk on Guilded [sic] Splinters,” Muddy Waters’s “Rolling Stone,” John Lee Hooker’s “Dimples” and Bob Dylan’s “Down Along the Cove.” It’s this last, from Dylan’s John Wesley Harding, that contains Duane’s finest playing on the album. His knifelike electric slide guitar is the song’s dominant voice, and he takes the song out with a magnificent, minute-long solo. In Ton-Ton Macoute! Allman provides a magnificent setting for a forgettable journeyman’s product. It’s the lot of the session player.

10. Delaney and Bonnie, “Come On In My Kitchen”

A&R Studios was a busy Manhattan recording studio, co-founded in 1958 by a then-very-young recording engineer, Phil Ramone, who would go on to prominence as one of the record business’s top producers, working with artists from Frank Sinatra to Madonna. After literally thousands of sessions, A&R closed its doors in 1989.

On July 22, 1971, Delaney and Bonnie played a show for a small audience at A&R. The Bramletts’ guests included Duane and Gregg Allman, King Curtis, and Little Feat’s percussionist Sam Clayton and bassist Kenny Gradney. I’ve searched hard for other participants, but with no luck. At the height of the counterculture era, ie. in 1971, activities as mundane as record-keeping were scoffed at.

The Bramletts’ show was broadcast live over WPLJ-FM. These were the days of free-form FM radio, when listeners to such FM stations such as WNEW (the longest-lived of the free-form stations), WPLJ, WOR, and WLIR took extended, often imaginatively planned, musical journeys, uninterrupted by commercials.

Duane Allman played on four songs with the Bramletts: "Goin' Down The Road Feeling Bad" (traditional), “Poor Elijah” and “The Ghetto” (written by the Bramletts with collaborators), and Robert Johnson’s “Come On in My Kitchen.” These and several other songs from the concert were released in 2017 as a bootleg Delaney and Bonnie album, Livin On The Open Road.

Two of the players at the A&R Studios show did not have long to live. Duane Allman died in a motorcycle accident on October 29, 1971, three weeks before his 25th birthday. King Curtis died on August 12, 1971, fatally stabbed outside of his Manhattan apartment building.

Here are the Bramletts and Duane Allman going to the source: Robert Johnson. Duane is playing acoustic slide.

Johnny Jenkins has advanced a second claim to fame, namely, to have influenced another flashy left-handed guitarist, Jimi Hendrix. Jenkins and Hendrix are documented to have played together in 1969 at Steve Paul’s Scene, a trendy Manhattan club of the day.

Jenkins’s album’s name has two derivations, one scary, the other deadly. Ton-ton Macoute is a mythical Haitian bogeyman. It was also the name that “Papa Doc” Duvalier gave his murderous secret police during Duvalier’s long tenure (1957-1971) as Haiti’s dictator.

Yes, they don't make that kind very often. Larry Coryell, Steve Gadd.

"Sui generis" is the best description of what Duane brought to the table.. They didn't make them like him B.D. (Before Duane) and they haven't made them like him A.D. (After Duane) either. One of a kind.