RY COODER IN FOUR EPISODES, 1985-2023, EPISODE 4: Closing the Circle

"Joachim said, 'What are you going to do with Taj Mahal?' I said, 'I don't have the faintest idea.' And he said, 'Well, you better do something, because it's a good idea that'll intrigue people.'"

“CLOSING THE CIRCLE,” THE FIFTH AND FINAL EPISODE of this series, is based in part on the most recent of the many conversations that Ry Cooder and I have had over the years. You can listen in on it below. We spoke on March 22nd, 2022, on the eve of an auspicious occasion: Cooder’s first recording session in 55 years with the indomitable Henry St. Claire Fredericks, Jr., better known as Taj Mahal.

Cooder and Taj (whom nobody calls Mahal) first crossed paths at Los Angeles’s Ash Grove club, the hub of the small but hopping L.A. folk scene of the early-to-mid-‘60s. In the summer of 1965, Bob Dylan plugged in, the Byrds’ cover of Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man” soared to No. 1, and folk-rock music was in the air. “Everyone was looking for the next Byrds,” Cooder says. “It was Rocket to Stardom. So Taj and I formed a band, because that’s what you did.” Except that the Rising Sons, as Cooder, 17; Taj, 23, and their bandmates named themselves, were unerringly off-target: a blues-rock band in the heyday of folk-rock.

“All we wanted was to play some blues with rhythm,” Cooder says. “Which wasn’t what the record company was interested in, at all. So the whole thing fizzled out, and that’s the long and the short of the Rising Sons.” Some of the band’s music was first-rate electric blues; the rest was pretty sterile pop-rock. Columbia released a Rising Sons single, which went nowhere, and the label dropped the group but kept Taj on hand. “He was a character that they could present,” Cooder recalls. “He wasn’t a ghetto guy, by any means; he had a rapport with young white people. Somebody at Columbia saw that and said, ‘We can do something here,’ and they kept him, and he did alright for himself.”

Sure enough, in 1968 came Taj Mahal’s eponymous solo debut, a bracing, infectiously high-spirited album whose timing was just right. On the heels of folk-rock came a new vogue, the blues-rock of Paul Butterfield, Canned Heat, the Electric Flag. The public, moreover, was ready for a young, Black (read: “authentic”) blues singer fronting a rock band. Taj sang, played harmonica and guitar, and Cooder played guitar and mandolin. It was a hell of a record. Ry Cooder and Taj Mahal never recorded together again.

Or not for a really long time.

In 2014, they shared the stage at the Americana Music awards show, playing “Statesboro Blues,” which they’d recorded both as Rising Sons and on the first Taj album, and the years fell away. “It felt really good,” Cooder says. Cooder’s son and percussionist, Joachim, who is media-savvy where Ry is media-averse, was convinced that people would be intrigued by the old guys’ backstory, by the Return of the Rising Sons. “Wait a minute, this is kind of interesting,” Ry remembers thinking “while I was watering my yard, which is mostly what I do now.” Taj was game, and in June, 2021, a half-century-plus after their first sessions together, the pair reconvened at Joachim’s house in Altadena, Ca., just north of L.A. (Cooder had recently moved two blocks away.) Cooder was intent on recording in Joachim’s living room, which he says, “has a quality most recording studios don’t have, which is that it makes you sound better than you do. I don’t want to see a record studio again, ever, I swear to God. You want something that can be easy and fun and ambient.”

They recorded for three days, with Joachim on drums and bass, and the result was Get on Board: The Songs of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, inspired by the 1953 album of the same title by two masters of the Piedmont blues style. Sonny and Brownie were heroes of the 1940s and ‘50s folk revival, the era of Guthrie, Seeger, and the Almanac Singers. They were heroes to Cooder, too, who’d discovered the original Get on Board in 1959, when he was 12, as well as to Taj, who first heard Sonny and Brownie circa 1960 as an agriculture major at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Sonny Terry played harmonica, as does Taj on the new album. Brownie McGhee played acoustic guitar; here, Cooder plays acoustic and electric guitars, plus mandolin. (1) Joachim played drums and bass. The album won Cooder his seventh Grammy and Taj his fourth. Is another collaboration in the works? Ry is 76, Taj, 81. But never say never.

