Al Kooper Before, During, and After "Like a Rolling Stone": Humor, Taste, and Chutzpah

The ultimate rock & roll survivor tells the story of the so-called Brill Building Pop era: "Carole, Barry, and Cynthia were high echelon. I was low echelon."

Before the Beatles and Bob Dylan diminished their relevance (demolished is a more accurate word), three midtown Manhattan buildings dominated the music industry in America and beyond. These were 1619, 1650, and 1697 Broadway. Between the late Fifties and mid-Sixties, when the venerable business of music publishing (the care, feeding, and exploitation of songwriters) adapted itself to rock & roll, two of the above addresses were of far less significance than the third. 1697, between 53rd and 54th Streets, consisted largely of fly-by-night music publishers, record labels, recording studios, and rehearsal spaces. Its main distinction was as the home of the Ed Sullivan (then David Letterman, now Steven Colbert) shows. 1619 was the only one of the

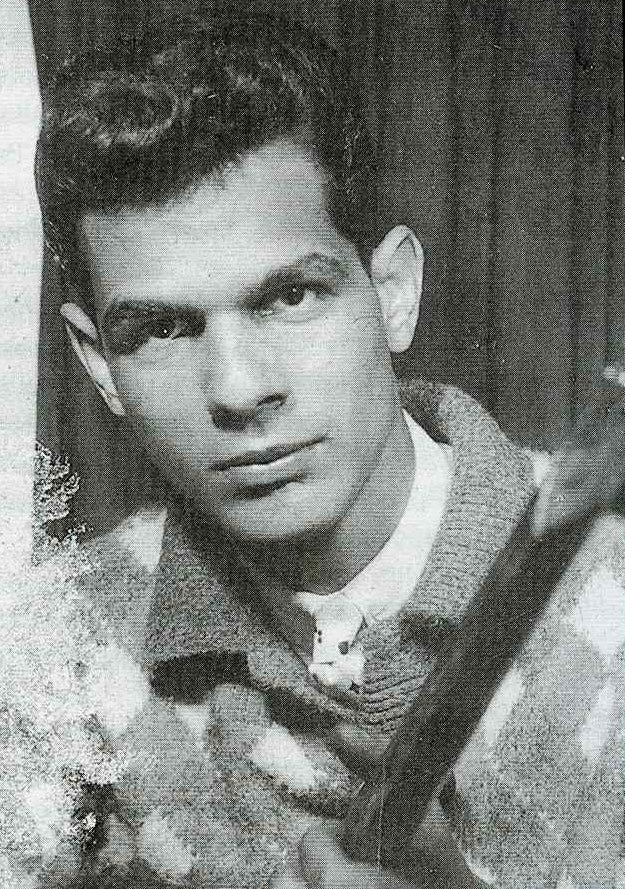

Portrait of the artist as an outerborough punk, ca. 1960

buildings with a name. Once music publishing’s flagship, by 1960 the Brill Building was a shell of its former self. In an irritating misnomer, the early Sixties music that welled out of all three buildings is everywhere, and erroneously, called “the Brill Building Sound.” The Brill Building was indeed the hub of the music business—from 1935 to 1955, when songwriters wore fedoras, suits and ties. I’m going to take the corrective step of referring to early Sixties, midtown-Manhattan-based rock and & roll not as “the Brill Building Sound,” but as Neo-Tin Pan Alley, the successor to Jimmy van Heusen’s, Hoagy Carmichael’s, and Mills Publishers’ milieu (Irving Mills managed, published, and ripped off Duke Ellington for a dozen years): the original Tin Pan Alley. (It actually wasn’t; see footnote1 ).

The Brill Building continued to harbor a few major Neo-Tin Pan Alley players, including the songwriters Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller and their jumping record label, Red Bird, and the songwriting duo of Burt Bacharach (music) and Hal David (words). Bacharach may well be the finest composer that the era produced. His and David’s muse was Dionne Warwick, in whose first, 1962, hit, “Don’t Make Me Over,” Bacharach’s trademarks— unconventional chords and off-kilter time signatures—are already on full display. “Bacharach destroyed me,” Kooper said. “Changed my life. I’d never heard anything like it. In ‘Don’t Make Me Over,’ he played a B-minor in the key of C. No one had ever done that before. That’s an amazing chord change.”2

Bacharach/David and Leiber/Stoller’s brilliance notwithstanding, the rise of rock & roll songwriting and of 1650 Broadway, on 51st Street, was simultaneous and symbiotic. 1650 was where the action was. “I’d have to say,” Kooper writes in his informative, and very funny, Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards: Memoirs of a Rock ‘n’ Roll Survivor, “that the majority of the music business from 1960 to ‘65 was at 1650,” most of it, moreover, in a single company: Aldon Music. During those years, Aldon’s co-owner and prime mover, Don Kirshner, whom Time Magazine dubbed “the Man with the Golden Ear,” saw to it that Aldon became what Kooper called “the hottest song-publishing concern of the early sixties and perhaps of all time.”

