Bob Dylan's Brother from Mississippi: The Jim Dickinson Series, Chapter 2 of 3, "I'm an Agitator, a Troublemaker, I Don't Fit In."

"We’re past the period where music is very important culturally."

James Luther Dickinson was a kind, thoughtful, even idealistic individual often mistaken for a cynic. When we first spoke in 1987, I didn’t know Jim well (we were to become good friends), and I initially made that error: mistook his lack of illusions about the music business for cynicism. His response:

JD: I’m not cynical, the whole process is cynical. There’s a moment in production that’s dehumanizing and it’s inevitable, and that’s where the artist gets turned into hamburger meat. Lots of producers are in it just for that moment. I hate it. It’s my least favorite part, but it has to happen, because what you’re there to do is sell cornflakes.

“All artists come in thinking it’s their record. It’s not. It’s the company’s record. I don’t think anyone is honest enough to talk about it, ‘cause it’s the ugly part. The companies package hamburgers and the artist’s the meat and there can be no doubt about that, ever. I try to minimize it, but God, you take away so much from somebody when you cut a record on ‘em.

TS: Is there any way you try to redress that?

JD: I try to give them something back. I try to teach ‘em how to play in a groove, for instance. I worked hard on that with The Replacements, because they needed help. Cooder and Jim Keltner are continually debating, “Hmm, should we play a groove or not?” Just the idea of discussing whether you’re gonna play in a groove or not, to me that’s a little bizarre. I have to try not to groove.

I’ve had a running fight in Memphis with [jack-of-all-trades entertainer and deejay] Rufus Thomas. Rufus gives me that typical “White boys can’t play the blues” rap. My response, which it took me years to formulate, is “Maybe I don’t play the blues, but whatever it is I play, it’s because I was tryin’ to play the blues!” Actually, I can’t play either the blues or country music. I’d call what I play whorehouse piano. It sounds like I’m drunk, because I was drunk when I learned to play. I don’t drink now. Just play drunk.

With the young bands I work with, I tell ‘em stories. I’ll say, “Imagine the world before rock & roll….” Most of ‘em can’t, but you can tell when you’ve reached someone.

TS: Why “Imagine the world before rock & roll?”

JD: Because I want to make ‘em see they’re part of a dying breed. We’re all dinosaurs, me and them, because we’re past the period where music is very important culturally. The sine curve’s headin’ back down.

I try to at least make ‘em see the real implications of what they’re doing. ‘Cause it’s a fight between good and evil, as far as I’m concerned. It’s a moral issue, making a record. You’re committing it to the world, forever. If you do it wrong, it’s, it’s a sin.

TS: Why do you take it so seriously?

JD: It’s serious!

TS: Aww, it’s just a fuckin’ shallow business.

JD: Hell no it’s not, not to me! I’m not in business. I make records. What’s the definition of the word “record”?

TS: Product.

JD: Not to me. “Product” ain’t my word, it’s theirs, the people that sell it. And they never sell mine anyway, so fuck ‘em. Though the movie business makes the record business look like child’s play. Those movie guys are real wolves. You’re accountable to every asshole on earth. Makin’ records, that’s the coward’s way out.

TS: How would you characterize yourself to someone?

JD: I’m an agitator, a troublemaker, I don’t fit in. That’s part of why I’ve been picked up as a kind of guru to these young, post-punk bands. And I quit real well. I quit with a flourish. I make people realize, “Shit, he’ll quit.” Oh, I’m real good-natured, but I’m dead serious about what I do. Cutting records is no game.

TS: Do you ever talk to Ry Cooder about producing him again?

JD: No, that’s a sore subject. He produces himself now, and I don’t think he can. I don’t think anyone can. What I do as a producer is very hard to perceive. When the artist sees it, it almost never works. Like any kind of magic or sleight of hand—“Look over here, no, look over here”—that’s basically what I do. So Cooder, along with others who can remain nameless, after they experience my techniques they assume they can produce themselves. Which in every case is an incorrect assumption.

