PAUL SIMON ON ALMOST EVERYTHING: Introduction and Chapter 1 of 5, "Pounding Pavement, Paying Dues: 1941-1960"

As his friend the actor Elliott Gould once said, “He’s a hard-nosed little guy who refuses to be beaten.”

Introduction

January 1984 found Paul Simon reeling from two of the biggest flops of his career: the morose little 1980 movie One Trick Pony, which cost Warner Brothers $8 million and grossed a dismal $840,000, and his fourth solo album, 1983’s Hearts and Bones, which, at barely 400,000 copies sold, was easily his worst-selling solo record. In a cover story in Billboard’s first issue of ‘84, the nation’s leading radio programmers complained that their listeners wanted new acts, not middle-aged introverts whose best years were behind them. One went so far as to say, “We’re not going to play Paul Simon anymore.” Reading the piece, Simon thought, “Well, OK, they’re not going to play me anymore. So now what?”

Fast-forward to early 1986. Simon sat at a conference table surrounded by Warner Records executives, finally ready to give the suits a listen to his just-completed new album. Simon’s longtime engineer, co-producer, and comrade-in-arms Roy Halee remembered the meeting “as if it were yesterday. You’ve got to remember, Warners was hot with Prince and Madonna and Paul was coming off two disappointments. A lot of people in the room were probably wondering why they were wasting their time with another Paul Simon album. As the music started, I could see people looking at each other, going, ‘What the hell is this African stuff?’ There was a lot of shuffling in the room and people looking at their watches.” Lenny Waronker, Warner’s president, “sat there listening intently,” recalled Halee. “When it was over, Lenny got up said, ‘This is wonderful. This is great. This is exciting!’” Warner CEO Mo Ostin—long respected, as was Waronker, as the rare music-biz executive gifted not merely with business tsekel but with taste and intelligence—was equally thrilled. What happened next, recalled a disgusted Halee, “is so typical of how people at record companies react when their bosses get enthusiastic: people who had been scratching their heads started going over to Paul and patting him on the back.”

The record, of course, was Graceland, which went on to sell 16 million copies, win the 1987 Grammy for Album of the Year, and take its place as one of the greatest albums of the latter half of the 20th century. As Simon’s friend the actor Elliott Gould once said, “He’s a hard-nosed little guy who refuses to be beaten.” And one of a small handful of geniuses in 20th (and 21st)-century pop, an apparently inexhaustible producer of Grade-A music.

In August 1993, over the course of some 10 days, I conducted six hours’ worth of interviews with Simon for a profile that ran in that November’s Life magazine. We spoke in Simon’s office in legendary 1619 Broadway, the Brill Building, in what had once been Manhattan’s bustling music district, and on the phone, Simon from the house in Montauk, Long Island that he shared with his third wife, the singer Edie Brickell. The pegs for my story were two: Warner Records’ release of a three-disc set, Paul Simon, 1964-1993, and a series of 21 globe-spanning concerts that reunited Simon with four decades of collaborators, from Art Garfunkel to the South African a capella vocal group Ladysmith Black Mambazo.

Paul Simon on Almost Everything, the five-chapter series I’m just completing, contains substantial audio segments of our ‘93 interviews, accompanied by in-depth, freshly written text, photographs, and some of Simon’s best music, including lesser-known gems. Four chapters have already been published on my Substack, tonyscherman.substack.com. Chapter 1 explores Simon’s 1950s apprenticeship writing “stupid” songs—his term—for small-time labels and cutting demos with his Queens College friend Carole Klein (not yet King). Chapter 2 covers the Simon & Garfunkel years, which ended with “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” whose 25 million copies made it, at the time, the music industry’s all-time bestseller. Chapter 3 explores the first phase of Simon’s solo career’s, 1970-1984, when he splendidly disproved the millions of Simon & Garfunkel fans who’d insisted that Simon without Garfunkel would be a bust. Chapter 4 is about Graceland: its making, the swirl of accusations of musical imperialism leveled at Simon, and its tremendous impact and legacy. The final chapter will be about Graceland’s successor, Rhythm of the Saints, which brought Simon to Brazil (provoking further charges of musical tourism), and which he considers Graceland’s equal. We’ll end with a glance ahead at the ups and downs of the immediately subsequent years, including the disastrous failure of Simon’s 1998 Broadway musical, The Capeman. He rebounded from that, too.

