Robbie Robertson: A Hawk Flies South, Chapter 3 of 4, "The Code of the Road"

One of rock's iconic figures tells the story of how a 1950s Toronto street punk turned himself into a master. "The Code of the Road" is Chapter Three of four.

Robbie made it through his probation period without a hitch, a full-fledged Hawk now, making $135 a week. Not that Ronnie Hawkins let him forget for a minute that he was still a wet-behind-the-ears 16-year-old with a lot to prove.

“Nobody ever worked harder than I did,” Robbie says. “All I did was practice. Everywhere, all the time.” He did his best, too, to adopt both Hawkins’s swagger and Levon’s down-home ease. “I was trying my hardest to fit in. I didn’t want anyone to all of a sudden say, ‘Where did he come from?’ If Ronnie or Levon had said, ‘Around here we eat chickens’ heads and fuck pigs,’ I’d have said, ‘Order ‘em up!’

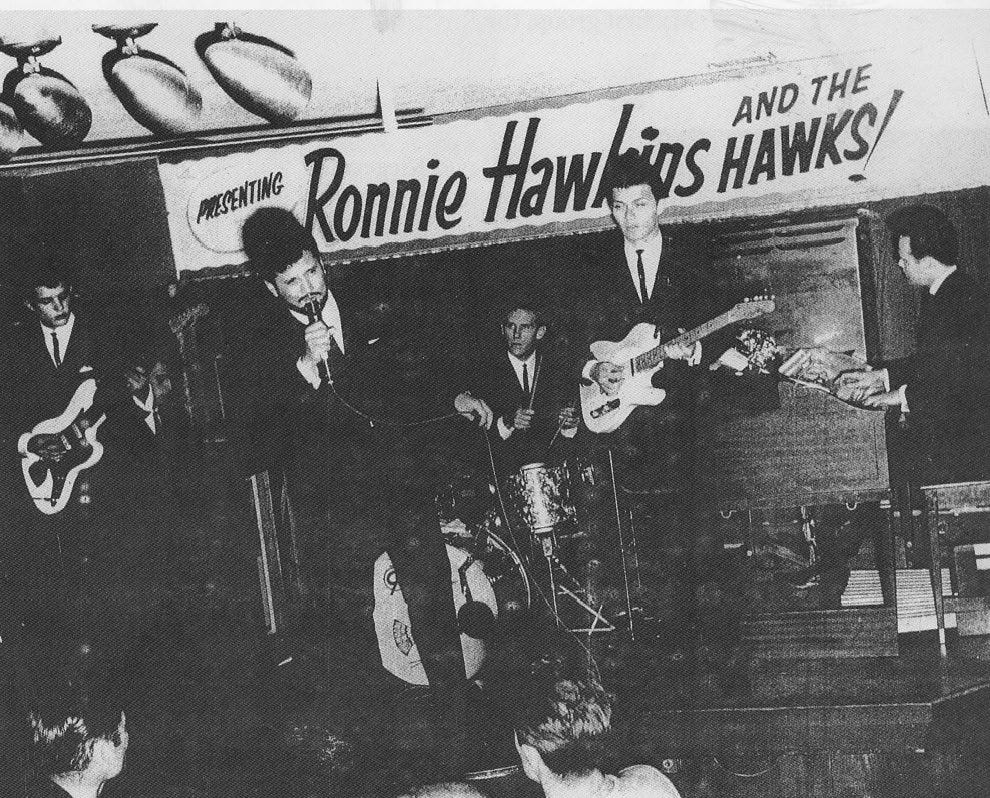

Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks’ final lineup, ca. 1963. Five years later, the Hawks were the Band. From left: Rick Danko, bass; largely hidden behind Danko: Richard Manuel, piano; Hawkins; Levon Helm, drums; Robbie Robertson, guitar; Garth Hudson, organ

After two or three years of thinking about nothing but guitar, “I began to experience this feeling of emptiness,” Robbie says. “I thought, ‘There’s something missing.’ What it was, I realized, was knowledge. At eighteen, nineteen, twenty years old, I became a book junkie,” spending his free time combing bookstore shelves with the same assiduity he applied to his playing. Given the Southern scenery that Robbie largely passed through, it isn’t surprising that his favorites were Faulkner, Eudora Welty, and Flannery O’Connor, although he also loved Steinbeck.

