Bob Dylan's Brother From Mississippi: The Jim Dickinson Series, Chapter 1 of 3, "Good Production Borders on the Criminal"

"When I work with an artist, I want something extra, magic: their souls, damn it." Thus James Luther Dickinson: producer, session musician, solo artist (1942-2009).

In February 1998, Bob Dylan won his first Album of the Year Grammy. The fact that Time Out of Mind was Dylan’s 40th or so album made the award almost an insult. In any case, in his onstage thank-yous, the singer pulled an unfamiliar name out of his hat, thanking “Jim Dickinson, my brother from Mississippi.”

“Who?” wondered most of the audience, live and in TV Land. A bit of backstory: Evidently unhappy with the musicians that Time Out of Mind’s producer, Daniel Lanois, had chosen for the session, Dylan invited Dickinson and Dickinson’s colleague of decades, the great session drummer Jim Keltner, to join the proceedings. Dickinson ended up playing piano, Wurlitzer electric piano, and pump organ on eight of the album’s 11 tracks. “Jim Dickinson deserves credit for profoundly shaping Time Out of Mind,” writes the critic John Lewis. “Dickinson became a key Dylan ally and confidant during the recording process and infused the record, tangibly and intangibly, with soulful ballast.”

In his Chronicles, Volume One, Dylan recalls feeling out of kilter at the Time Out of Mind sessions. “I’d been thinking about Jim Dickinson and how it would be good to have him here.” So he brought him there. “Jim,” Dylan writes, “had manic purpose.”

I’m not sure what “manic purpose” is. What Dickinson had, to quote John Lewis again. “was an uncanny knack for turning up at key points in rock history as a transformational presence.” The Rolling Stones’ 1971 album Sticky Fingers, for instance, on whose ballad “Wild Horses” Jim Dickinson plays piano. Dickinson was in the studio as a guest and had never heard the song before, yet his understated, quietly decisive playing shows that he had quickly grasped exactly what “Wild Horses,” a great Stones classic, needed. “Dickinson,” says Keith Richards in his memoir, Life, “was a beautiful piano player.”