Kirshner’s stable of writers, cranking out #1 hits in their industry-standard soundproofed cubicles, included Carole King, Gerry Goffin, Barry Mann, Cynthia Weil, and Neil Sedaka, a coterie which, as Kooper said, “[had] the top of the charts padlocked.” If King and Al Kooper happened to share a 1650 elevator, nothing more than a nod, if that, was exchanged. “They were high-echelon. I was low-echelon,” Kooper told me in 1991, when I interviewed him for a book on Neo-Tin Pan Alley. My book remains unfinished, but its ghost survives in the form of the many interviews I conducted with the district’s inhabitants, including Kooper, the great session pianist Paul Griffin,3 and the brilliant, self-destructive label owner George Goldner, another 1650 tenant. 4 You’ll find an especially rich portion of the Kooper interview at the bottom of this piece.

The competition, except there was no competition: “Aldon Music was the hottest song-publishing concern of the early Sixties and perhaps of all time,” said Al Kooper. These three—songwriters Barry Mann (at the piano), Cynthia Weil (behind Mann, left), and Carole King (behind Mann, right)—and their Aldon colleagues, most of them in their early 20s, if that (Carole King was 17 when she married Gerry Goffin, who was 20) “had the top of the charts padlocked,” Kooper told me.

Al Kooper was in the rock & roll business before he was in the eighth grade, playing guitar and piano in outerborough bands (Kooper grew up in Queens) with names like The Aristo-Cats and the Casuals. At 14, he joined the one-hit-wonder Jersey band the Royal Teens. The song, which went all the way to Billboard’s #3 in 1958, was “Short Shorts,” of which Sha Na Na would have done a credible version. Kooper escaped embarrassment; “Short Shorts” was cut before his tenure.

By 1958, Kooper was haunting 1619, 1650, and 1697. He and two fellow songwriting neophytes daily made the rounds of all three buildings, performing their latest collaboration for one jaded publisher after another. “It was like the Jolson story,” said Kooper. “If we wanted to eat, we really had to give some performances.” Their writing regimen was a song a week. Nine out of 10 were rejected; those that sold went for $300, plus, in rare instances, a few bucks in royalties. (The chanteuse Keely Smith, a member of an earlier musical generation than Kooper’s, cut one of their songs, which she sang on the Ed Sullivan Show, to Al’s parents’ delight.

Al began to supplement his songwriting income with recording-session gigs, primarily on guitar. He was not much of a player, but his lack of technique worked in his favor; in the early Sixties, a lot of producers wanted a “street,” ie. raw, sound. Kooper, who was still a teenager, dreaded playing sessions with the top-tier, jazz-trained players who still comprised a significant percentage of New York studio musicians: King Curtis, for instance, the virtuoso tenor saxophonist who’d defected from jazz to make big money as a bandleader and perhaps Manhattan’s most vaunted session player. To the Curtises of the district, Kooper’s presence was an insult. “It was as if Blood, Sweat and Tears [Kooper’s sophisticated late-Sixties band] had hired Sid Vicious.” In our interview, Kooper’s anguish at recalling his borderline sadistic treatment at Curtis’s hands is palpable. “I don’t know if it was a black-white thing or a young-old thing. Probably some of both. But I used to puke when I got to a session and Curtis was there. Curtis just fucking hated me.

“But the guy that hated me the most was a drummer named Herbie Lovelle. He cost me playing on B.B. King’s [1969 megahit] ‘The Thrill is Gone.’5 He just vibed me out. Shut me down. I was booked for four days, and after the first night I called the producer and said, ‘I don’t think I should be on these sessions.’ Which I’d looked forward to for two months.”

Back to the early Sixties. Improving apace as a writer, Kooper impressed one of 1650’s higher-class occupants. A songwriter who’d written five #1 songs for Elvis, Aaron Schroder branched out and founded Musicor, a record label, to which he signed, among others, the gifted singer/songwriter Gene Pitney. (Pitney’s “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” and “24 Hours From Tulsa” are first-rate pre-Beatles rock & roll. Pitney also recorded a marvelous Musicor album with the great country singer George Jones.) Moving into publishing, Schroeder prospered, hiring a staff of songwriters, including a teenaged Randy Newman, whom Kooper recalls as having the limpest,, most repellent handshake he’d ever experienced.