As his longtime friend and colleague, the composer Philip Glass, told me in 1993, “Paul Simon is a great artist. Yes—why not? The only music that counts is the music we love, the records in our collection that keep coming to the top. And for a quarter-century now, Paul has generated a tremendous amount of music we love.”

Chapter 1: Pounding Pavement, Paying Dues: 1941-1960

“I have no sentimentality. I move on,” Simon told me with his characteristic deadpan bluntness when we met.

The contents of his airy, high-ceilinged office contradicted him: dozens of mementos, carefully arranged. The Coptic icon from the cover of Graceland. His father’s big stand-up bass (more on Lou Simon in a moment). Tastefully framed photographs: the original cast of Saturday Night Live, whose creator, Lorne Michaels, remains one of Simon’s best friends; the “Jonah Levin Band” from Simon’s flop of a film, One-Trick Pony (Levin, the protagonist, is an over-the-hill folk-rocker: Paul Simon, say, if he’d never had another hit after “The Sound of Silence”). A 1966 contract, for $1,000, for a two-show Simon & Garfunkel concert in Coconut Grove, Florida. Forty gold and platinum records.

Indeed, the whole neighborhood was a memento of Simon’s past. The Brill Building, at 49th and Broadway, overlooks sidewalks he’d pounded more than 40 years before, a nice outerborough Jewish boy chasing a hit. “When Artie and I were fourteen,” he said, “we took the F train in from Queens to audition. You’d walk into some old building, up these creaky, musty stairs, and there was a record company”: Old Town, Apollo, Gone, some fly-by-night, some less so, many of which had helped spawn rock & roll. Just up the street from the Brill Building (which was already past its prime, its heyday the 1930s and ‘40s) was 1650 Broadway, where the action was. As Al Kooper writes in his informative, and very funny Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards: Memoirs of a Rock ‘n’ Roll Survivor, “I’d have to say that the majority of the music business from 1960 to 1965 was at 1650.” Most of it, says Kooper, was in a single company: Aldon Music. During those years, Aldon’s co-owner and prime mover, Don Kirshner, whom Time Magazine dubbed “the Man with the Golden Ear,” saw to it that Aldon became what Kooper called “the hottest song-publishing concern of the early sixties and perhaps of all time.” Sixteen-fifty (and the Brill) were home to far more music publishers, their business the care, feeding, and exploitation of songwriters, than recording studios. Kirshner’s stable of writers, cranking out #1 hits in their soundproofed cubicles, included Carole King, Gerry Goffin, Barry Mann, Cynthia Weil, Neil Sedaka, and Howard Greenfield, a coterie which, as Kooper said, “[had] the top of the charts padlocked.”

In 1958, Paul and Artie, under the goyishe-sounding monikers Tom and Jerry, cut a single, “Hey Schoolgirl,” which made it to #49 on Billboard’s Hot 100 singles chart, not an inconsiderable achievement, and lip-synched it on American Bandstand. No hits followed, and Paul got busy in Broadway’s recording studios, learning the recordmaker’s craft.

“Carole King and I made a lot of demos together—Carole Klein from Brooklyn—for $25 a session. She’d play piano and drums, I played bass and guitar, and we sang all the parts. That’s where I learned how to stack voices and do overdubs—how to make records. One moment, we were making demos; the next, she was making $150,000 a year writing Number One hits. It was”—Simon gave a short, dry laugh—“very demoralizing to me.”

