A 14-Year Wait for a Downer of an Album

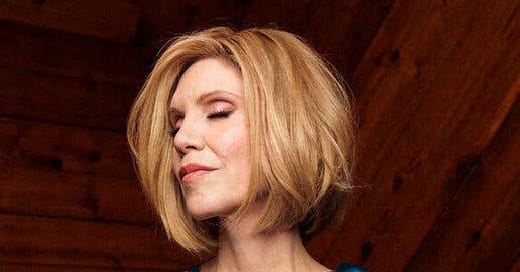

Alison Krauss and Union Station's first album since 2011 glows with virtuosity. But as with Krauss herself, a strain of darkness runs through it.

Arcadia, in Greek mythology and everyday modern usage, is a realm of peace and serenity, an idyllic domain. Why, I’d like to know, has Alison Krauss chosen the word as the title for an album many, if not most, of whose songs are about depression, death, and life’s bitter disappointments?1

To nobody’s surprise, “Arcadia”, Alison Krauss and Union Station’s eighth album and first in 14 years, entered “Billboard”’s Bluegrass Albums chart at #1.

Krauss, 53, is one of American popular music’s great vocalists: one of the only, if not the only, bluegrass, or bluegrass-rooted, musicians to achieve the kind of superstar status that transcends genre, winning 28 Grammys—that’s twice as many as Taylor Swift—and selling more than 12 million albums. to nobody’s surprise, Arcadia, the eighth album by Alison Krauss and the durable sextet Union Station, entered Billboard’s bluegrass chart this week at #1.

Krauss insists that the members of Union Station, which she has led since 1989 (when she was all of 18) are her full collaborators. This is not the case. With her pure, melting soprano, mastery of the fiddle, palpable onstage charisma, and savvy as a producer, Krauss calls the shots. Despite the presence in the band of masters such as Jerry Douglas, bluegrass’s top dobro player and an in-demand producer in his own right, Krauss has always been the main draw. 2

I’ve written about Alison Krauss before, a long time ago, in The New York Times of April 24, 1994, in what was probably (not to toot my own horn) the first portrait of the artist in a publication of national scope. Signed to plucky little Rounder Records, the champion of American roots music, Krauss at 22 was the object of a bidding war between almost every major label’s country-music branch (and more than one label’s pop division). Record executives coveted her with an almost voluptuous passion. “Next to my wife, and a few early girlfriends, I have never pursued a woman harder than I have Alison Krauss,” Kyle Lehning, then president of Asylum Records’ Nashville branch, told me. She turned them all down, preferring the artistic freedom that Rounder gave her. In 2017, concerned that the label, now part of a conglomerate, might stray from its roots-music values, Rounder’s three founders started Down the Road Records. Krauss went with them, the elephant in the room.

“Looks Like the End of the Road,” which opens Arcadia, establishes the album’s somber mood with lyrics like “I've run out of luck/Goodbye to the world that I know/Looks like the end of the road.”

When Union Station released Arcadia in March 2025, they hadn’t put out an album since 2011’s Paper Airplane, which went all the way to #3 on Billboard’s Top 200, a megahit by a megastar and her gang. Krauss has always been involved in outside projects: five solo albums, a number of collaborations, including her two double-platinum-selling collaborations with Led Zeppelin’s onetime frontman, Robert Plant, and more than a half-dozen movie soundtracks, most notably for the Coen Brothers’ O Brother Where Art Thou, with won the Grammy for Best Album in 2002 and has sold more than eight million copies. Another reason for Union Station’s long layoff was the dysphonia that Krauss developed in 2013. A vocal condition whose symptoms range from hoarseness to a total inability to use one’s voice, dysphonia had also afflicted one of Krauss’s heroes, the late guitarist/singer Tony Rice. Rice never regained his voice. Krauss was more fortunate. She was able to return to, and complete, the 2017 solo album, Windy City, which she’d been working on when her voice failed her.3

Somberer still: “Richmond on the James,” a Civil War ballad brought to Krauss’s attention by a musician/musicologist friend. The battle over, a mortally wounded soldier bids farewell to another, his best boyhood friend.