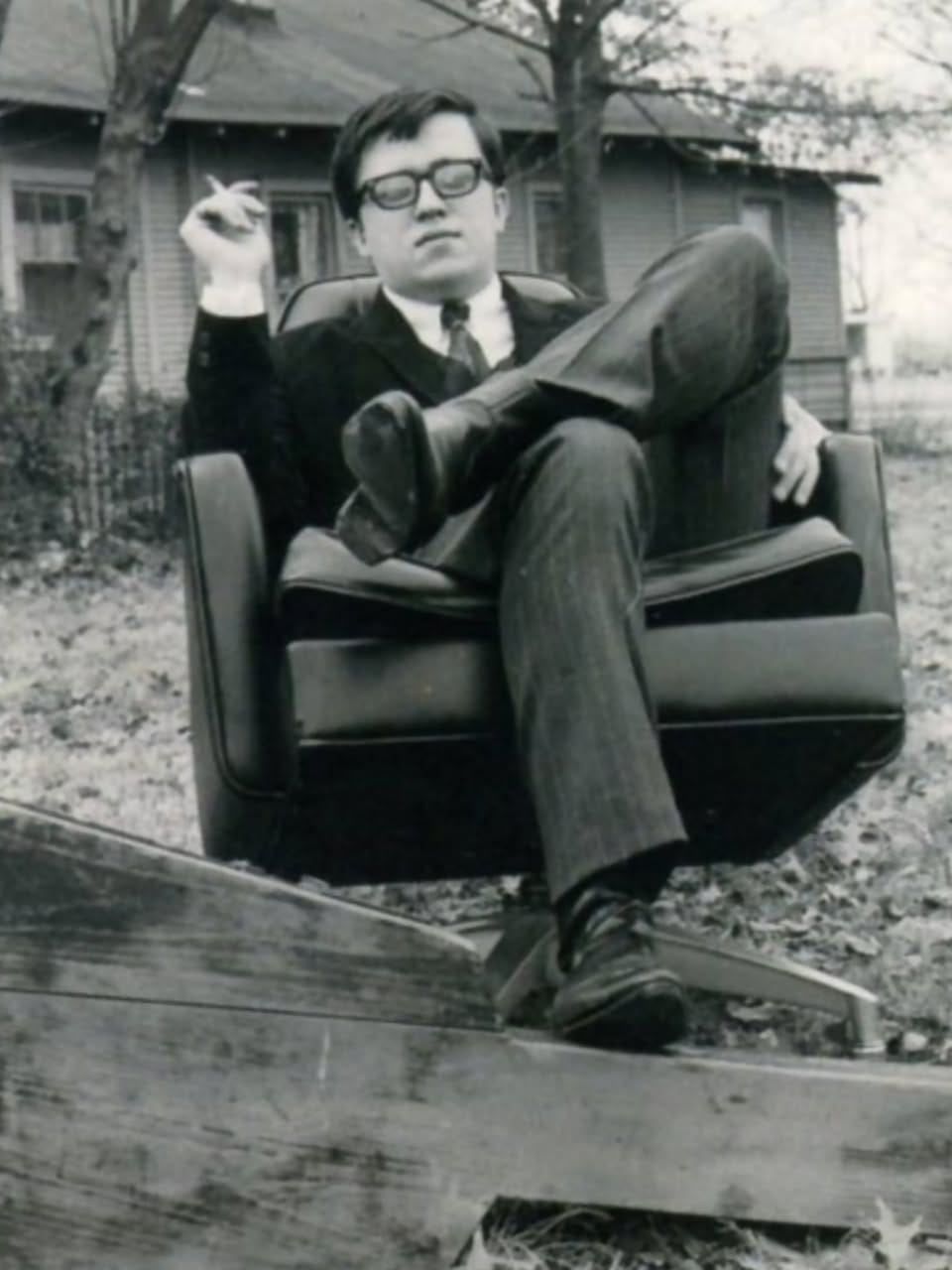

“With no idea what kinda shit was about to go down”: the artist in his younger days.

Dylan and the Rolling Stones are not the only major artists with whom James Luther Dickinson worked during his four-decade career. Jim and the great Ry Cooder had a long, productive partnership. Dickinson co-produced Cooder’s second and third albums, Into the Purple Valley and Boomer’s Story (both released in 1972) and played on 10 other Cooder albums. When Ry was hired to write his first movie score, for Walter Hill’s The Long Riders (1980), he invited Dickinson to join him in a collaboration that had, as of 1987, lasted through nine soundtracks. With Cooder and John Hiatt, Dickinson wrote the much-recorded “Across the Borderline,” the theme song to the 1982 Jack Nicholson movie The Border.

I knew Cooder before I knew Dickinson. When I asked the guitarist to describe his friend, Cooder said, “He’s this genius from down around Memphis.”

Dickinson never merely produced or played; he taught. The Replacements, for instance, whose 1987 album, Pleased to Meet Me, was a Dickinson production. Jim Dickinson loathed the business side of record-making as deeply as any punk rocker, but he was bitterly aware that especially for a young band, success meant compromise. If The Replacements wanted to escape the commercial trough they inhabited as a minimally selling cult band, he told them, they were going to have to abandon their trademark sloppiness. The band’s leader, Paul Westerberg, absorbed Dickinson’s message. His bandmates did not, playing their customary wrong notes until Westerberg screamed at them, “Look, we do it Jim’s way or we keep playing basements for fifty creeps spitting on us.” The record was not only an artistic, but a commercial, breakthrough, selling 300,000 copies—not exactly a hit, but by far the band’s bestseller. Dickinson’s, too, although he’d been perfectly comfortable operating under the commercial radar. “I’ve never produced, played on, ridden a go-kart through the neighborhood when someone was cuttin’, a Top Ten single,” he told me in 1987. “Of which I’m almost proud. I don’t sell cornflakes. I tell my potential victims, “A hit’s something from baseball; singles pick each other up in bars.” 1

Like many post-punks, the Replacements held the ‘70s Memphis band Big Star and its frontman, Alex Chilton, in high esteem. One of Pleased to Meet Me’s songs is titled “Alex Chilton,” and Chilton himself plays guitar on another, “Can’t Hardly Wait.” Dickinson produced Big Star’s final album, Third, like its predecessors a commercial disaster with an ardent cult following. Dickinson also produced Chilton’s first solo album, 1979’s Like Flies on Sherbert. Dickinson and Chilton outdid themselves on this one, which even Chilton’s fans despised.

When Dickinson decided that The Replacements’ “Can’t Hardly Wait” needed horns and strings, anathema to a bunch of post-punkers, he waited until the band had left Memphis before dropping in the overdubs. He knew they’d be enraged. “My first obligation,” Dickinson told me, “is to the project. My second is to the artist.”