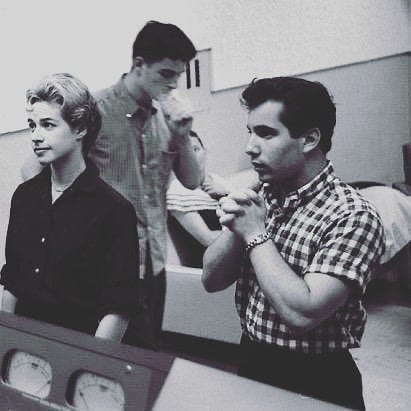

RCA Studios, NYC, 1959. Left to right: a 17-year-old Carole Klein, who’d just switched to “King,” her barely post-teenaged husband and co-writer Gerry Goffin, and P.S., nervously listening to a playback. It was probably an informal demo recording; to my knowledge, Simon and King never released a record commercially. All three of these future millionaires were Queens College students. Simon, a good bokher, graduated; King and Goffin dropped out. The couple were a year away from writing their breakthrough hit, the Shirelles’ “Will You Love Me Tomorrow,” the first #1 song by a Black, all-female group.

Simon’s Tin Pan Alley roots go still deeper. His bass-playing father, Lou (professional name: Lee Simms), not only hired out as a session player, but led a dance band at Roseland Ballroom, on 51st, then 52nd, Street. Lou’s band played Roseland’s Saturday evening and Thursday afternoon radio broadcasts, and when Paul was very little, his parents took him to watch Lou at work. Roseland had strict rules about the styles of music played and dancing permitted, ie. no rock & roll. “Cheek-to-cheek dancing, that’s what this place is all about,” said Louis Brecker, Roseland’s owner. “So I knew a world,” said Simon, “that was pre-rock & roll.”

And not merely dance-band music. The 13-and-14-year-old Paul Simon was in love with another pre-rock sound: the early-to-mid-’50s doo-wop of the Penguins (“Earth Angel”), the Spaniels (“Goodnite, Sweetheart, Goodnite”), and early versions of the Drifters (“Honey Love,” featuring the sensational Clyde McPhatter). All of these groups were Black, and these hits all came in 1954, triggering what was to become Simon’s lifelong love of Black pop music, of whatever nation or region. Nineteen-fifty-four was also the year that Elvis Presley cut his first singles for Memphis-based Sun Records. Elvis hit Simon, as he did the rest of America, like a sledgehammer. The first Presley song that Paul heard, over his parents’ car radio, was “That’s All Right,” Elvis’s debut single. Simon was convinced that the singer was Black. It wasn’t until Elvis’s first, 1956 appearances on national television that an astonished Simon saw that, regardless of how Elvis Presley sounded, he was no African-American.

Was Simon’s discovery nothing more than a sudden, jubilant realization that he, a white kid, could devote his time to singing music spawned by Blacks, music that he so deeply loved? Or is there a more complex, disturbing way to interpret the kid’s epiphany, namely, as a portent of the cultural appropriation of which the Simon of Graceland (or, for that matter, earlier, Black-inflected songs like “Loves Me Like a Rock” or “Take Me to the Mardi Gras”) would be accused? Did Simon’s greatest album prove that he was, as I paraphrased critics of Graceland in my Life piece, “a predator, a musical imperialist… a millionaire singer [who] profited from the music of Black South Africans”? Although Simon has articulately defended his use, as it were, of his Graceland collaborators’ music dozens, if not hundreds of times, the question remains unanswered.

The rarely heard “Dancin’ Wild,” the flip side to “Hey Schoolgirl.” Tom and Jerry had surnames, as per the label; Artie was “Tommy Graph,” Paul “Jerry Landis.” The duo were, well, shameless Everly Brothers imitators, and when the Everlys ran out of hits to clone, Paul and Artie parted ways (Breakup #1 of many). Simon needed a new direction, and left for England, where he honed his folk-music skills and wrote a number of Simon and Garfunkel’s early songs.

Tom and Jerry, 1957

(Note: the first half-dozen seconds of the audio segment below are faint. The volume picks up thereafter).

Looking forward to the next installment!

Me too!