Ronnie Hawkins hated Robbie’s newfound lust for literature. “He could see this kind of sophistication coming over me. I had a bigger vocabulary and I would talk about things Ronnie had no use for. Especially anything in the least bit mystical. I remember one day, I thought he was going to fire me. I was reading The Way of Zen, by Alan Watts. Ronnie saw it and he wanted to puke. ‘Fucking ways of motherfucking Zen. In my goddamn band. Shit, son.’ He was just disappointed.”

By 1964, the Hawks were beginning to chafe under Ronnie’s rules of order. Hawkins, moreover, was often not turning up for gigs, attending to other business and leaving the Hawks to entertain on their own, ie. work harder for no extra pay.

It was time to split, and they did, settling on a name: Levon and the Hawks. They hired a booking agent and didn’t do at all badly, expanding their circuit beyond Hawkins’s established venues to include prestigious clubs like Manhattan’s Peppermint Lounge. Mistake. The Peppermint Lounge was the center of the Twist craze, and the Hawks insisted on playing untwistable music, ie. slow shuffles along the lines of their idol Muddy Waters’s “Mannish Boy.” As Robbie says in Testimony, “One of the owners flipped out and pulled Levon aside.”

“‘What is this shit you’re playing?’

“‘We’re playing good music, sir. That’s what we do,’ Levon answered.

“‘You don’t do more Twist music, we’re going to fire you.’

“‘Fine with me,” said Levon, “I can’t wait to get out of this piss-ass joint.’”

But all the while, the Hawks were broadening their circle of musician and music-biz friends. Playing Toronto’s Concord Tavern, they met the rising young blues singer John Hammond, who sat in. Normally, Hammond performed solo, but playing with a band, especially one this good, blew his mind. “John was ecstatic,” Robbie writes in Testimony, “and said he wanted this electric experience to be his next record.” True to his word, Hammond hired Robbie, Levon, and Garth to play on his 1965 album So Many Roads. On this album’s version of Bo Diddley’s “You Can’t Judge a Book By the Cover” Robbie plays the best solo, or the best on record, of his early years, the aggressive, virtuosic chops he’d perfected as a Hawk on full display. Robertson would eventually, and selflessly, trade his guitarslinger’s fury for the spare, ensemble-oriented style of his Band years.

John Hammond’s take on Bo Diddley’s “You Can’t Judge a Book By the Cover,” distinguished less by Hammond’s mimicry of rural black vocal styles—it wouldn’t wash today—than by perhaps Robbie’s greatest early solo. Robbie, Levon and Garth are listed on the credits as “Jaime R. Robertson,” “Mark Levon Helm,” and “Eric Garth Hudson” on organ. Also on hand were Charlie Musselwhite (harmonica) and Mike Bloomfield, playing piano, not his usual guitar. Hammond thought the world of Robbie’s playing (see footnote 2, below), and evidently asked Bloomfield, a great blues player, to step aside for the visiting Hawk.

[Note: footnote #3 has its own, 1:21 audio segment]

1) “I remember this Indian kid…” (spoken by Robbie at start of the first audio segment): In 1961, Robbie encountered a young, appealingly unassuming guitar player at the Cimarron Ballroom in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The kid, whom Ronnie Hawkins apparently knew—he called him “Indian Ed”—offered to carry Robbie’s gear after the show. Although he was only slightly younger than Robertson, Jesse Edwin Davis III had little to none of Robbie’s experience. In time, Jesse Ed, as he came to be known among his fellow musicians, turned into an exceptional guitarist, one of rock & roll’s best. He was admired especially for his work on Taj Mahal’s first four albums (note especially Davis’s playing, on guitar and piano, on the songs “Six Days on the Road” and “Keep Your Hands Off Her,” from Taj’s 1969 double album Giant Step/De Ole Folks at Home). Davis had a spare, economical style, much like Robertson’s during Robbie’s later, Band years, often choosing to play one note where others would have played an attention-grabbing cluster. Davis shone on many artists’ albums: Jackson Browne’s 1972 debut, for instance, on whose “Doctor My Eyes” Davis lets fly a memorable solo.