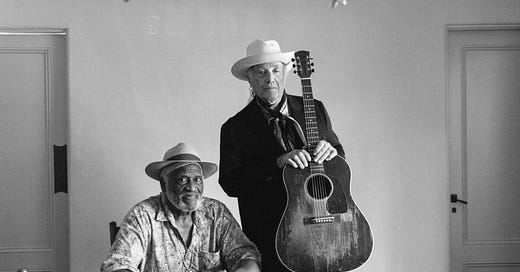

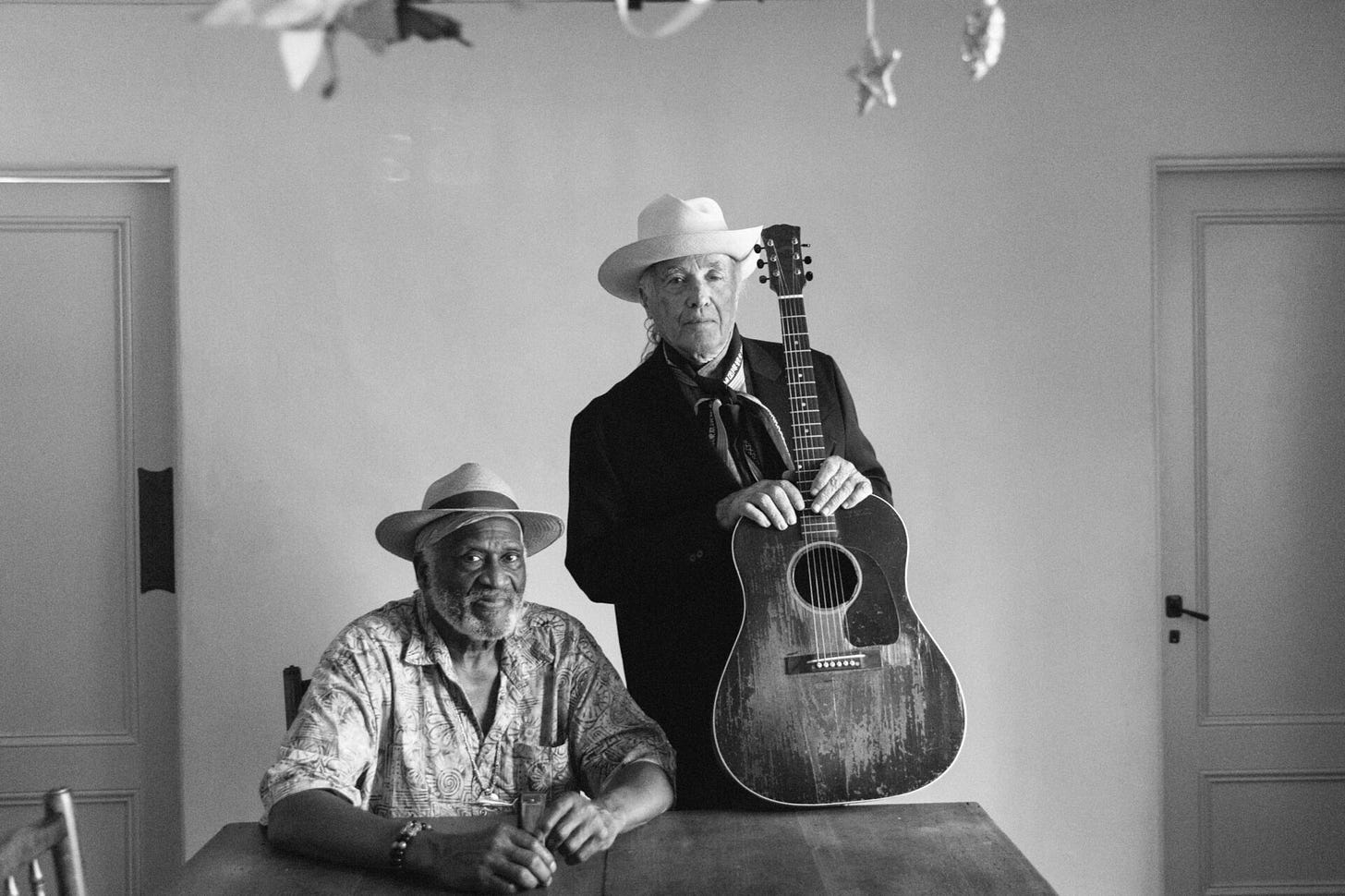

(Above) Two compañeros reunited, Taj Mahal (left) and Ry Cooder (right) in June, 2021, when they recorded their Grammy-winning reunion album, Get On Board: The Songs of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.

(Below) “I play better now, that's about the size of it”: Cooder on his two snarling electric slide-guitar solos on “My Baby Done Changed the Lock on My Door,” Get On Board’s bracing opener.

(Above) The Turtles? The Buckinghams? No, The Rising Sons, the short-lived 1965/’66 band that featured Ry Cooder, 18 (far right) and Henry St. Claire Fredericks, aka Taj Mahal, 23 (second from right). Apart from the band’s general mediocrity, there was no audience for them; attempting blues-rock in the folk-rock era, they flopped.

(Below) By 1968, the public was ready for blues-rock, and for Taj Mahal’s memorable debut album, with “Ryland P. Cooder,” as per the liner notes, on board. Here is the closing song, Taj’s take on the Robert Johnson classic “Walkin’ Blues,” featuring Ryland P.’s virtuosic mandolin, recorded when he was all of 20.

Early last spring, I conducted separate interviews with Cooder and Taj for a Tidal Magazine article, “Old Blues Was Us.” (You’ll hear Taj hold forth elsewhere, in due time.) At 76, Cooder was exactly twice as old as when I’d first interviewed him. That would have been in July 1985—see Episode 1. The Cooder of ‘85 was a tough interview, a testy individual from whom one had to pry answers and who did not suffer fools gladly. He was mellower now, a relaxed, engaged conversationalist, a pleasure to do business with.