When Dickinson contributed to a hit, it was as a player. The Miami-based session band The Dixie Flyers, with Dickinson on piano and occasional guitar, backed up Aretha Franklin on much of her 1970 album Spirit in the Dark. The album’s “Don’t Play That Song,” was not only a #1 R&B hit, but won Franklin a Grammy (Best Female Rhythm & Blues Performance).

Dickinson was a solo artist, too. Dixie Fried (Atlantic, 1972), which Dickinson referred to as “my so-called artist album,” was his only solo venture until 1997, when he began cranking out albums, many of them with his sons, Luther and Cody, who formed the core of the much-admired band The North Mississippi Allstars. Dixie Fried hardly sold, but won the admiration of the cognoscenti. In 1977, the author and critic Nick Toaches called the album “one of the most bizarrely powerful musics of this century." I reluctantly take exception to Tosches’s extravagant praise. Dixie Fried is only intermittently good; Jim Dickinson did his best work elsewhere.

Pleased to Meet Me was the peg of sorts (the album had been out for several months) for the Dickinson profile I contributed to Musician magazine’s November 1987 issue. This interview is the article’s raw material, vigorously edited for length. (In those days, I habitually over-interviewed. I still do). The interview is underway as you begin reading, with Dickinson describing his physical surroundings. We spoke by phone. I employed a tactic that would have gotten me fired from The New York Times, that is, I had Dickinson provide me with enough physical detail so that I wrote the article as an eyewitness, as it were, sitting with Jim in his house in the woods of northwest Mississippi.

TS: I’m trying to get a sense of how rural your home is.

JD: Whoa, it’s out there! I’m on a lake four or five miles from Eudora, which is just a crossroads and a bait shop. Hernando [where Dickinson and his family moved from the Memphis area in 1985] is five crossroads away. It’s all DeSoto County. Next county over is Tunica.

TS: You and your wife have two sons, right?

JD: Right, Luther and Cody. They’re 14 and 11. Luther plays the guitar solo on “Shooting Dirty Pool” on the Replacements album. Him braggin’ about it at school kind of blew my cover around here. It’s definitely heavy redneck territory. You disapprove of your neighbor, hell—burn his house down. People think I’m an old biker or something. I don’t want to let ‘em know what it is I’m up to. 2

TS: Have you ever cut records at home?

JD: My place is too small, but I’m headed that way. One of the things I regret least in my quote unquote career is working with Arlo Guthrie. When we showed up for Arlo’s session, it was just his home. I was playing piano and looking out Arlo’s window when the first snow of the year fell, and I thought, “Wow, if I could only record like this.” I’ve been trying to put that together since. Actually, on “Boomer’s Story,” I cut Sleepy John Estes at my house in Collierville. I tied a microphone to the dining-room chandelier. That was our vocal mike. When I recorded Cooder in L.A., Lenny Waronker said, “Why can’t we get this stuff to sound like it did in Tennessee?”34

Without working with Arlo, I would never have understood Alex Chilton. On “The City of New Orleans,” it’s Take Three that you hear on the radio. Everyone in the room knew that if we went to five, six or seven, we’d really have something special. Arlo wouldn’t let us. He didn’t want it to be great, he didn’t want to jump into real success. He holds himself back from popping through, like success is a membrane and you’ve got to do certain things once you’ve popped it. Waylon Jennings has made a career of that. “Naw, I don’t wanna go that far.” I watched Alex Chilton cut his most recent album, High Priest (1987). It was typical Alex: he cut thirty songs and released the worst ten. (There will be more on Chilton in Chapter 2).

TS: What do you see out your window?

JD: Nothin.’ Water, the occasional fishing house. That’s what I want. After my stint in Miami Beach, I didn’t want to look out the window and see anything. It’s the only way to recharge. Plus it’s the stuff that it’s all about. It’s the dirt and water and sky.

TS: The stuff that what’s all about?

JD: The music.

TS: The music you love.

JD: The music my whole life’s been about. I was born in Little Rock but we moved to Memphis in 1948. I grew up in East Memphis when it was more rural than suburban. This was still way pre-rock & roll, though you could hear the germ of something talking to you. In 1948, Dewey Phillips had just gone on the air. WHBQ Memphis, out of a studio they built in the Gayoso Hotel. 5

Dewey Phillips was a man unlike any you’d ever seen. Dewey Phillips was a Martian!

TS: What do you mean?

JD: I mean he related to the world like an alien who’d just landed in a saucer. He was this crazy, wild-eyed nut! I was hip to black radio, but Dewey Phillips played black music on a white station, a lot, which you didn’t do. Nor did a deejay work drunk, which Dewey also did.