Jesse Ed was of Comanche, Muscogee, and Seminole ancestry, an enrolled member of the Kiowa Indian Tribe of Oklahoma. His father, Jesse Edwin Davis II, was a prominent artist whose nome d’arte was Asawoya, or Running Wolf.

Davis struggled with drug and alcohol addiction for years. Late in life he worked as a substance abuse counselor, but could not overcome his own addictions. He died on June 22, 1988 in Los Angeles, of an apparent overdose.

2) In the matter of Robbie Robertson, John Hammond, and Roy Buchanan. The last, a brilliant guitarist “with more tricks up his sleeve than Houdini,” in Robbie’s words, put in several brief stints as a Hawk. In 1960, nervous about Robertson’s youth and rawness, Ronnie Hawkins gave Buchanan a tryout. Buchanan turned out to be more than slightly eccentric. When Robbie, for instance, asked him where he’d acquired his skill, Buchanan replied that he was half-wolf. “That shit’s too damn weird for me,” said Hawkins, and Buchanan was given his walking papers. He returned, briefly, a few years later, when Robbie—by his own lights—bested Buchanan in a toe-to-toe guitar duel.

A troubled soul, Buchanan was incapable of steady employment, a longtime drug and alcohol abuser whose 1988 death was ruled a suicide. Yet he had, and has, a rare renown as one of roots music’s incomparable guitarists. Two of Buchanan’s albums, one early and one late—his eponymous 1972 debut and 1985’s When a Guitar Plays the Blues—are especially satisfying. The common wisdom, however, is that Buchanan was at his best in live performance. I never had the good fortune to hear him in the Washington, D.C.-area dives he frequented.

John Hammond was familiar with both Robbie’s and Buchanan’s work. When I interviewed Hammond in 1991, he insisted that between the Robertson who played on Hammond’s So Many Roads and Buchanan, Robbie was the more accomplished player: high praise.

3). When Levon and the Hawks left Ronnie Hawkins, it was only natural that Robertson devote increasing time and energy to developing the songwriting gift that had lain largely dormant during Robbie’s Hawkins years. Within a few years, which included prolonged exposure to Bob Dylan, Robertson emerged as an accomplished writer. Like many songwriters—Dylan is the most outlandish example—Robbie preferred to clothe the act of songwriting in an air of mystery. It wasn’t inarticulateness that led Robbie to say, discussing how he came to write one of his earliest and greatest songs, “The Weight,” that “basically, it was all I could think of at the time.” It was a good songwriter’s reluctance to hand listeners a convenient précis, to break down into a batch of ingredients something that is, at its best, a small miracle, the interaction of skill and chance to produce something new under the sun.

On the other hand, Robbie, again like many a songwriter, was all too quick to express disdain for research. There was nothing shameful about visiting the Woodstock, NY library to bone up on the last days of the Confederacy; it was spadework like this that gives another of Robertson’s finest songs, “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” its heft of authenticity. Perhaps the song’s richest, most reality-studded lines is its terse opening couplet, a reference to the Union General George Stoneman’s destruction of the Confederacy’s Danville, Va. railroad: “Virgil Caine is my name and I served on the Danville train/Til Stoneman’s cavalry came and tore up the tracks again….” Yet in our interview, Robbie denied his library visits (which he would mention in Testimony). “I’d already read all that stuff,” he told me, “and just kind of remembered what I could remember and that’s what I used.” Again, you need not be abashed about doing your homework. Poetry needs facts on which to drape itself. On the other hand, Robbie’s response, when I asked him how Virgil Caine, “Dixie”’s stoically mournful narrator, came to him, struck me as candidly truthful. “I don’t know,” he said. Great songwriting may need facts for ballast, but at bottom it works in wondrous ways.