The other Union Station members also stayed active. Jerry Douglas is in permanent demand as a session player and is also one of bluegrass’s busiest producers; multi-instrumentalist Ron Block and bassist Barry Bales are busy session musicians as well. Dan Tyminski, the band’s lead guitarist and, until Arcadia, its part-time lead vocalist, has had a solo career for more than 20 years. “Everybody’s always gone and done their own thing outside of the band,” Krauss said recently. “When we come back together, it just makes the band stronger.”4

Back to Arcadia, the majority of whose songs bely its buoyant title. Like many songs written during the Covid pandemic, the opener, “Looks Like the End of the Road,” is grim. Written by singer/songwriter Jeremy Lister, it’s “a bitterly mournful waltz about disillusionment and despair,” wrote The New York Times’s Jon Pareles, “[that] sets the dark tone for Arcadia. All but two of Arcadia’s 10 tracks, Pareles pointed out, are in minor keys, “with lyrics full of bleak tidings.”

Lister also contributed the album’s closer, “There’s a Light Up Ahead,” which for Pareles “offers a glimpse of redemption,” a very quick glimpse. “The leafless limbs are shaped like veins against the sky,” sings Krauss, “and tears are falling down from tired and bloodshot eyes.”

Although not many journalists have noticed, Krauss has always been somewhat depressive. While a portion of Union Station’s songs are upbeat—their show-stopping version of Bad Company’s “Oh, Atlanta,” for instance (if it’s still in the repertoire)—the majority are not. Covering a Union Station concert in 2011, the New York Times’s Jon Caramanica wrote of Krauss that “sadness and tragedy are her milieus. The more abject the songs, like [the bereft] “Ghost in This House,” the more riveting she was.”

Two of Arcadia’s songs, "Richmond on the James” and “Granite Mills,” which burrow deep into the past, are filled with sorrow and, in “Granite Mills”’s case, with horror. In "Richmond on the James”, a dying Confederate soldier asks his comrade to “[take] a brown lock from my forehead/To my mother who still dreams/Of the safe return of her soldier boy/From Richmond on the James." “Granite Mills” is about an 1874 fire in a textile mill in Fall River, Massachusetts, in which 23 workers died, most of them children.5

The tragic narrative “Granite Mills,” its roots in a 19th-century textile mill fire, puts one in mind of two of Woody Guthrie’s greatest songs, “1913 Massacre” and “Ludlow Massacre.” That’s Russell Moore, new to Union Station, on vocals (see footnote #3).

Krauss isn’t especially clear about her need to visit some of the past’s darker episodes. “It’s that old idea of ‘In the good old days, when times were bad,’” she recently told a journalist from the website Country Standard Time. “Someone asked me, ‘How do you sing these tragic tunes?’ I have to. It’s a calling.” She considers it her job to sing songs like “Richmond on the James” and “Granite Mills,” as well as Arcadia’s second song, “The Hangman,” which is based on a little-known 1951 poem of that title that has been interpreted by some as a parable about the Holocaust. Coming across “The Hangman” several years ago, Krauss asked her brother, the bassist Viktor Krauss, to set it to music.

Back in 2002, Krauss, in a New York Times article titled “O Superstar, Where Art Thou?” (a more apt title would have been, “O Superstar, Who Art Thou?”), Daniel Menaker visited Krauss at the Nashville home she shared with her then-two-year-old son. Krauss and her husband of four years, Nashville musician Patrick Bergeson, divorced in 2001; Krauss has never remarried.

Near the end of his article, Menaker characterized his interview subject as someone with “an attraction to mischief and even darkness, mixed with fearfulness.” Menaker got it right. As Arcadia abundantly indicates, Alison Krauss is an individual who, even after thirty-plus years in the public eye, remains an enigma, whose inner world contains its share, and perhaps more, of dark corners.