Schroeder began tossing the occasional plum assignment Kooper’s way. When he asked Al and his partners to write a song for the great R & B vocal group The Drifters, they jumped at the chance. Kooper, especially, slaved over it. The Drifters passed. The song was eventually picked up by the Los Angeles producer Snuff Garrett, who, seeing an opportunity to capitalize on a famous name, gave it to Jerry Lewis’s son Gary, minimally gifted singer and drummer. Kooper had no inkling of these developments, and when Schroeder proudly played him Gary Lewis and the Playboys’ “This Diamond Ring,” which Schroeder considered a surefire hit, Kooper was disgusted. “They’d removed the soul from our R & B song and made a teenage milkshake out of it.” When “This Diamond Ring” toppled the Righteous Brothers’ pop masterpiece “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling” from Billboard’s #1 slot, Kooper was not elated, but embarrassed.

The public’s tastes, meanwhile, were shifting. “The Beatles were giving Aldon the bum’s rush,” writes Kooper, “and an unholy alliance between Bob Dylan and marijuana was fucking with my head in a fierce way.” The Beatles were working on Revolver, which on its 1966 release would set a new standard for rock albums. Whether he denied it or not, no doubt horrified at the thought of being considered an Artist, Dylan’s lyrics were becoming richer, denser, more oblique, and he was about to trade his Martin acoustic for a Fender Stratocaster. Assembling a band, whose personnel shifted almost daily, Dylan was writing and singing songs that were a far cry from “Blowin’ in the Wind—“Subterranean Homesick Blues,” for instance, Dylan gone electric, if tamely.

By 1964, which began with the Beatles inducing hysterics in hordes of barely pubescent girls, and certainly by 1965, Aldon Music and 1650 Broadway were going down the tubes. “The Beatles—that was the end of everything,” Kooper said. “And Dylan. They destroyed the whole thing,” that is, Neo-Tin Pan Alley. “Because they were anti-formula. The Beatles were writing such original music and Dylan such original lyrics that they completely changed the music business. Fortunately, I was able to go in their direction.”

Only a few musicians survived the Beatles/Dylan holocaust (a number of studio players kept their jobs), and only the most resourceful of these flourished in what replaced the Aldon Sound, namely, the final Sixties pop-music trend (it leaked into the Seventies): the sound of the counterculture, hippies playing for hippies. Hendrix’s virtuosity, Lennon’s lyrical smarts, and the Band’s evocations of rural America now mattered (almost) as much as money. Of those lucky few survivors, the prime example was Carole King, who went from prolific cubicle occupant to early-Seventies Earth Mother, whose 1971 album Tapestry sold 30 million copies, making it one of the best-selling albums ever, whose title song, I’ll note, is one of the treacliest songs of its day, if not of all time.

Standing well behind King on the survivors’ line, but a hardy, resourceful survivor nonetheless, was Al Kooper. Al’s chops were nothing special, but he had a rarer gift, more or less unerring taste, which would stand him in good stead as an arranger and producer in years to come. Also to his credit, Kooper was, and remains, at 80, one of rock & roll’s great wise-guys, rarely at a loss for a smart-ass, if rarely mean-spirited, remark, and a comeback to your response. He does have the dubious distinction of discovering, and producing three albums on, Lynyrd Skynyrd.

An undeniable distinction, however, which Kooper alone can claim, is that he was the only neo-Tin Pan Alley survivor present, and not as a mere witness, but as a major contributor, at perhaps the most significant single event in the turning of the tide, ie. rock’s transition from dopey music for teens to a genre which, every now and then, could be expected to produce Art. The event in question was the Columbia Records session, on June 16th, 1965, at which Bob Dylan raised the bar for songwriters to yet-unequalled heights: Actual Literature at a Really High Volume.

The visionary record man John Hammond signed Bob Dylan to Columbia in 1961. Hammond’s stodgier colleagues referred as the new signee as “Hammond’s Folly,” especially after a first album that went nowhere. By Dylan’s fifth album, Bringing It All Back Home, released in March 1965, he was a superstar, working on the songs for his second great album of that year, Highway 61 Revisited.