In ‘54, Dewey broadcast the first Elvis record, “That’s All Right/Blue Moon of Kentucky.” After that, it like a new comic book every month. The British Invasion was something like that. You’d sit there anticipating the next Elvis, the next Jerry Lee. You’d hear “Red Hot”, by Billie Lee Riley With His Little Green Men, Jerry Lee Lewis on piano, and you’d think, “My God, this is the ultimate rock & roll record—but no, here comes Jerry Lee with “Whole Lotta Shakin”! Oh, killer! 6

TS: So all this is making a pretty huge impression on you?

JD: Sure, I had a guitar by ‘56.

TS: When did you first want to be a producer?

JD: As soon as I knew such a thing existed.

TS: What do you do when you produce?

JD: Nothin’. OK, I’ll bite. Actually, “nothin’” is truer than you think. What I do is almost all psychodynamics. Sometimes it’s just creating the right diversion. With [the tense, high-strung] Cooder, it’s almost always that. Stop the artist from thinking, so his subconscious can do the right thing. The first time I worked with Quinton Claunch was on a James Carr session that Quinton produced. I saw some real peculiar behavior, and it wasn’t just James. Quinton didn’t like what [bassist] Tommy McClure was playing, but he had no idea what notes to tell Tommy to play. Even if he had, Tommy wouldn’t have played ‘em, too stubborn. So Quinton walks over by McClure and just stands there looking out the window and rattling the change in his pocket. Before long, Tommy starts playing something that works. Now, that’s great production. Without a word, with this little charade, Quinton gets Tommy to come up with the perfect bass line. It took me a long time to figure out what Quinton was doing. Who’s this goofy guy rattling change, what in hell’s going on here? But I learned that Quinton always kept change in his pants. 7

James Carr’s “Dark End of the Street, “one of the most unforgettable songs of the soul era.”

TS: What holes have you got as a producer?

JD: Hmm…very few. Danny Stuart says I should assert myself more. But as I’ve just said, an essential part of producing is not conspicuously asserting yourself. I just can’t be heavy-handed. I’ve been on the other side of the glass [ie. as a player] too many times, and I know the reaction I had to it.8

TS: What’s your trump card, your strength?

JD: Boy, I don’t know. Well, I know a lot of the tricks. And by participating as a player, I’ll make the session better. Larry Knechtel, there’s the best session keyboard player in the United States, he’s everywhere from “Bridge Over Troubled Water” to the “Hill Street Blues” theme. He’s by far my superior as a player. But when I come to a session, I bring more with me than technique. I can translate between producers or engineers and musicians, who often don’t understand what the hell the people in the control room are telling them. We are talking about a folk music, because it’s not written down. It has to be communicated verbally.

TS: I get the impression that you go home and think, “How am I going to work with this artist?” That you’re constantly evolving strategies, tricks, techniques. Not many producers do that, not nowadays.

JD: No, they don’t. And I also don’t think they’re producing. Most of the English school of producing—it’s packaging. In any other so-called artistic business—books, jazz, classical music— what’s created is considered a unique accomplishment. In our business, it’s a flat black disc with a hole in it. That’s not the way I think about it. I want something extra, magic—their souls, damn it. Good production borders on the criminal.

(Above:) Dickinson contributed heavily to Ry Cooder’s soundtrack for the 1982 Jack Nicholson movie The Border. He wrote “Texas Bop,” sang it, and played his trademark “whorehouse piano,” as he called it, including trading solos with Cooder, not an undertaking for the faint of heart.

(Below): The anti-anthem “Mighty Gun,” from Green on Red’s 1987 album The Killer Inside Me, a Dickinson production. Despite, or because of, its rough edges, the song is a rock masterpiece, anticipating today’s revisionist view of American westward expansion.

Pleased To Meet Me was the sixth album by the Minneapolis-based post-punk band The Replacements, led by the talented songwriter Paul Westerberg. Like many post-punks, the Replacements idolized an earlier Dickinson client, the band Big Star’s frontman, Alex Chilton, whom the Replacements asked to play guitar on Pleased To Meet Me’s song “Can’t Hardly Wait.” Another Pleased to Meet Me songs is actually titled “Alex Chilton.” Lyrics such as “Children by the millions sing for Alex Chilton when he comes 'round/They sing I’m in love with that song” are highly ironic—Chilton’s audience was minimal.