Cooder plays mandolin, for instance, on “Hooray, Hooray,” bearing down especially hard. “I always play the mandolin that way,” Cooder says. “I played the way I play when I go to play this music, which is to say that I stomped as hard as I fucking can. Incidentally, it didn’t even occur to me that I had played the same mandolin, an F-4 Gibson, on Taj’s first album. Taj remembered. He's got an amazing memory, he remembers all kinds of crazy shit.”

Envoi

WHEN RY COODER’S COLLEAGUE, FRIEND, and fellow stringed-instrument master David Lindley died in March 2023, I wrote a brief tribute in the June issue of Stereophile magazine. It ended thus:

“Today, when fewer and fewer musicians play actual instruments, musicians like Lindley are receding into the past, along with an immeasurably old and rich tradition whose diminution began in the middle of the 20th century: the practice of making music by hand, in real time. Nothing will replace the sounds that Lindley made every day of his life, and that Ry Cooder, 76, or Taj Mahal, 81, continue to make: the sound of fingernails, or a pick, or flesh, on wound-metal strings.”

I sent the Lindley story to Cooder, who emailed back right away: “Very good job, especially the windup. ‘Receding into the past’—that sure is a fact.”

“The sound of fingernails on wound-metal strings.” Blind Blake’s 1929 “Police Dog Blues,” interpreted by Ry Cooder, 23, on his 1970 debut album.

Here’s our freewheeling interview, recorded while Cooder was watering his yard, one of his favorite current pastimes.