Mr Cooder, Mr Gibbons, and Mr Johnson

Part Two of what will be an ongoing series on Robert Johnson: the audio of two extensive interviews with Ry Cooder and ZZ Top's Billy Gibbons, an authentic (was that eccentric?) guitar hero himself

Last October I posted about one third—less than that, now that you mention it—of the transcript of an extended interview I conducted with Ry Cooder in the fall of 1991, on the eve of a long-awaited album. Rarely, in fact (outside of the Beyoncé/Taylor Swift cosmos) has a record been as eagerly awaited, and for decades, as the two-CD set Robert Johnson: The Complete Recordings: 29 songs and 12 outtakes by the genius of the Mississippi Delta blues, dead—probably murdered—at 27, in 1938. Bated-breath anticipation of a handful songs recorded by someone who’s been dead for 85 years—outside of your Enrico Carusos, this was unusual.

Apart from Cooder, I spoke to a dozen rock stars for a cover story for Musician, where I then worked, about Johnson’s impact on their music, including Robbie Robertson, Robert Plant, Billy Gibbons, and the late Memphis producer Jim Dickinson (another reporter interviewed Eric Clapton and Keith Richards).

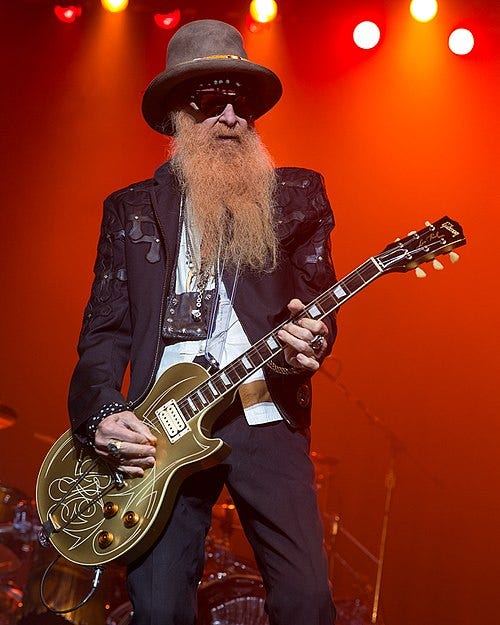

A gifted blues-rock guitarist and a Johnson devotee since age 14—curiously, the age at which many Johnson enthusiasts, myself included, discovered the Columbia LP King of the Delta Blues Singers, sixteen Johnson songs plucked from oblivion in 1961 by the great record man John Hammond—Billy Gibbons was not only eager to hear the Johnson box, but confident that it was going to take off commercially. "Just wait,” he said. “This thing is going to be in BMWs all across America. It’s gonna be the hippest thing money can buy." He was right. Robert Johnson: The Complete Recordings, went platinum, selling more than a million copies.

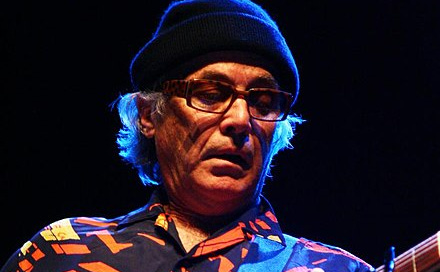

Two guitar heroes named Cooder (above) and Gibbons (below) give in-depth interviews, below, on Robert Johnson, a mutual icon.

Ry Cooder, himself brushed by genius, has thought harder about Johnson, and with greater acuity, than probably any other musician. Cooder’s insights put those of most, if not all, musicologists to shame. Here is the unedited audio of our 1990 interview, full of surprising insights, the product of the hundreds of hours that Cooder has spent listening to, pondering, and playing Johnson’s music. Yet Cooder, curious, probing, and impatient by nature, remains frustrated, and always will, because we’re never going to know more than a few facts about Johnson. We don’t know who killed him, nor where his travels took him, nor very much about the music he played outside of the recording studio. “We don’t know nothing about this poor damn guy,” Cooder told me, his frustration palpable.

Unlike Cooder, Gibbons, whose 30-plus-minute interview, lightly edited, immediately follows Cooder’s, is not uncomfortable with, but welcomes, the mystery that will always cling to Johnson. Yet both were delighted—and, as guitarists, relieved—when the two famous photographs (now there are three) were made public in the mid-to-late ‘80s.

What especially fascinates Gibbons is Johnson’s remarkable hands. “I’ve joined the many,” he said, “that are fascinated by his hands. They’re spiderlike. Now, to try and perform Robert Johnson compositions is a difficult task, and I’m not convinced that anyone has successfully done so. And to behold those hands is reassuring; it’s a relief to those of us that are totally mystified by this guy and his playing. Just looking at his hands—they’re a thing of beauty. And they go with what you hear.”

Nor can Cooder get over those hands. “You see the photographs,” Cooder said, “and after all the speculation and ponderings, you say, ‘Oh, okay, I see this guy. This is an out-front, wide-open-faced, aggressive-looking guy. With strange hands.’ I’ve never seen hands like that, jointed at the top like that; it’s the goddamndest thing I’ve seen. But he had to be strange physically to do what he did. I’m telling you, it is very hard to do. I can’t play like him. I can play around him, in the neighborhood. But I can’t get in the door.”

Below: Three views of Robert Johnson, the only ones known to the public. A fourth exists, in the vaults of the Smithsonian Institution; I have zero idea when, or if, the curators will make it public.

And here are the Cooder and Gibbons interviews. Enjoy them.

I may have said this, but quite apart from his musical gift, he's one of the smartest people I know. He's 76; I hope he stays with us for a long time yet

Looking forward to carving out time to listen to this. Thanks for sharing!