Now 52, Luther Dickinson, a guitarist of note, and his brother Cody, 49, form the core of The North Mississippi AllStars, the band the Dickinson brothers formed in 1996. The Allstars have been nominated for three Grammys and won the Blues Music Award for Best New Artist. They’ve released 14 studio albums and six live albums, a long-lived, highly regarded band. From 2007 to 2011, Luther divided his time between the Allstars and The Black Crowes, appearing on three of the latter’s albums.

The major Memphis-area bluesman Sleepy John Estes (1903-1977) appeared on two tracks of the Dickinson co-production Boomer’s Story.

Waronker, Boomer’s Story’s other producer, was head of A&R at Warner Brothers Records from 1970 to 1982, president from 1982 to 1994, and co-chairman of DreamWorks Records for a number of years, returning to Warner Brothers as a consultant in 2010. Waronker was the rare record-biz executive who actually knew how to make a record, producing albums by, among many others, Randy Newman, Paul Simon, Brian Wilson, Maria Muldaur, and Rickie Lee Jones. A Waronker production, Arlo Guthrie’s album Hobo’s Lullaby contained Arlo’s version of Steve Goodman’s song “The City of New Orleans”: Arlo’s only top-40 hit, reaching #18 on Billboard’s Hot 100 singles chart. Dickinson plays the lovely piano accompaniment on “City of New Orleans,” including the brief piano solo that ends the song.

Highly eccentric, unstoppably energetic, and incurably alcoholic, the Memphis disc jockey Dewey Phillips had a great ear for new sounds and an utter disregard for convention. In July 1954, Phillips was the first deejay to play Elvis Presley: Elvis’s first record, “That’s All Right”/"Blue Moon of Kentucky,” and conducted an on-air interview with the painfully shy 19-year-old. Phillips also introduced his mostly white audience to Black R&B and gospel artists. When WHBQ adopted a Top 40 format in 1956, Phillips was fired. Drinking increasingly heavily, Phillips moved from one minor station to another. He died in 1968, only 42.

It was Sam Phillips (no relation) who brought Elvis’s “That’s All Right” to Dewey Phillips. Sam recorded Howlin’ Wolf, among others, at his Memphis Recording Service before founding Sun Records in 1954, where he recorded Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash, Charlie Rich, B.B. King, Roy Orbison and Carl Perkins. In 1956, Phillips sold Elvis’s contract to RCA Records for a then-record $35,000. The definitive Phillips resource is Peter Guralnick’s Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock ‘n’ Roll (2015, Little, Brown).

James Carr had several medium-sized, and one major, hit for Goldwax: “The Dark End of the Street (1966),” which Guralnick calls “one of the most unforgettable songs of the entire soul era.” Carr’s voice, Guralnick writes, “could… soar majestically, suggest peaks of emotion, yield layers of meaning, and convey subtleties of understanding and interpretation” that few singers could approach. Carr’s career was impeded and shortened by mental illness—he was severely bipolar, most likely undiagnosed. Although Carr had periodic, brief comebacks, by 1969“it was almost impossible to get a session out of [Carr],” according to Quinton Claunch. “One time in Muscle Shoals I got one song out of a six-hour session,” Claunch told Guralnick. “He would just sit there on the stool, not say a word, and just look at you. And then three hours later sing the song all the way through.”

Singer/songwriter Danny Stuart co-founded the The Serfers in Tucson, AZ in 1979; in 1980 the band became Green on Red and moved to L.A. In 1983 they signed with Slash Records, Warner Records’ crucial indie-rock label that released albums by X, The Blasters, Los Lobos, The BoDeans, The Del Fuegos, and many others. In 1985, singer/guitarist Chuck Prophet, unlike Stuart still active today, joined Green on Red. An avid fan of the noir novelist Jim Thompson, Stuart named the band’s third album, The Killer Inside Me (1987) after a Thompson novel. Dickinson produced it and co-produced Green on Red’s next, Here Come the Snakes (1989). Stuart’s left-wing convictions informed songs like “Mighty Gun,” probably The Killer Inside Me’s finest song, its refrain “And that’s the way the West was really won/Plenty of cheap labor and the mighty gun. Stuart disbanded Green on Red in 1992.

Love this! I’m Harrison, an ex fine dining line cook. My stack "The Secret Ingredient" adapts hit restaurant recipes (mostly NYC and L.A.) for easy home cooking.

check us out:

https://thesecretingredient.substack.com

Nice article, Tony. I never heard of this guy, but his role in Time out of Mind caught my attention because it’s my all-time favorite Dylan album. Maybe Dickinson will provide an enigmatic clue

as to why. Many priceless vignettes captured in your story, and the footnotes read like a bonus article. I enjoyed all the youtube links, too. Thanks, WW