TS. So nobody can produce himself?

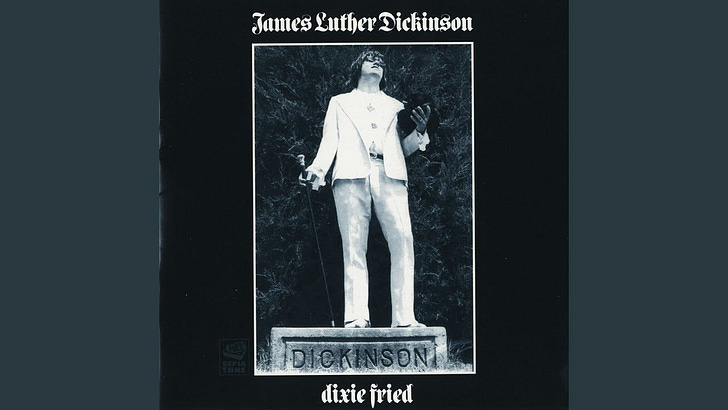

JD: Oh no, you can’t be on both sides of the glass at once. Look at the credits on my so-called artist album. [Dickinson is talking about his 1972 album Dixie Fried.] I didn’t produce it. Tom Dowd did. I purposely chose Tom Dowd because he was the person at Atlantic I got along with worst.1

One of the funniest, most imaginative tracks, with the least commercial potential, that Dickinson ever recorded, “Oh How She Dances,” from “my so-called artist album” Dixie Fried (Atlantic, 1972).

TS: What’s an example for you of a well-produced album?

JD: [Although Dickinson is critical of the Atlantic Records staff arranger and producer Arif Mardin, he goes out of his way to praise one Mardin production.] I must say, Arif made the record I’m by far prouder of anything else I played on at Atlantic, Carmen McRae’s Just a Little Lovin’. It’s with The Dixie Flyers, King Curtis, The Sweet Inspirations. Oh, it’s killer, killer! I’m playin’ piano like I can really fuckin’ play piano. Atlantic pulled the record back because Robert Flack was about to happen, and Carmen’s album was in the way.2

That’s paranoid theory, but I’ve talked to people who’ve said, yup, that’s what happened.

TS: Did the McRae record ever come out?

JD: Yes, but it’s very hard to get.

TS: What’s another great-sounding record?

JD: Howlin’ Wolf’s stuff with Sam Phillips. To me, Wolf’s a life force. Joseph Spence is real important to me. A musicologist-type guy who was dating a friend of my wife’s came over and played Spence’s Happy All the Time. I told him, “Buddy, you are not gettin’ out of my house with that record. You gonna give me that record.34

TS: Did he?

JD: Oh, sure. And there’s Folkways Records’ Country Brass Bands. You never heard that? It’s a lifetime experience! Cut in the middle of the night in a field outside New Orleans. Funky as anything you’ll ever hear. That and Spence enabled me and Cooder to communicate for 15 years! And Champion Jack Dupree’s Blues in the Gutter, that was central to my development.5

TS: Of your own productions, what’s your favorite?

JD: That’s like askin’ who’s your favorite child. Probably my favorite stuff never came out. Cooder always says, “The best stuff never gets recorded and the best sessions never come out.” Someone asked Cooder what his favorite session was. His answer was the Brenda Patterson session that I produced. Until it came out. ‘Cause when it was released [as Brenda Patterson, on short-lived Playboy Records in 1973], it had been taken away from me and Larry Cohn [a longtime Columbia Records executive] had ruined it. Perfect example of how your best stuff never comes out.6

TS: How about Big Star’s Third?7

JD: It’s up there. Of course, it wasn’t released for years; then it trickled out in England on one of those labels.

TS: Which?

JD: I don’t know, crooked bastards who never paid for anything.