Intriguing and useful comment from a reader re the new album’s title. I had no idea. He writes, “Lovely helpful writeup. One small thing: as a word and…place, ‘Arcadia’ has always coded for darkness, thanks to an old Latin phrase in which Death says “I too am in Arcadia” (ie even in Paradise everybody dies)…..Tom Stoppard had this in mind when he titled his gorgeous tragedy/comedy Arcadia. I think AK may have it in mind too—given the darkness you describe so beautifully.” Thanks for the insight!

Re this paragraph’s first sentence: I hesitate to call Krauss a bluegrass musician pure and simple, though it’s where she began. Not only does Union Station’s music often fall outside of bluegrass’s purview, but Krauss’s solo work, as we’ve seen, ranges widely indeed. I’m more comfortable calling Krauss and Union Station’s music “Americana.”

Windy City strays far from bluegrass. Produced by Buddy Cannon, a veteran of mainstream country, it consists of covers of easy-listening “countrypolitan” hits by the likes of Eddy Arnold, the Oak Ridge Boys, and Roger Miller.

During the Arcadia sessions, Tyminski announced his plans to leave Union Station when the album was done and pursue a solo career. Tyminski doesn’t sing on Arcadia, although he plays guitar and mandolin. Another prominent bluegrass singer/guitarist, the band IIIrd Tyme Out’s Russell Moore, sings Arcadia’s male lead vocals, and will add his voice and guitar to Union Station through the Arcadia tour. Tyminski, who joined Union Station in 1992, is the first member to depart since mandolinist Adam Steffey left in 1998 (and Steffey is back, part-time, playing on two tracks on Arcadia).

The release of Arcadia has sparked a one-man controversy over the origins of “Granite Mills.” According to musician/musicologist Tim Eriksen, who leads the folk/punk band Cornelia’s Dad (which recorded “Granite Mills” on its 1998 album Spine), “Granite Mills” and “Richmond on the James” “are two songs I gave Alison over the years.” Eriksen claims to have written both words and music to “Granite Mills. “I wrote the music about thirty years ago,” he said in mid-March of this year, “with lyrics I arranged from a Fall River newspaper poem that had some life as a song in that neck of the woods.” Eriksen doesn’t provide any information about the newspaper or the poem. Several newspapers covered the fire at the time; none were based in Fall River or were any closer to it than Boston, fifty miles away. What was the song from Fall River’s “neck of the woods” that Eriksen claims as the source of his lyrics? If he wants to claim authorship of “Granite Mills”’s lyrics, Eriksen is going to have to be a bit more precise about their origins.

Regarding “Richmond on the James”’s authorship, Eriksen has no problem acknowledging that the song is in the public domain, and lists a number of singers, from East Jaffrey, New Hampshire to Gloucester, England, from whom he has gathered the song. Arcadia’s Wikipedia page gives two people credit for words and music: Alison Krauss and a G.T. Burgess. The second author, nowhere mentioned by Eriksen, is of real interest—after much online searching, I found a poem titled “Richmond on the James,” credited to G.T. Burgess. (I could find no information about the fellow). The poem appeared in The Southern Soldier's Prize Songster, published by W. F. Wisely of Mobile, Alabama in 1864.

Eriksen clearly gave the song to Krauss; a version that he sings on his website is almost identical to Krauss’s, though it adds a sixth verse to Krauss’s five. Burgess’s poem resembles Krauss/Eriksen’s, but only to an extent: it has 10 verses to Krauss’s five and Eriksen’s six. So there you have it: 1) an ostensibly anonymous song (“Richmond on the James”) which turns out to have an actual author; and 2) “Granite Mills,” which Dr. Eriksen (he has a Ph.D in ethnomusicology) claims, not very convincingly, to have written. As Bob Dylan once said, “Folk music is the only music where it isn’t simple.”

Mark Twain supposedly once said that Mahler's music was better than it sounded. Maybe Allison Krausse's music is actually more positive than it sounds.

I enjoyed it…………it expresses what it expresses. pretty authentic.