“In 1965,” Al writes, “being invited to a Bob Dylan session was like getting backstage passes to the fourth day of creation. And make no mistake about it, a formal invitation was a prerequisite.” As it happened, the Columbia producer Tom Wilson had taken a shine to Al, and invited him to the second day, June 16, 1965, of a two-day session for Highway 61 Revisited. I’m going to turn the tale over to Kooper, as good a storyteller as any, (though he gets a few key facts wrong, chiefly, the day that Dylan & Co. cut the bard’s magnum opus.

June 16, 1965: Listening back to a take of “Like a Rolling Stone.” Among the gathered are: left, at desk and in sport jacket, producer Tom Wilson; rear, to Wilson’s right, Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman; Dylan, typically poker-faced; and slouched at right, rear, Al Kooper, who played the organ licks that almost immediately became iconic, though Kooper barely knew how to play the instrument and wasn’t supposed the leave the control room. On this day, chutzpah prevailed.

“Wilson felt comfortable enough to invite me to watch an electric Dylan session, because he knew I was a big Bob fan. He had no conception of my limitless ambition, however. There was no way in hell I was going to visit a Bob Dylan session and just sit there pretending to be some reporter for Sing Out! magazine! I was committed to play on it. I stayed up all night preceding the session, naively running down all seven of my guitar licks over and over again. Despite my noodling at the piano, I was primarily a guitar player at the time and having gotten a fair amount of session work under my belt, I had developed quite an inflated opinion of my dexterity on said instrument.

“The session was called for two o’clock the next afternoon at Columbia Studios, which were at 799 Seventh Avenue, between West 52nd and West 53rd Streets. Taking no chances, I arrived an hour early and well enough ahead of the crowd to establish my cover. I walked into the studio with my guitar case, unpacked, tuned up, plugged in, and sat there trying my hardest to look like I belonged. The other musicians booked on the session (all people I knew from other sessions around town) slowly filtered in and gave no indication that anything was amiss. For all they knew, I could have received the same call they’d gotten. Tom Wilson hadn’t arrived as yet, and he was the only one who could really blow the whistle on my little charade. I was prepared to tell him I had misunderstood him and thought he had asked me to play on the session. All bases covered. What balls!6

“Suddenly Dylan exploded through the doorway with this bizarre-looking guy carrying a Fender Telecaster [who] commenced to play some of the most incredible guitar I’d ever heard. And he was just warming up! That’s all the Seven Lick Kid had to hear; I was in over my head. I embarrassedly unplugged, packed up, went into the control room, and sat there pretending to be a reporter from Sing Out! magazine.

“Tom Wilson then made his entrance—too late, thank God, to catch my little act of bravado…. I asked Tom who the guitar player was. ‘Oh, some friend of Dylan’s from Chicago named Mike Bloomfield. I never heard him but Bloomfield says he can play the tunes, and Dylan says he’s the best.’

“The band quickly got down to business. They weren’t too far into this long song Dylan had written before it was decided that the organ player’s part would be better suited to piano. The sight of an empty seat in the studio stirred my juices once again; it didn’t matter that I knew next to nothing about playing the organ. Ninety percent ambition, remember? In a flash I was all over Tom Wilson, telling him that I had a great organ part for the song and please (oh God please) could I have a shot at it. ‘Hey,” he said,’ you don’t even play the organ.’

“‘Yeah, I do, and I got a good part to play in this song,’ I shot back, all the while racing my mind in overdrive to think of anything I could play at all. Already adept at wading through my bullshit, Tom said, ‘I don’t want to embarrass you, Al….” and he was then distracted by some other studio obligation. Claiming victory by virtue of not having received a direct ‘no,’ I walked into the studio and sat down at the organ.

“Me and the organ: It’s difficult to power up a Hammond organ. It takes three separate moves, I later learned. If the organist (Paul Griffin) hadn’t left the damn thing turned on, my career as an organ player would have ended right then and there. I figured out as best I could how to bluff my way through the song while the rest of the band rehearsed one little section. Then Wilson returned and said, ‘Man, what are you doin’ out there???’ All I could do was laugh nervously…. Wilson was a gentleman, however. He let it go.

“Imagine this: There is no music to read. The song is over five minutes long, the band is so loud that I can’t even hear the organ, and I’m not familiar with the instrument to begin with. But the tape is rolling, and that is Bob-fucking-Dylan over there singing, so this had better be me sitting here playing something. The best I could manage was to play hesitantly by sight, feeling my way through the changes like a little kid fumbling for the light switch. After six minutes they’d gotten the first complete take of the day and everyone adjourned to the control room to hear it played back.