Two from the quintessential cult album, Big Star’s Third, produced by Jim Dickinson. That’s Alex Chilton (to the left in the photograph) singing lead on both songs.

TS: Everyone talks about Third as a sort of descent, especially on Chilton's part, into psychosis.

JD: Well, it does have its sick moments. Maybe it was a little weird for when we did it, but what isn’t that’s significant? They’ve just made a CD of Like Flies on Sherbert. Now, that one really is sick.8

It’s interesting that some of the Warner’s people who hired me for the Replacements were the same ones who’d rejected Big Star’s Third. Jerry Wexler, Lenny Waronker, Karen Burns, they all turned it down. Karen especially read me the riot act: “This is perverted. You’re destroying Alex Chilton blah blah blah.” Ten years later, the Replacements come around and it’s Karen again: “Oh, Jim did such a wonderful job with Big Star’s Third.” They talk about it in these hushed tones. Some memories these people have.

TS: Didn’t Third pretty much take you out of the business?

JD: Yep.

TS: Railroaded?

JD: That’s a strong word. Let’s just say I was a bit too weird. And after Big Star Three I just didn’t see the point.

TS: Of what?

JD: Of making a record I believed in and thinking it would be promoted. I never really quit, but I went for sure pretty far underground. I cut records on Cybill Shepherd and on [the phenomenally talented but mentally unstable jazz pianist] Phineas Newborn on Newborn’s weekend leaves from the sanitorium. I scored a skin flick and a Maysles Brothers film and I had an all-girl band called The Clits with Alex Chilton’s girlfriend that almost went somewhere. And that was my Seventies. I didn’t do anything for real until Cooder brought me out to Hollywood. 9

TS: And today?

JD: The tricks are walkin’ the streets again! I truly think I’ve got a shot coming this time, or I wouldn’t have stuck around. ‘Cause producing really does take a lot out of me.

Tom Dowd was Atlantic Records's longtime staff engineer. In an earlier life, Dowd was an eighteen-year-old physics prodigy at Columbia when he was chosen to work on the top-secret Manhattan Project, America's effort to build the atom bomb. After it dropped, Dowd returned for his undergraduate degree in nuclear physics, but soon realized that he had nothing to learn in college: "They were teaching 1939 physics and I'd helped develop 1950 physics," he said. He dropped out to pursue his other love, music, and wound up in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, rock's, and possibly every other genre's, greatest-ever recording engineer. Dowd was also a top-tier producer who oversaw Derek and the Dominos’ Layla, The Allman Brothers’ Idlewild South, At Fillmore East and Eat a Peach, Eric Clapton’s 461 Ocean Boulevard, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Enlightened Rogues and co-produced several Aretha Franklin records, including Spirit in the Dark, which Jim Dickinson played on and discusses in Chapter Three.

Arif Mardin was another legendary Atlantic Records figure, the only trained musician on the label’s staff. From 1963 to 2001, Mardin composed hundreds, if not thousands, of arrangements for Atlantic and produced countless albums, although he never stopped composing his own, classical, music.

One of the greatest-ever blues singers, Howlin’ Wolf (real name: Chester Burnett) recorded for Sam Phillips in the days before Phillips started Sun Records. Wolf left the south for Chicago in 1952. His recordings, largely for Chicago’s Chess Label, and his hugely entertaining shows won him internation fame. He may have been Sam Phillips’s favorite artist, including Presley. Phillips famously said, "When I heard Howlin' Wolf, I said, 'This is for me. This is where the soul of man never dies.'"

Ry Cooder also worshipped the Bahamian guitarist Joseph Spence (1910-1984), whom Cooder has repeatedly cited as one of his two lodestars (the other is the Hawaiian slack-key guitarist Gabby Pahinui (1921-1980). For more on Spence and Folkways Records, for which Spence largely recorded, see my post of March 23, 2024, “The Asch Series, Part 1 of 3: The Bahamian Guitar Genius and Upstart Record Label that Changed Ry Cooder’s Life.”5

Blues in the Gutter (Atlantic, 1958) was the first of “Champion Jack” Dupree’s 34 albums, including collaborations. Dupree (1910-1992) was a blues and boogie-pianist and singer. (He was also a boxer who fought more than 100 bouts, hence his nickname.) Dupree was New Orleans-born. His father was from what was then the Belgian Congo and his mother was part African-American and part Cherokee. Orphaned at the age of eight, Dupree was sent to the Colored Waifs Home in New Orleans, where Louis Armstrong had earlier spent time. The orphanage/reformatory is where Armstrong learned to play cornet, and where Dupree taught himself piano. A lifelong traveler, he left New Orleans early to circulate throughout the Midwest, playing and recording with a number of major artists, including Big Bill Broonzy, Tampa Red, Scrapper Blackwell and Leroy Carr. Dupree finally moved to Europe in 1960, living in Switzerland, then Denmark, England, Sweden, and Germany, where he died. As a lyricist, Dupree had a way with words: "Mama, move your false teeth, papa wanna scratch your gums."

Brenda Patterson was a little-known but gifted Memphis-based singer who recorded three albums in the early-to-mid-1970s and was briefly a backup vocalist for Bob Dylan. On Patterson’s eponymous 1973 album for Playboy Records, Dickinson is listed as the producer on two tracks and co-producer on one, a cover of Georgia Gibbs’s 1955 classic, “Dance With Me Henry.” Playboy Records was a short-lived wing of the Hefner empire, headed by the music-business jack-of-all-trades Lawrence Cohn in between Cohn’s stints as an executive at Columbia Records. In 1991 Cohn shared a Grammy with the blues researcher/unscrupulous entrepreneur Stephen C. LaVere for Best Historical Recording for the long-delayed 1990 package Robert Johnson: The Complete Recordings.

Big Star was an early-’70s Memphis power-pop group led by the charismatic, self-destructive Alex Chilton. The band was a commercial failure with an outsized impact on younger musicians; Dickinson’s production of Big Star’s third and final album and his later work with Chilton were largely responsible for his high status among post-punks. The critics on Big Star: "One of the most mythic and influential cult acts in all of rock & roll” (Allmusic). Rolling Stone: Big Star created a "seminal body of work that has never stopped inspiring succeeding generations." The band’s three albums are all in Rolling Stone’s “500 Greatest Albums of All Time” list. The third album was recorded in 1974 but unreleased until the minor record company PVC put it out as Third in 1978. In 1987, the equally obscure English label Dojo Records released it as Sister Lovers.

Big Star was the second episode in Chilton’s career. As a teenager in the late-’60s, he was the lead singer for the Top 40 band The Box-Tops, who scored a #1 Billboard Hot 100 hit with “The Letter” and two other highly successful songs, “Cry Like a Baby” and “Soul Deep.”

Dickinson produced Alex Chilton’s 1979 solo album Like Flies on Sherbert, in Dickinson’s words “the ugliest thing I ever did.” It was released by Memphis’s Peabody Records in 1979 and in the same year in England by Aura Records. Major labels may have lusted after the Box Tops; they wanted nothing to do with Big Star or Chilton’s solo work.

Dickinson wrote the music for Running Fence, a 1978 collaboration by the celebrated documentarians the Maysles Brothers with Charlotte Zwerin that follows the years-long effort of the artists Christo and his collaborator and wife Jeanne-Claude’s to erect a 24.5-mile “fence” of nylon fabric in Sonoma and Marin counties in Northern California. The Maysles and Zwerin also made Gimme Shelter (1970), which documents the final weeks of the Rolling Stones’ 1969 U.S. tour, which ended with the disastrous Altamont Festival.

Next: Chapter 3 of 3, “Famous Animals I Have Known”