“Thirty seconds into the second verse of the playback, Dylan motioned toward Tom Wilson. ‘Turn the organ up,’ he ordered. ‘Hey, man,’ Tom said, ‘that cat’s not an organ player.’ Thanks, Tom. But Dylan wasn’t buying it: ‘Hey, now don’t tell me who’s an organ player and who’s not. Just turn the organ up.’ He actually liked what he heard!

“If you listen to it today, you can hear how I waited until a chord was played by the rest of the band, before committing myself to play in the verses. I’m always an eighth note behind everyone else, making sure of the chord before touching the keys. Can you imagine if they had to have stopped the take because of me? At the conclusion of the playback, the entire booth applauded the soon-to-be-classic ‘Like a Rolling Stone,’ and Dylan acknowledged the tribute by turning his back and wandering into the studio for a go at another tune…. Later, as everyone was filing out, Dylan asked for my phone number—which was like Claudia Schiffer asking for the key to your hotel room…. Elated, I walked out into the street realizing that I had actually lived out my fantasy of the night before, although not quite exactly as I had planned it.”

I hesitated to include The Song—we’ve all heard it three million times. But focus in on how great that organ, played by a rank beginner, still sounds 60 years later.

What Kooper refers to as “my incompetent organ playing” quickly became, as he put it, “a publicly recognized trademark of the ‘new Dylan sound.’” Kooper underestimates his playing. Still only 21, he had developed substantial musicianship. Improvising licks that fit “Like a Rolling Stone” like a glove, and on an instrument he could barely play, was no small feat, in addition to its almost unbelievable chutzpah. Reluctantly leaving aside drummer Bobby Gregg’s opening snare-drum thwack and Paul Griffin’s superb piano playing, I’m going to venture that “Like a Rolling Stone” has three iconic components: 1) the lyrics’ unprecedented richness, the verbal virtuosity that Dylan increasingly had at his command; 2) that voice, as far from bel canto as a voice can get, but capable of infinite nuance; and 3) Al Kooper’s organ, especially the four-note lick7 that follows Dylan’s sneering “How does it feeeel.” Kooper’s playing gives the song its identity as forcefully as do Dylan’s lyrics and voice. Considering his inexperience with the Hammond B-3, the musical instincts that he brought to his performance are remarkable.8

“Like a Rolling Stone” rose to #2 that summer, wreaking bedlam among record-company and radio executives. As for Al, he was now an in-demand session player, especially on organ, which he was desperately trying to learn how to actually play (he would, as we know). He was an individual with éclat, who in rapid succession joined, and excelled in, two influential mid-to-late Sixties bands. These were the Blues Project, which, between 1965 and ‘67 could claim an avid following of teen cognoscenti, present company included; and Blood, Sweat and Tears, an adventurous experiment—a rock band with a sophisticated, jazz-trained horn section—that Kooper conceived, music-directed, sang on and played keyboards in, and from which he was unceremoniously dumped after just one album, Child is Father to the Man. The critic William Ruhlman called the record “Al Kooper’s finest work…. This is one of the great albums of the eclectic post-Sgt. Pepper era of the late ‘60s…. the sound of a group of virtuosos enjoying [themselves] in the newly open possibilities of pop music.”

Kooper unbound, but only momentarily. The founder, music director, co-arranger, organist, pianist, and lead vocalist for Blood, Sweat and Tears, whose first album, “Child is Father to the Man,” was Kooper’s finest achievement. Almost immediately after its release, Kooper was fired from the band. This song, “So Much Love,” was written, in their Aldon Music days, by Carole King and Gerry Goffin, stars of the early-Sixties songwriters’ community in which Kooper was just a peon. (Kooper, btw, is the central figure in the album-jacket photo; the munchkin on his lap is the one in white pants and sox).

So here is where we take leave of Al Kooper, midcareer (though I consider his essential work, in the Blues Project and Blood, Sweat and Tears, behind him). Kooper was there in the late Fifties, when Neo-Tin Pan Alley was born, and he was there, unbidden, at the momentous event that triggered the genre’s downfall and gave birth to its successor, the sound of Hendrix and Cream et al. Al Kooper was there, period; he should have been inducted years ago into the dubious institution that denied him entry for years and finally admitted him in 2023, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

The Tin Pan Alley of the Thirties and Forties, Yip Harburg’s and Johnny Mercer’s territory, was, in fact, Tin Pan Alley’s second iteration. The original Tin Pan Alley, centered around West 28th Street, between Broadway and Sixth Avenue, flourished between the 1890s and late Twenties. Here is where the Russian immigrant Irving Berlin had his first successes, the home, too, of George M. Cohan, the young George Gershwin, and other pioneers of American pop.

Speaking of chord changes: from time to time, Kooper and I refer to the 1-IV-V progression. This is the standard blues progression of the blues, present as well in a huge number of rock, rhythm and blues, and country songs If a 1-IV-song is in the key of G, the “1” is G, the “IV” is C, four notes above G, and the “V” is D, five notes above G. There are literally thousands, probably tens of thousands, of 1-IV-V songs.

For an extended profile of Griffin, see my November 25, 2023 post, “The Lonesome Tale of Paul Griffin.”

As with Griffin, I’ve written a detailed biographical essay on George Goldner: “George Goldner, Record Man: Winning Big, Losing Bigger,” posted on December 7, 2023

The four-day session would not have been merely for one song. These must have been the sessions for B.B. King’s 1969 album Completely Well, which featured “The Thrill is Gone,” with which King emphatically crossed over from the R&B to the pop charts.

to the extent that it has one, the world’s conception of Kooper, to which he has never objected, is, as I’ve indicated, as an incurable wise-ass. This is at striking odds with Suze Rotolo’s portrayal of Al in her memoir, A Freewheelin’ Time (see my post of January 11, 2024, “John Lee Hooker, Suze Rotolo & Others). Rotolo was Bob Dylan’s girlfriend from 1961 to 1964. By ‘65, they were no longer an item, but continued to see each other. “Sometimes we just enjoyed each other’s company,” Rotolo writes. No doubt at Dylan’s request, his manager, Albert Grossman, invited Suze to one of the sessions for Dylan’s album Highway 61 Revisited. Rotolo’s Kooper is an entirely appealing fellow, relaxed, busy and evidently quite at home with Dylan, Grossman, the guitarist Mike Bloomfield, and the session’s other stellar participants. Kooper was, in fact, a nervous wreck, engaged in pulling off a brazen stunt that could have gotten him bounced from the session, from all future Columbia Records sessions, and possibly, once word got out, from rock music itself. There’s a cognitive disconnect here, between Suze’s and Al’s accounts. Here’s Suze: “What struck me about Al Kooper the first time I met him was his lust for life. Everyone was young and energetic—it comes with the territory—but Al took it up a notch. If I ran into him on the street, in a record store—anywhere—and he was excited about something, his enthusiasm was catching. Al was tall, wiry, and always full of droll tales and shaggy-dog stories. He was a really funny guy and a very serious musician. During the [Highway 61] session, Al was the liveliest thing in the room, popping up all over the place like a jack-in-the-box. He scooted around doing several things at once.”

Dylan recorded “Like a Rolling Stone” in C; the four notes in question are C-A-G-A-G.

Elsewhere, Kooper points out that he did have some experience playing organ. “I just didn’t know too much about what made it work,” he told me, ie. which knobs to twist, buttons to push; how to obtain effects, how to operate the pedals, etc.

A note on the audio interview, edited down from a much longer,more rambling conversation. It appears here in two segments spliced together. The first ends at 9:43.

Rather than proceed in precise chronological order, Al and I moved freely from one aspect of his Neo-Tin Pan Alley environment to another: the major songwriters (Carole King, Burt Bacharach); the music publishers (who essentially controlled everything); the top session musicians; the protagonist, arriving on the scene as a 14-year guitar player and novice songwriter, and the legendary, if rarely described, event in which Al played a key role and which ended the era of rock & roll as simple-minded music for kids: the 1965 session, that is, at which Bob Dylan, with Al Kooper’s help, recorded his magnum opus, “Like a Rolling Stone.” Enjoy the listen; you’re likely to learn some stuff worth knowing.

Wonderful piece, I've also heard the story many times and there were some great new details provided here. However, I can't help quibbling with this: "He does have the dubious distinction of discovering, and producing three albums on, Lynyrd Skynyrd" - why dubious? Lynyrd Skynyrd was a legit and musically accomplished band, paying dues in clubs and roadhouses for years before Al Kooper 'discovered' and produced them, and I submit that they transcended their political ambiguities by the time of the tragic plane crash. You don't have to love them, but give 'em their due in rock history, and acknowledge that songs like the anti-gun "Saturday Night Special" and their friendly back & forth with Neil Young over "Sweet Home Alabama" showed them to be more nuanced as artists than simply another 'redneck Southern rock band'.

I've heard that Dylan session story so many times--mostly from Al Kooper in documentaries--and I still love hearing it.